This, That, T’Other

Tuesday, September 16, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Haterade drinkers insofar as “The Black Stranger” is concerned often target the character of Tina for special opprobrium, condemning in particular the punishment Valenso frantically administers to her as a distasteful piece of Brundage-bait, Howard blatantly angling for another Weird Tales cover or at least catering to a one-handed segment of his readership. Paying attention to the way the scene is constructed and described should be enough to disprove such allegations, but turning to “The Black Stranger: Synopsis A” in The Conquering Sword of Conan is also useful in that the synopsis is of course Howard selling Howard on his latest idea, telling the story to himself, engaging in the equivalent of a filmmaker’s “pre-viz” (previsualization). Here he refers to Tina as “a flaxen-haired Ophirean waif,” “the little Ophirean girl,” and “the child,” and Valenso loses the self-control that should be a Zingaran grandee’s watchword as follows:

The nobleman instantly seemed seized with madness, and had the girl cruelly whipped, until he saw she was telling the truth.

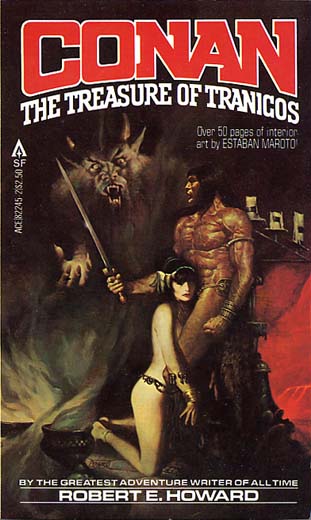

Nary a hint of a prurient agenda. I sometimes wonder whether Esteban Maroto contributed to the muddying of the waters here; his illustrations for the 1980 Ace standalone The Treasure of Tranicos leer at Tina through a vaseline-smeared lens as a pillowy, pouty houri on the brink of several Sapphic interludes with Belesa:

Even in the drawing depicting what REH intended to register as child abuse she looks ready to be photographed by Suze Randall. One wonders what Mr. de Camp thought (other than Ka-ching! — it would of course take another seven years for Howard’s “The Black Stranger” to dethrone its usurper).

Aside from the objections to the scene where the whip comes down, we’ve been treated to arguments that a child has no business being in a Conan story. For starters, doesn’t it seem as if heroic fantasy that features the, or a, human race should make room as needed for the younger members of that race? Also, I regard Tina as a logical follow-on to the inclusion of Zelata in The Hour of the Dragon; they’re both “tetched in the haid” clairvoyants who represent expansions of Howard’s character demographics. And the Ophirean waif’s significance just cannot be understood without being familiar with the role of Pearl in The Scarlet Letter. If that contention comes across as snobby or pretentious, c’est la guerre culturelle. Even if we discount Tina’s insight-all-her-own into both the story’s “black man” and Conan himself, the seeing of the hero and the monstrous forces he or she opposes through eyes other than those of an omniscient narrator is an essential sword-and-sorcery technique. Although not herself a POV character, Tina is a character who memorably shares her POV, to the enrichment of “The Black Stranger.” Like Bergil in The Return of the King or Klesst in “Raven’s Eyrie,” Howard’s child earns her place in the story (and my guess is the precedent of Tina was the permission slip KEW needed to create Klesst).

Over at this site’s dog-brother Morgan Holmes commissioned an analysis of L. Sprague de Camp’s 1980 Conan and the Spider God from one-time REHupan Richard Toogood. We can but pray that the latter was in a position to supply his own HazMat suit, as the Tartarean godawfulness of Spider God inspires the suspicion that Lin Carter was carrying de Camp all those years.

Seriously, the mere fact that its author was willing to publish this nithing-novel under his own name should have been enough to cause each and every copy of Literary Swordsmen & Sorcerers anywhere in the world to burst into eldritch green flames or leak ichor. Spider God is so disgraceful a performance that Sigurd of Vanaheim would have been enraged into behaving like a real Vanirman had he been forced to read it.

Although lacking the artistry and eschewing the quotage-with-malice-aforethought of Twain’s “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses,” Toogood’s indictment is at least as methodical; one of de Camp’s Still Starry-Eyed After All These Years faithful could only manage the rubber-bladed non-riposte “Let’s see Morgan write a Conan novel.” For my part while admiring Toogood’s unflagging capacity for outrage, I’m inclined to quarrel with one of his assertions:

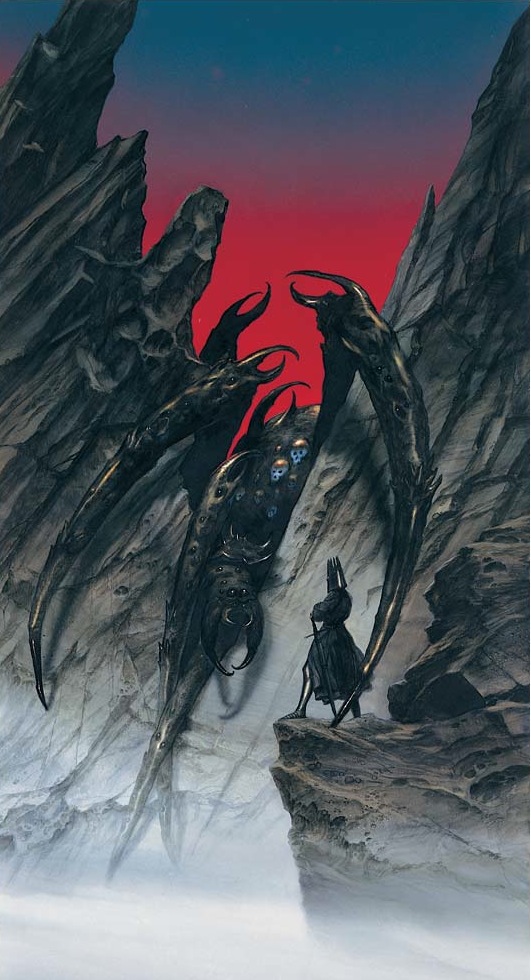

At the risk of appearing chauvinist, I would also suggest that the use of a spider as a central feature indicates the governing hand of a woman in the creation of the book. Spiders are far more of a female fear than a male one as a thousand cartoons and sit-com clichés will testify to.

To which I would retort: Lord Dunsany. H. G. Wells. Robert E. Howard. Clark Ashton Smith. J. R. R. Tolkien. Stephen King. China Miéville.

A few weeks back I was reproached for omitting up-and-comer Joe Abercrombie from my survey of sword-and-sorcery since the Eighties. The shameful truth is, I’d never heard of Abercrombie or his three novels when I drafted the article, but I’m now scrambling to make up for lost time. In the interim, here’s a passage of interest from his appreciation of George R. R. Martin’s epochal/epic A Game of Thrones:

Way back in the ’30s Robert E. Howard’s Conan had been dark, dense, and muscular with a sprinkling of kinky. In the ’50s Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser had been dark, dashing and greasy with a faint aroma of gutter trash. In the ’70s, Michael Moorcock’s Elric and Corum had done away with light and dark altogether and replaced it with something much weirder and more thought-provoking. With A Game of Thrones, Martin dialled the dark up higher than ever before, but the thing that he really brought to the party — and it may seem a strange thing for a fantasy book — was realism.

“Sprinkling of kinky” — there’s the flagellation again. And I think the clearly-intended-as-compliments “greasy” and “aroma of gutter trash” in connection with Leiber are evidence of a perceptive, keen-nostrilled reader.

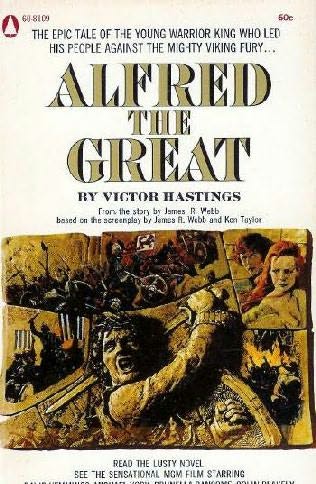

Lastly, and the segue can’t help but be graceless, David Foster Wallace’s writing was mostly outside our bailiwick here, but the news that he hanged himself at the age of 46 this past weekend, like the suicide of Thomas M. Disch on July 4 of this year, was enough to get the oldest and least curable of Howardist-wounds weeping a little. Much of Wallace’s work was on the to-do list for me but I revered Disch’s, from his early classics The Genocides (1965), Camp Concentration (1968), and 334 (1974) through his laser-seared book reviews for T. E. D. Klein’s Twilight Zone Magazine and his genre-dipped-in-liquid-nitrogen sequence The Business Man: A Tale of Terror (1984), The M. D.: A Horror Story (1991), The Priest: A Gothic Romance (1994), and The Sub: A Study in Witchcraft (1999). And it’s always been a source of delight that he wrote not only a Prisoner novel but also served a shield-wall stint by novelizing (as “Victor Hastings”) the 1969 film Alfred the Great:

Back in 2000 I did devour Wallace’s “McCain’s Promise: Aboard the Straight Talk Express With John McCain and a Whole Bunch of Actual Reporters, Thinking About Hope,” republished this year for obvious if (for some of us) melancholia-tinged reasons. He certainly had a knack for memorable titles — Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again — and the critic Sven Birkerts singled out his “Pynchonian celebration of the renegade spirit in a world gone flat as a circuit board.” As Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow is one of the novels that most aided me in making sense of the 20th century’s non-sense, I knew I had an eventual date with destiny in the eidolon-esque form of Wallace’s 1,079-pager Infinite Jest, but now that reading experience will be…different.

I’m skeptical about suicide explanations that lean overmuch on chemistry or casuistry, and ever since an introductory German course have preferred that language’s word Selbstmord (“self-murder”) as being more brutally direct in capturing the enormity of the concept.. It was dispiriting to notice that within hours of the first news item in the Los Angeles Times someone predictably posted “What a selfish, cowardly idiot. Just another self-centered fool who thought of no one but himself” in the comments space. Me, I tend to look upon suicide not as sin or statement but as a Black Colossus of a decision; it’s one thing to determine that the accommodations are not to one’s liking but another altogether to insist so emphatically that only one exit from those accommodations is available. Recalling the words of Eastwood’s William Munny in Unforgiven –“It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man. You take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have” — they apply just as much when the trigger is pulled with the gun pointed inward. The suicides of gifted writers like Disch and Wallace (and Howard before them) are not intrinsically more tragic than those of anyone else, but I don’t think it’s insensitive or unfair to posit a particular pang or subcategory of loss when creators who have it within them to usher us to worlds we would otherwise never visit instead usher themselves out of the world we share.