Something to Do With Deathlessness, Part One: Violence Reigns

Friday, September 12, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Part Two: Eyes We Dare Not Meet in Dreams

Part Three: Splintered Shards of Time’s Reflection

[On October 13 it will have been 14 years since we lost Karl Edward Wagner. On April 30, 2009 we will have had to do without Sergio Leone for 20 years. These are wounds that don’t heal, absences that are always present, and what follows is an attempt to honor both men by way of a two-great-tastes-that-taste-great-together approach]

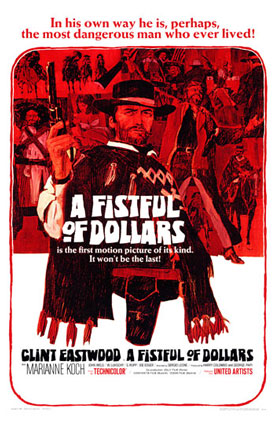

In his own way he is, perhaps, the most dangerous man who ever lived!

(From the United Artists advertising campaign for the 1967 American release of A Fistful of Dollars)

Once upon a time, two genres got the troublemakers and Maker-troublers they deserved. What Sergio Leone did with — and to — the Western, Karl Edward Wagner did with and to modern heroic fantasy. Both men toyed with clichés and conventions cat-and-mouse–style, and both subjected the phatic discourse of the retread and the rehash to brutal interrogations. Neither, however, was simply a revisionist. Leone and Wagner came not to revise but to revive, and where the revisionist impulse often expresses itself in harangues, they favored the parable and silver-scalpeled illusionectomies.

Nor were the two men iconoclasts, except insofar as iconoclasm involves smashing existing sculptures and thus yields detritus from which even larger and more mythic figures can be fashioned. Christopher Frayling, the author of Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys & Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone and Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death, draws a crucial distinction by describing Leone’s “melodramatic expressionism” as “an act of demythologisation, rather than demythicisation.” Wagner’s Kane and Leone’s pistoleros are liberated from ossified mythologies while suffering no shrinkage in stature. Their mischief-making remains mythic in both reach and grasp, and their anarchic activities cannot be plea-bargained down to hero’s journeys.

If both men broke rules as blithely as stuntmen break glass, it is because they were outside agitators in the best sense. Leone, an Italian trespassing or claim-jumping in the most American of genres, admitted as much while making a biblical allusion that is not without interest to students of Karl Edward Wagner:

The Americans have the horrible habit, among other habits, of diluting the wine of their mythical ideas with the water of the American way of life. . .A world without conflict, Abel without Cain. Hygiene and optimism are the woodworms which destroy American wood. It is a great shame if “America” is always to be left to the Americans.

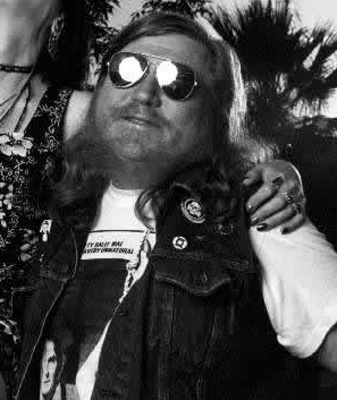

Wagner was of course an American, but too reflective to have been reflexively all-American. Although outgoing, he also seems to have been out-dwelling, a man destined for detachment, as indicated by his final interview, conducted by Bradley Sinor in 1994:

I grew up [in Knoxville], survived high school and the 1950s, but never became part of the local culture. In 1967 I graduated from Kenyon College with an A.B. in history, but never became part of the local culture. I then moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina to attend medical school at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. I went for a combined MD/PhD (neurobiology), but never became part of the culture and dropped out for a few years to become a Haight-Ashbury hippie and to write.

He was not easily absorbed, except by his reading, which resulted in an erudition remembered by Peter Straub in Exorcisms and Ecstasies as “extraordinarily profound and precise.” Straub adds that that Wagner “did everyone the favor of sharing what he knew about the European variants of horror’s tropes.” Just as the commedia dell’arte and Sicilian puppetry are discernible in Leone’s Westerns, many Old World trace elements appear in the Kane stories. It is only fitting that a supposed distant relative of Richard Wagner’s should write of a ring more ill-omened than that of the Nibelungs in Bloodstone or invoke another Rhine legend by asking How many times, Dessylyn, have you played at Lorelei? in “Undertow.”

Philip French terms the Western “a great grab-bag, a hungry cuckoo of a genre, a voracious bastard of a form equally open to visionaries and opportunists” in his survey Westerns: Aspects of a Movie Genre. Sword-and-sorcery also boasts the dubious pedigree but indubitable vitality of a mongrel; in Wizardry and Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy, Michael Moorcock speaks of a “mélange of influences [that] was scarcely digested before [Robert E.] Howard was, as it were, pouring it back on to the page.” Michael Swanwick’s 1994 essay “In the Tradition. . .” imagines several types of fantasy benefiting from dead-of-night deals effected by “ridge-runners and embargo-breakers smuggling influences. . .across the borders,” and both Leone and Wagner enriched their work through such illicit commerce.

Had it been completed, Wagner’s novel Satan’s Gun would have been a denizen of the borderland between the Western and dark fantasy inhabited by Joe R. Lansdale’s Dead in the West, Nancy Collins’ Dead Man’s Hand, David Gemmell’s Jerusalem Man novels, and Stephen King’s Wizard and Glass. Introducing the fragment that we do have, Wagner stated that his heroes had “always been cowboys. . .correction, Willie — gunslingers,” and when speaking to Dr. Jeffrey Elliot in 1981 touched upon the fact that “A lot of people say that heroic fantasy is the Western of the science fiction/fantasy field” before distancing himself from hackwork in either genre:

Good guys in white hats, bad guys in black hats, with a shootout at the end. Everything’s swell, the farmer’s daughter is rescued, and the hero rides out of town, looking for new adventures. There are probably some fantasy writers who write like that. Kane is more like what Sam Peckinpah might have in mind.

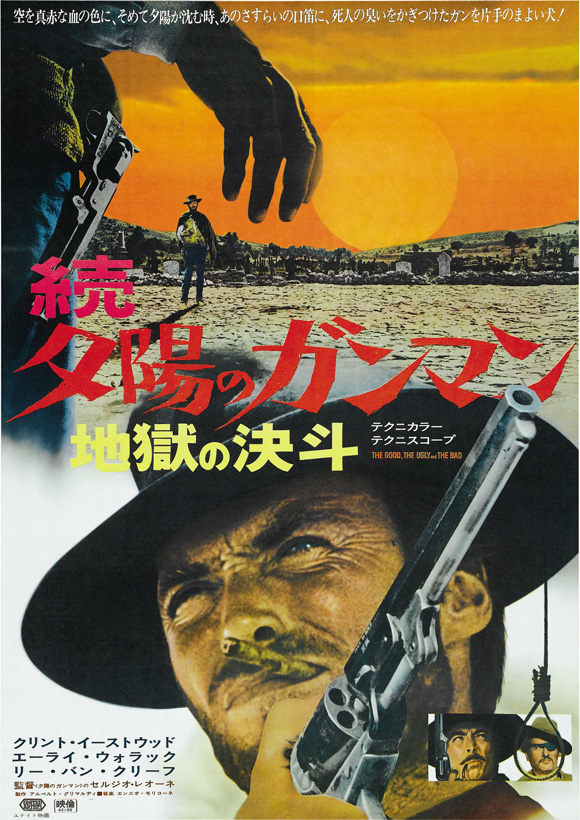

Whether or not Leone influenced Peckinpah is a matter of dispute, but he certainly emboldened and ran interference for the American director. His impact on Wagner, however, is indisputable; Kane’s creator told Bradley H. Sinor that “Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars brought home the fascination for the amoral wandering killer.”* But Wagner got more than just mystery and mystique from Leone; he was struck by a directorial vision that was just that, a way of seeing both authoritative and authored, and admitted “I am fond of Sergio Leone. I conceive of my story through visual patterns, and for this reason I’m probably more influenced by cinematic techniques than by literary.”

Interviewed by Cenk Kiral in 1998, screenwriter Luciano Vincenzoni said of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly that “Leone wrote the film with a camera.” As we shall see, Wagner tried to film his heroic fantasy with a typewriter. Leone is the tutelary deity when Adrian Becker makes his entrance in the “Satan’s Gun” fragment:

Under the shadow of his slouched cavalry hat, the stranger’s eyes were grey — a faded blue that seemed impersonal, yet savagely alert.

An unmistakably European gunfighter, Becker might call to mind the grimy paladins played by Franco Nero and Jean-Louis Trintignant in Sergio Corbucci’s Django and The Great Silence rather than The Man with No Name were it not for the long shadow that For a Few Dollars More casts over the fragment. Both feature a character known as The Prophet, and both involve madmen who are liberated from confinement in a “tumult of gunfire and death.” Just as No Name confronts the gambler “Baby” Red Cavanagh and, when asked what the stakes are, replies “Your life” before gunning down Cavanagh and three allies, Becker exposes cardshark Alonso Squires, agrees “That’s the stakes” when the other man exclaims “That’s killing talk!” and then blasts Squires and three cronies who intervene.

Yes, Wagner knew his Leone films. Unfortunately, Adrian Becker is only available to us in the tantalizing “Satan’s Gun” and two stories of vignette-ish brevity, “Hell’s Creek” and “One Paris Night.” Pausing long enough to note that Becker kills Squires & Company in a town called. . .Genesis, we must turn to the German’s great-grandsire Kane if we are serious about studying similarities between these artists.

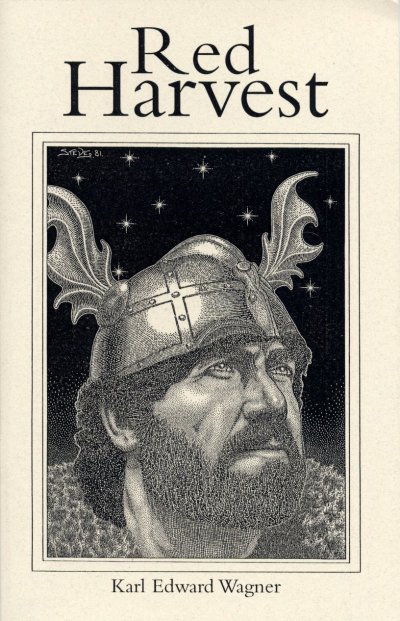

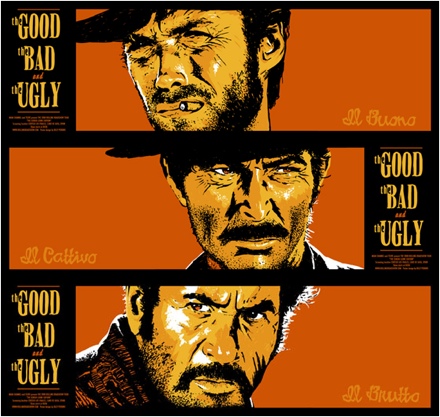

The Kane novels Bloodstone, Dark Crusade and Darkness Weaves and the Kane stories collected in Death Angel’s Shadow, Night Winds and The Book of Kane share with Leone’s films many of the “seamless contradictions” identified by Richard Corliss in his Cinema: A Critical Dictionary entry for the Italian director. Corliss lists “labyrinthine plots and elemental themes, nihilistic heroes with romantic obsessions, microcosmic close-ups and macrocosmic vistas. . . playful parody and profound homage.” Playfulness and profundity team up when we recognize that the designation “larger than life” belittles The Man with No Name and Harmonica and their adversaries as it does Kane and his enemies. From the harrowing of hell to a red harvest (the title of a chapter in Dark Crusade) in Hammett’s Poisonville or Leone’s San Miguel is not far as the myth flies; the Italian referred to Clint Eastwood’s No Name in A Fistful of Dollars as “an incarnation of the angel Gabriel,” and Kane for his part is a veteran of at least one war in, or on, Heaven.

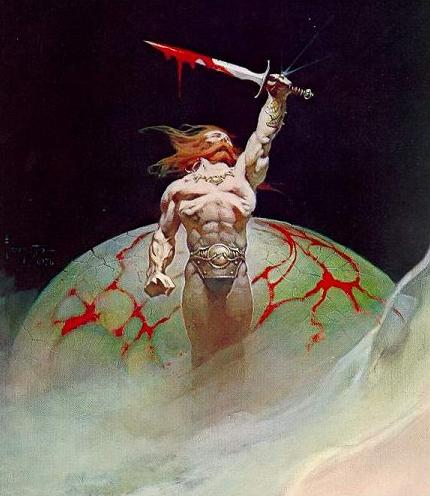

Much of the writing about Leone ventures outside genre boundaries in an effort to convey the look and feel of his Westerns. Daniel Edwards conjures up “a mythical landscape where a man could reach beyond the pall of civilization to a fantastical space where enrichment depended on one’s skill with a gun and ability to deceive an opponent.” Robert C. Cumbow reminds us that Leone “gained a foothold in cinema through Biblical spectaculars and the ‘sword and sandal’ mythological epics” before speculating that Harmonica and Frank in Once Upon a Time in the West “represent a privileged race of supermen who stand to normal men — morally and historically — as Titans to Olympians: they are older, tougher, simpler, less flexible, and doomed.” Wagner’s Kane is of course an escapee from the Book of Genesis, and Leone’s wandering killers are rather like Nephilim, only distinguishable not so much by their size and strength as by their speed and skill.

For Christopher Frayling “Leone is less interested in the opening of a new frontier than in the closing of a more ‘ancient’ one.”* That terminus is Homeric, and the epic scale and scope can induce agoraphobia, as Mary Corliss pointed out in a 1984 article:

The West for Leone was so big and empty, only giants could fill it. . .With hardly anybody else alive, as if most forms of life had been wiped out in some 19th-century apocalypse, the survivors were deciding at gunpoint which of them would get to create a new species in his image.

Similar imagery is easy enough to locate in Wagner’s heroic fantasy. He informs us in Bloodstone that “The Southern Lands [stand] along the frontier of mankind’s emerging civilization,” while in “Two Suns Setting” that same frontier runs right down the middle of Kane and Dwasslir’s debate about whether man is a legitimate heir to greatness or just a squatter.

In his Sergio Leone: The Great Italian Dream of Legendary America, Oreste De Fornari comments “the desert dust confounds the uniforms and perhaps the centuries as well” in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Henry Fonda’s Frank is forced to admit that he is no businessman in Once Upon a Time in the West, “just a man.” To which Charles Bronson’s Harmonica appends “An ancient race,” surely gnomic were we to confine ourselves to a Western frame of reference. Similarly, the Roman arch foregrounded against the backdrop of Monument Valley in the film’s climactic flashback intrudes from a non-native antiquity; as Robert C. Cumbow stresses it lacks “visible relation to any buildings or to any world beyond that desolate place.” Like a painted Dali or de Chirico dream, the arch suggests a ruin or relic from an old order, some archeologist-evading, all-but-vanished empire, as does the long view taken by the bandit Juan Miranda in Duck, You Sucker. While robbing one of the moneybags who sneer at him at close quarters in a stagecoach, Juan reveals “My mother, she had the blood of the Aztecs, which was before your people.”

In remarks that he made to the magazine American Film, Leone sounds more like a Tolkien, a Howard, or a Wagner than a man who told stories about gunslingers and gangsters:

The important thing is to make a different world. To make a world that is not now. A real world, a genuine world, but one that allows myth to live. The myth is everything.

To make that different world, Leone always wanted more time, and also more Time, more than the Western as a historically circumscribed genre could give him. He needed the dateless depths of prehistory and myth, the same depths that are the playground of modern heroic fantasy. Critic Richard T. Jameson said of Once Upon a Time in the West that “there is never less than a world at stake in any moment of the film,” and that holds true for the Kane stories as well.

And the worlds at stake? They have a great deal in common. Neither is much peopled; Wagner once captioned a photo of himself “Shortly after 1970 our world ended and with it any hope for intelligent life on Earth.” Such denizens as remain are mostly predators and those less skilled predators who become prey. In Spaghetti Westerns Christopher Frayling quotes Leone on what sets him apart from John Ford: “His characters and protagonists always look forward to a rosy, fruitful future. Whereas I see the history of the West as really the reign of violence by violence.”

Echoing that characterization, Laurence Staig and Tony Williams could be commenting on “Misericorde” or Darkness Weaves or “Sing a Last Song of Valdese” or The Road of Kings as well as Leone’s films in their Italian Western: The Opera of Violence: “. . .an insecure environment of grotesqueness abounding in almost surrealistic dimensions, in which Violence reigns.” One of the blackest jokes in Wagner’s Dark Crusade is that when the Sataki zealots look to midwife “a world reborn in darkness,” they are being redundant.

In Leone’s films and Wagner’s stories violence underlies, precedes, or replaces all other forms of human interaction. Its prevalence does not indicate a failure of imagination on the part of director or writer but rather paroxysms and prodigies of imagination. Anthony Mann, a precursor of Leone in some ways, objected to comparisons: “The characters of For a Few Dollars More meet along their road only the “black” of life. The bad ones.” To which Wagner, in “a fragment attributed to Opyros,” devised a retort as applicable to Leone’s work as to his own:

The colors of darkness are no monotonous hue —

For the blackness of Evil knows various shades,

Full many as Evil has names.

Both men set themselves the task of asking and answering the pessimist’s definitive question: What’s the worst that could happen? Leone labeled himself “a Roman, therefore fatalistic and pessimistic.” Wagner referred to the “pessimistic, violent concept of existence in a hostile universe” that he shared with Robert E. Howard.

Christopher Frayling stresses Leone’s “detached calm” while observing his characters’ brutal behavior: “They are brutal because of the environment in which they exist, and they make no attempt to change that environment.” When a Wagner character — Gaethaa, known as the Crusader, the Good, and the Avenger — does attempt to change such an environment in “Cold Light,” we are presented with a cure that’s even worse than the disease in that it is hyperactive and hypocritical:

He was a fanatic in the cause of good, and once he had recognized a center of evil, he trampled over every obstacle that would hinder him from burning it clean.

Leone’s killers roam appropriately pitiless terrain; as Frayling writes, “the parched desert provides a suitable backdrop for a world based on brutality, apathy, and callousness.” In “Two Suns Setting,” a Kane story that begins with the utterly Western trope of approaching a stranger’s campfire, the Herratlonai, “a land that even ghosts have abandoned,” is “unearthly in its chill desolation.” Wagner offers more variegated landscapes than does Leone; no equivalent to the autumnal authenticity of the mountain settings of “Raven’s Eyrie” and “Sing a Last Song of Valdese” can be found in the Italian’s filmography. But Kane’s world is, like Leone’s West in the words of Lee Clark Mitchell, usually “an empty arena for haphazard violation and death.” “The Other One” finds the hero-villain recounting the events that ended in “an expanse of total annihilation — a wasteland of toppled stone and fire-scarred rubble.” A courtyard in “The Dark Muse” is “a squalid wilderness of refuse dumps, small vegetable plots, and animal pens,” while the prologue of “Lynortis Reprise” limns a “silent wilderness of desolation.” Beaches in Dark Crusade are choked with refugees and their attendant “miasma of sweat and refuse and filth and fear.” The time is out of joint — all times are out of joint:

It was an age of near anarchy, when a man might take whatever he could hold, and force of might overruled all laws temporal, spiritual, or natural. (Dark Crusade)

Beyond the security of city walls, Chrosanthe was a lawless wilderness, ravaged by the private armies of the powerful lords and plundered by marauding bands of outlaws. Often the distinction was of little consequence, if it could be drawn at all: the Vareishei were a case in point. (“Misericorde”

And the “security of city walls” serves only to enclose victimizers and victims, whether the city be Carsultyal, man’s first, in Wagner’s “Undertow,” or New York, the emblematic modern megalopolis, in Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America. Peter Bogdanovich, who fell out with the Italian after being considered to direct Duck, You Sucker, complains in Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death that “in Leone’s pictures, there is no future; it’s just killing.” That isn’t quite accurate; for Leone and Wagner killing, or the less heroic murder, will dominate the future just as it has reddened our past.

Writing about No Name, Vincent Canby of the New York Times termed him “the perfect physical specter haunting a world in which the evil was as commonplace as it was unrelenting.” The only refuge available in such a world is not in morality but superior skill; Leone correctly claimed to have “introduced a hero. . .who was totally at home with the violence which surrounded him.” Asked if he really has no use for peace by Ramon Rojo in A Fistful of Dollars, No Name counters that “It’s not real easy to like something you know nothing about.”

Kane’s dissatisfaction with the peace enjoyed by the creator’s chattels in Eden goads him not only to invent murder but remain the most inventive of murderers; as Efrel’s demon informant concludes in Darkness Weaves, “Violence and death are the proper element of this lord of chaos, and herein he is master.”

In his 1994 Clint Eastwood: Filmmaker and Star Edward Gallafent says of No Name that “his commitment is only to himself, to a concept that he has of himself.” That concept manifests itself in a sardonic awareness both lucid and ludic. No Name and Kane instigate and orchestrate conflict and do so sportively; if violence is pandemic, they are often its stylish vectors. But there are morbid as well as mordant aspects to the characters, what Gallafent calls “the quality of the isolation conferred by closeness to violence and death.”

Arriving in San Miguel at the start of A Fistful of Dollars, No Name is welcomed by a dead man on horseback who would tell a tale even without the sign around his neck that reads “Adios Amigo.” Soon the American mercenary is placing advance orders with the undertaker and discoursing on the usefulness of the dead, two of whom he passes off as the supposed survivors of a massacre hiding out in a graveyard. “You look as though this place suits you very well,” Silvanito tells him as they stand among the tombstones. He escapes a coffin all his own by escaping in a coffin, and puts his own spin on Ramon’s dictum that “when a man with a .45 meets a man with a rifle, the man with a .45 is a dead man.” Surveying the town of Agua Caliente in For a Few Dollars More, Gian Maria Volontè’s Indio observes “It looks just like a morgue. . .and it could be one so easily.” By the end of the film a bounty killer’s bonanza awaits No Name; like Ares in the Aeschylean metaphor, he is “a gold broker of corpses.” The triangular gunfight at the end of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly takes place at the center of Sad Hill Cemetery, and Angel Eyes goes into the ground before the Confederate gold comes out of it. In Once Upon a Time in the West Harmonica is all past and no future; when Frank demands to know who he is, he only gives the names of dead men, Frank’s victims. Cheyenne warns Jill away from the Charles Bronson character with the most famous two lines of dialogue from any Leone film: “People like that have something inside. Something to do with death.”

As does Kane, whose blue eyes are even more expressive than Harmonica’s:

Insensate craving to kill and destroy — consuming hatred of life. With such eyes would Death receive the newly dead, or Lord Tloluvin welcome some hideously damned soul to his realm of eternal darkness.

In Darkness Weaves those eyes are to be met in a lair Gothic enough to make Monk Lewis beg for a nightlight; Kane occupies an “ancient shadow-haunted burial chamber” in the cliffs behind the city of Nostoblet. His tombmates are the skeletons he has evicted from the coffins he chops up for firewood, and his neighbors are marrow-minded ghouls. Dark Crusade finds him brooding over a battlefield where he is not a Chooser of the Slain but rather their user: “The rising breeze moaned a ghost-song through the waving grassland, and its death-scented breath fanned his billowing red cloak.”

Another story, “Undertow,” eclipses even the standard Wagnerian blackness by beginning in a necrotorium and ending with a man whose rude awakening entails the discovery that he has eloped with a corpse. Kane himself wakes up in “Mirage” not with but very nearly as a cadaver:

Kane decided that he must be in the family crypt that lay beneath Altbur Keep, for in the gloom he could discern the cobweb-hung shapes of other stone coffins, some reposing in niches of the wall, others set like his upon pedestals above the floor. With an effort Kane hoisted himself out from the confines of his sarcophagus and fell to the floor.

Some of the places to which No Name and Kane travel are so moribund as to render their murderous errands coals-to-Newcastle undertakings. Lee Clark Mitchell has this to say about the setting of A Fistful of Dollars in his Westerns: Making the Man in Fiction and Film:

From the beginning, San Miguel is conceived allegorically, as a cityscape of death where even women are professedly not women but “only widows.” Silvanito complains that “we spend our time here between funerals and burials,” eliciting from No Name the dry confirmation that he “never saw a town as dead as this one.”

Wagner enshrouds an entire kingdom in “Cold Light”:

Demornte where death has lain and life will no more linger. Land of death where only shadows move in empty cities, where the living are but a handful to the countless dead. Demornte where ghosts stalk silent streets in step with the living, where the living walk side by side with their ghosts. And a man must look closely to tell one from the other.

Demornte’s capital is Sebbei, where the deathless Kane absents himself from any sort of liveliness:

Through gates left open — for who would enter? Who would leave? — his horse plodded, past rows of empty buildings and down silent streets. But the streets were kept reasonably clear, and an occasional house showed occupants — sad faces that stared at him with little curiosity. No one challenged him; no one asked him any question. This was Sebbei, where one lived amidst death, where one waited only for death. Sebbei with its few inhabitants living in its silent shell — mice rattling through a giant’s skeleton.

In the midst of so much death the ability to pull off a resurrection is quite a coup de theatre; witness No Name’s dynamite-announced reappearance for the showdown with the Rojos in San Miguel and Kane’s indestructibility in “Cold Light”:

Gaethaa whirled to face Kane. His enemy stepped from out of the fog and smoke and casually strode toward him, sword poised. Rough bandages were bound across his ribs; others made crimson bands across his right shoulder. A murderous light shone from his blue eyes, brutal face drawn in a savage snarl.

Despite the similarly funereal feels of San Miguel and Sebbei, the Kane tale that is structurally closest to A Fistful of Dollars (and Yojimbo, and Red Harvest) is Bloodstone. Once San Miguel has been emptied of those responsible for mostly emptying it of life, No Name has no desire to stick around: “The Mexican government on one side, maybe the Americans on the other side, and me right smack in the middle? Too dangerous.” But Kane is quite prepared to manipulate those more ambitious gangs known as governments in Bloodstone. He makes his first pitch to Dribeck, the ruler of Selonari, in a chapter entitled “A Stranger Brings Gifts.” Eventually, Teres, the daughter of Malchion of Breimen, explains to Dribeck: “We’ve both been bitten by this serpent in our midst. While Kane has played us off against another, he’s been master of his own game!”

The Baxters and the Rojos of San Miguel more than earn what No Name does to them. Selonari and Breimen are pitted against each other by geopolitics well before Kane gets to them, but the Black Prometheus who gave mankind murder is also the human race’s most accomplished warmonger. Still, just as in each installment of the Dollars trilogy No Name’s sleight-of-gunhand manipulations catch up with him and he’s forced to face the music (luckily, it’s by Morricone), Kane the grandmaster ultimately recognizes that he himself is a pawn being moved hither and thither on the chessboard by the crystalloid Bloodstone.

Part Two: Eyes We Dare Not Meet in Dreams

Part Three: Splintered Shards of Time’s Reflection