Part One: Violence Reigns

Part Three: Splintered Shards of Time’s Reflection

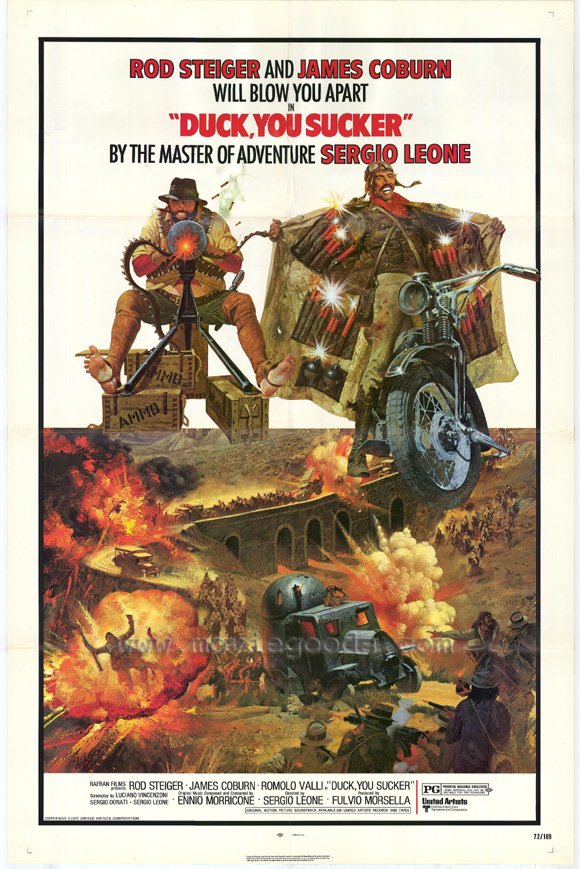

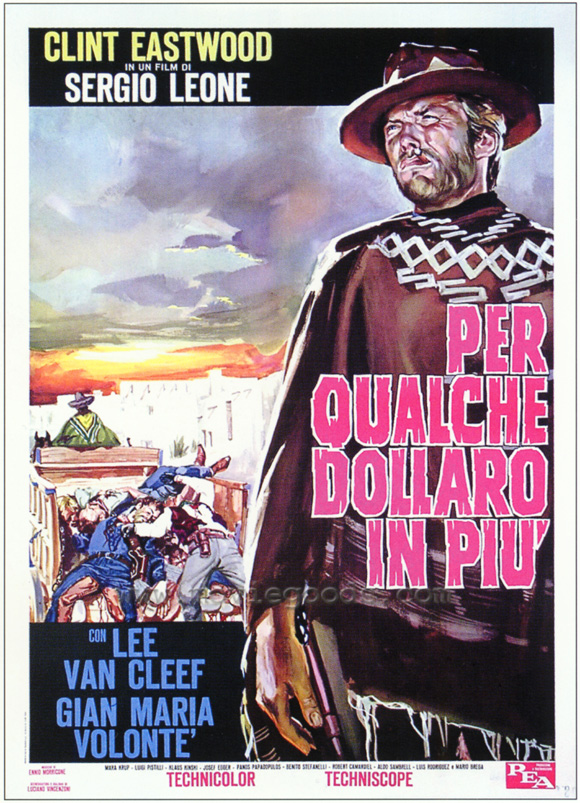

For a Few Dollars More is the second film in Leone’s Dollars or “Man with No Name” trilogy and the only one equipped with an epigraph: “Where life had no value, death, sometimes, had its price. That is why the bounty killers appeared.”

They also appear in Wagner’s “Raven’s Eyrie,” the basic situation of which — “ruthless, half-wild outlaws hounded by killers as remorseless as themselves” — recalls For a Few Dollars More, as does the disclosure that “The Combine cities of Lartroxia’s coastal plain had set a high bounty on Kane, and Pleddis meant to claim it.” Colonel Mortimer in the Leone film is out to avenge his sister, who killed herself while being raped by Indio; Ionor, raped by Kane seven years before the events of “Raven’s Eyrie,” does not kill herself but only her maternal instincts while scheming to be her own Mortimer. If Kane seems to be cast in the Indio role in “Raven’s Eyrie,” he behaves like the No Name of For A Few Dollars More in “Sing a Last Song of Valdese,” intervening at the moment of truth to secure another man’s vengeance for a rape and murder. As Leone once said, “An assassin can display a sublime altruism while a good man can kill with total indifference.”

Bounty killers presuppose the existence of men on whom a bounty can be collected, and due to costuming and casting constraints and perhaps a venerable European susceptibility to New World noble savages, spaghetti Westerns tended to ignore Indians and the skirmishing associated with John Ford’s cavalry films in favor of bandits by the dozens and hundreds. Wagner’s repertory company is also chockablock with desperados. In “Sing a Last Song of Valdese” we meet Mad Hef, who is by no means resigned to his capture by Ranvyas the ranger: “There was other smart bastards all set to count their bounty money, but ain’t one of them lived to touch a coin of it.” Hechon in Bloodstone doesn’t know enough to get out of Kane’s way, and Grey’s bandits in “Lynortis Reprise” are particularly Leone-esque: “A circle of grinning wolfish faces, casually moving in across the space of washed stone and dry bones.”

Orted ak-Ceddi in Dark Crusade could be straight from an Italian Western — “for all his pose as a popular hero and champion of the downtrodden, Orted the bandit chieftain had been a ruthless outlaw who left a wake of murder and rapine wherever his band passed through” — and just as Indio’s dependence on marijuana was a departure for a Western in 1965, Wagner’s matter-of-factness about “the tingling rush of cocaine” after Orted has “snorted, sneezed, [and] swallowed” marked an arrival: sword-and-sorcery had caught up with the Seventies.

(Continue reading this post)