Howard on the Menu at the Shagadelicatessen

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Decades later it remains a fiendishly effective piece of stage-setting:

For ten thousand years did the Bright Empire of Melnibonè flourish — ruling the world. Ten thousand years before history was recorded — or ten thousand years after history had ceased to be chronicled. For that span of time, reckon it how you will, the Bright Empire had thrived. Be hopeful, if you like, and think of the dreadful past the Earth has known, or brood upon the future. But if you would believe the unholy truth –then Time is an agony of Now, and so it will always be.

Ravaged, at last, by the formless terror called Time, Melnibonè fell and newer nations succeeded her: Ilmiora, Sheegoth, Maidakh, S’aaleem. Then memory began: Ur, India, China, Egypt, Assyria, Persia, Greece, and Rome –all these came after Melnibonè. But none lasted ten thousand years.

And none dealt in the terrible mysteries, the secret sorceries of old Melnibonè. None used such power or knew how. Only Melnibonè ruled the Earth for one hundred centuries — and then she, shaken by the casting of frightful runes, attacked by powers greater than men, powers who decided that Melnibonè’s span of ruling had been overlong — then she crumbled and her sons were scattered. They became wanderers across an Earth which hated and feared them, siring few offspring, slowly dying, slowly forgetting the secrets of their mighty ancestors. Such a one was the cynical, laughing Elric, a man of bitter brooding and gusty humour, proud prince of ruins, lord of a lost and humbled people; last son of Melnibonè’s sundered line of kings.

Elric, the moody-eyed wanderer — a lonely man who fought a world, living by his wits and his runesword Stormbringer. Elric, last lord of Melnibonè, last worshipper of its grotesque and beautiful gods — reckless reaver and cynical slayer — torn by great griefs and with knowledge locked in his skull which would turn lesser men to babbling idiots. Elric, moulder of madnesses, dabbler in wild delights. . .

Very cool indeed. The temporal indeterminacy (borrowed by Robert Jordan?) makes for extra hauntingness, while in the insistence that “Time is an agony of Now” — such a Sixties sentiment — the reader can almost feel the tremors of the coming youthquake. And the “powers greater than men” who step in so banefully, do they echo the Olympians’ animus against Atlantis?

Another echo might be detectable in the specifics when Elric himself is introduced: the Nemedian Chronicles conjure a figure “sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth. . .”; note that Michael Moorcock’s albino is a “reckless reaver and cynical slayer,” and what’s more possessed of “bitter brooding and gusty humour.” (Even if we ignore the similarity to “gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth,” “gusty” is an extremely Howardian adjective).

As it happens MM is more upfront than ever before about REH in his must-read introduction to Del Rey’s Elric: The Stealer of Souls (Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné, Volume I):

Over a period of time following almost exactly the period in which I was writing the first Elric stories, I was inclined to distance myself from the work of Robert E. Howard, even though he had been an important influence (unlike Lovecraft, for whom I had no taste). Over the years I have seen many other writers put space between themselves and their main sources of inspiration and have come to understand it as an important, if not particularly admirable, part of the process of trying to make one’s individual mark.

In recent times I have also given Howard due credit and even by the early 1960s was perfectly happy to announce him as an important influence.

The rather filicidal act by which an artist frees himself from those who came before has been a standard-issue insight since at least Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (1973); it’s great that atop his own eminence Moorcock is now relaxed enough to “undo” the predecessor-slayage. And it’s difficult to resent someone who confides, as he did in his intro to the then-definitive 1998 White Wolf Elric omnibus, “One of my favourite Western titles was Señorita of the Judas Guns,” or appreciatively recalls “Lin Carter’s rediscovery series of fantasy classics, which provided a rich education for those interested in what was still a pretty disparate bunch of books!” As always, the disparity between Author Lin Carter, punchline extraordinaire, and Editor Lin Carter, praiseworthy pantheon niche-holder, is striking.

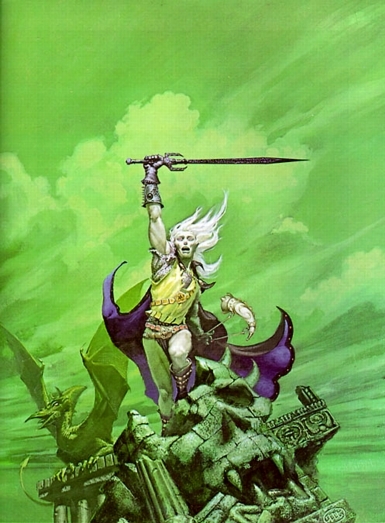

Some visitors to this site may not have revisited Elric since he sported Michael Whelan covers. It’s worth making the trip, not least because to spend time with Elric is to sojourn among the semi-bygone splendors of the Dragon Isle. A scene in Stormbringer wherein Elric’s forbears move “like proud tigers” through a vision got me thinking:

And he seemed to pass beyond the tower’s gleaming walls and see his emperor-ancestors indulging in drug-sharpened conversation, lazily sadistic, sporting with demon-women, torturing, investigating the peculiar metabolism and psychology of the enslaved races, delving into mystic lore, absorbing a knowledge which few men of the later period could experience without falling insane.

Acheron just might be the most maddening case of “Izzat all there is?” in modern fantasy, but the Melnibonè Moorcock reveals to us in passages like that is an efficacious Methadone to quiet the hophead cravings Howard left us with. We only ever learn the name of one Acheronian citizen (unless Baal and Chiron count) and one Acheronian city, but Moorcock offers “Black-ringleted Rondar IV, twelth emperor; sharp-eyed, imperious Elric I, eightieth emperor; horror-burdened Kahan VII [presumably no relation to Jeffrey], three-hundred-and-twenty-ninth emperor,” and of course “Terhali, the Green Empress,” a “powerful sorceress even by Melnibonèan standards,” and likely “the daughter of a union between Emperor Iuntric and a demon.”

Here’s Orastes in The Hour of the Dragon, briefing Xaltotun on events three thousand years gone: “When the day of reckoning came, the sword was not spared. So Acheron ceased to be, and purple-towered Python became a memory of forgotten days. But the younger kingdoms rose on the imperial ruins and waxed great.” From “younger kingdoms” to Moorcock’s Young Kingdoms isn’t much of a stretch, and when Orastes later explains “Behind Xaltotun lie a thousand centuries of black magic and diabolism, an ancient tradition of evil. He is beyond our conception not only because he is a wizard himself, but also because he is the son of a race of wizards,” his words now read like one hell of a hint to any sufficiently ambitious subsequent writer to create an antihero who’s the son of a race of sorcerers, albeit a wayward son. When Elric connives in a raid on Imrryr the Beautiful, it’s as if Xaltotun himself had led the Hybori who sacked Python. I’m not accusing Moorcock of anything except being really, really talented; it’s just a welcome fringe benefit that a statement like the following scratches our Acheronian itch:

Old racial memories were awakened in many when they saw him and they were troubled, fearing him without knowing why, for their ancestors had had great cause to fear the Bright Emperors in the days when Melnibonè ruled the world and a man accoutered as Elric commanded a million eldritch warriors.

Of course the Melnibonèans, like the Zothiqueans, have a penumbral radiance all their own; in one of Moorcock’s most amusing touches, we learn that Meerclar, Lord of the Cats, is fond of “a race which, like him, loved pleasure, cruelty, and sophistication for [their] own sake.” I’ve argued elsewhere that Howard’s Acheron reads like a Thirties premonition of the abysmal depths the Forties would open up, and Melnibonè is equally a product of its own time, when Harold Macmillan’s “wind of change” had attained gale-force intensity. Like the Gormenghast of Mervyn Peake, Elric’s homeland is a reverie of an empire that has collapsed inward upon itself, the better to be mesmerized by its own innermost arcana (Moorcock would soon head the other way — ever-outward — in his Hawkmoon series, wherein the rabid empire of Granbretan, the warlords of which only know they’re alive when they’re annihilating someone, is emphatically expanding rather than contracting).

Their elfin component also differentiates the Melnibonèans from the all-too-human-in-their-inhumanity Acheronians. The Elves I’m thinking of as an influence are mostly those of Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword, an all-time Moorcock favorite, but today Elric’s race also reads like a worst-case extrapolation of Tolkien’s Eldar. Many will disagree with this; in “The Return of the Thin White Duke,” his wonderful introduction to Elric: The Stealer of Souls, Alan Moore memorably describes Elric’s world as “seething, mutable, warped by the touch of fractal horrors,” and accordingly “an anti-matter antidote to Middle Earth [sic], a toxic and fluorescing elf repellent” — thereby missing the extent to which the pointy-eared, fine-featured Melnibonèans come across as a Fair Folk Gone Stylishly Bad, an intensification of what the unchecked imperialist impulses of Fëanor and his followers might have wrought in Middle-earth had there not been a Morgoth to keep them busy (Like everyone else save Clyde Kilby, Christopher Tolkien, and Guy Gavriel Kay, Moorcock had no access to the texts published as The Silmarillion before 1977, so I don’t mean to imply that he was in any way riffing on Tolkien’s First Age Elves when he devised the history of Melnibonè).

One last thing about the Dragon Masters: reading about them is a bit like being beaten with a silk whip; their dreamdust sparkle might be slightly toxic but they’re vividly present on the page in a way that not too much else in the Elric series is.

In a 1963 essay Moorcock admitted “The landscapes of my stories are metaphysical, not physical.” That’s both a strength and a weakness; at times the characters seem to be free-floating, or supported only by ether –and blather (One of the reasons the Corum series improves on Elric by my reckoning is that the clash of symbols doesn’t drown out the rest of the orchestra as often).

Beyond the extent to which Moorcock was “jung and easily freudened” in the intial phase of his career, British sword-and-sorcery at times bears much the same relation to the American original as British rock does to American rock-n’-roll and blues: less spontaneous, more distanced and studied, emulatory and often self-mockingly aware of the emulation, wearing its inauthenticity like a Ziggy Stardust catsuit (Glam, glitter, Brit-pop, even punk; all were costume parties of sorts where the truest faces were masks). And so John Clute freely concedes in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy‘s Moorcock entry that the writer’s stories are “profoundly and multifariously theatrical,” and goes on to note their “smell of greasepaint.” I certainly wouldn’t want to discount the genuine affect in the Elric series; Moorcock has referred to “the wild, undisciplined emotions I poured into my work when the world was younger and if a story couldn’t be produced within twenty-four hours it wasn’t worth writing” — although said emotionalism postures against some extremely stylized backdrops. We need to guard against over-schematization here: where do we put Fritz Leiber, an American, but something of a boulevardier compared to Howard? And what about David Gemmell, a Londoner channeling American directness and lack of artifice?

Alan Moore is way ahead of me in this respect; in his Del Rey intro he playfully contends that Melnibonè was a genuine geopolitical entity until “probably some time in the mid-1940s.” After the Dragon Isle went under, or at least underground, its “shards and relics and survivors,” keepsakes like “mangled scraps of silver filigree from brooch or breastplate, tatters of checked silk accumulating in the gutters of the Tottenham Court Road,” became Swinging London collectibles, counterculture lars and penates until the Bright Empire’s “willful decadence and tortured romance” were relegated to fantasy fiction by “neoconservative theocracies” intent on less aestheticized empire building. This is a delightful conceit, one that I’m tempted to piggyback on by arguing that Their Satanic Majesties Request was the Stones’ most Melnibonèan album, while the influence lingered into the Seventies with Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World and “Oh You Pretty Things.”

Moore himself learned of Melnibonè’s (disputed) existence from “The Fantastic Swordsmen, edited by the ubiquitous L. Sprague de Camp.” Looking back, he deems the contents “a motley armful of fantastic tales swept up under the loose rubric of sword and sorcery, ranging from a pedestrian early outing by potboiler king John Jakes through more accomplished works by the tormented, would-be cowboy Robert Howard to a dreamlike early Lovecraft piece, or one by Lovecraft’s early model, Lord Dunsany, to a genuinely stylish and more noticeably modern offering from Fritz Leiber. ” He continues thusly:

Not content to stand there, shuffling uneasily beneath its threadbare sword and sorcery banner, Moorcock’s prose instead took the whole stagnant genre by its throat and pummeled it into a different shape, transmuted Howard’s blustering overcompensation and the relatively tired and bloodless efforts of Howard’s competitors into a new form. . .

Neither “tormented, would-be cowboy Robert Howard” nor “blustering overcompensation” thrills me overmuch; my suspicion is that Moore, like John Clute before Leo ushered him into a state of enlightenment, is unable to see past the “Texan-ness” of Howard’s surface. So as not to politicize this blog — and I’m thinking of Lyndon Baines Johnson as well as You-Know-Who — suffice it to say that Texas-as-a-signifier has acquired a carousel’s-worth of baggage in the Old World since Quincey Morris in Dracula or Bond’s reflection, in Fleming’s Casino Royale, that “Good Americans were fine people and most of them seemed to come from Texas.”

Anyway, back to Moorcock, who suggests that the Elric stories were “probably the first ‘interventions’ into the fantasy canon, as it were. Later, writers like Stephen Donaldson, Steven Erikson, and Scott Bakker would be similarly criticized.” Good to see that he’s keeping up with recent heavyweights like Erikson and Bakker; were I Moorcock’s co-panelist for a discussion exploring this topic, I would pipe up to argue that “Worms of the Earth” and “The Tower of the Elephant” were in effect interventions before there was much of a heroic fantasy canon to intervene against (for more on ‘Tower” in that capacity, see the essay appended to Grim Lands).

As a damnyankee, I’m not sure how far it is from Lost Pines to Cross Plains, but Howard never seems to be very far from Moorcock’s thoughts these days:

Poor Bob Howard, distraught over the death of his mother, took a shotgun to himself and at least avoided the Conan clones, just as Tolkien never had to see Gandalf bobbleheads or gaming companies lifting and vulgarizing aspects of his work wholesale. I’m sure Howard would have learned how to deal with anything, had he survived, and I still enjoy a fantasy of him as an old guy in a rocking chair, sitting on his front porch and swapping technical tips with his visitors while sometimes privately conceding that the fire’s gone out of the stuff since he first started doing it. Except, of course — and then he’d reel off a list of names crossing a spectrum as wide as the state. Howard could not predict the success of his character any more than I could guess Elric’s future.

That apocryphal shotgun again! I doubt a man with Moorcock’s interests would bother to listen to the Milius commentary track on the Li’l Abner versus the Moonies DVD; no, this must be carelessness, like the reference to “Salem’s H. P. Lovecraft” in his intro to Conan the Phenomenon. Or maybe the shotgun is a manifestation of an unpleasant compulsion to make Howard’s suicide even more violent, even more “Howardian,” in a distorted, cartoonish sense, than it actually was, to “reshoot” the scene with Zapruder film-like splatter. In any event, Howardists are clearly going to have to ride shotgun on the events of June 11, 1936 to keep a shotgun out of accounts thereof.

Howard is back in the introduction to Elric: To Rescue Tanelorn, the second new Del Rey collection:

Sprague and I became good friends and it was he, of course, who first encouraged me to write epic fantasy, when the magazine Fantastic Universe, edited by Hans Stefan Santesson, a much-loved anthologist, wanted to bring such fiction back to the ordinary newsstands. Hans commissioned me to write, with de Camp’s blessing, a new Conan story which, in the end, never materialized, as I have explained elsewhere. While I now have to agree with the purists who have rejected the Conan tales by other hands, we were working in a somewhat different context in which we were a handful of enthusiasts attempting to present Howard’s character to a wider audience.

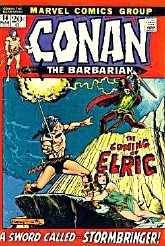

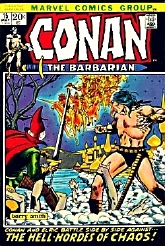

That argument surely sits well with Gary Romeo, but even allowing for the “somewhat different context,” why the implicit certainty that only a twelve-paperback series padded (and adulterated) with pastiches would have broken through to a mass readership, whereas a six-paperback all-Howard-all-the-time series would have flopped ignominiously? And I’m puzzled by the “we were working” phrasing; aside from that abortive Santesson commission, Moorcock’s only Hyborian interloping came when he and James Cawthorn co-plotted issues #14 and #15 of Conan the Barbarian,:

“A Sword Called Stormbringer” and “The Green Empress of Melnibonè” were fun (as drawn by Barry Windsor-Smith, the aforementioned Terhali was as provocative a jade-colored jade as that green dancing girl from Orion in the Star Trek pilot), but bringing Elric and Conan together demonstrated the essential incompatibility of the Moorcock and Howard approaches to sword-and-sorcery. Consider the sense of blacklit wonder at the climax of “Beyond the Black River” when the forest devil engages Conan in conversation, parts the veil to afford a glimpse of the vast and mythological forces that have decreed the Cimmerian’s doom: no way that would work in an Elric story, most of which feature so many hovering supernatural presences as to require a whole tower of air traffic controllers.

Noteworthy among the oddities and rarities of the second Del Rey collection Elric: To Rescue Tanelorn is the recent story “The Roaming Forest,” about which Moorcock has this to say:

I wrote it as a firm nod to Robert E. Howard for an anthology, Cross Plains Universe, done in 2006 for the World Fantasy Convention held in Austin, the nearest large town to where I live in Texas. The book was intended to celebrate and commemorate Howard, and I was flattered to be asked to join in. Readers of Howard, as well as myself, will see a few nods to Conan as well as my own cosmology and its heroes.

Cross Plains Universe was missing from my own bag-o’-swag at the Austin WFC, and slowed by too much barbecue and distracted by good conversations all around, I neglected to demand a copy, so I was glad to catch up with “The Roaming Forest” in the new collection. Turns out Rackhir the Red Archer has been stranded on the Emerald Isle, where he’s known as “Red Ronan”; he swears by “Krim,” a deity of whom it is said that “as was conventional, [he] sent no aid.” Moorcock tries for the hyperactivity of a Howard-style in media res opening in his first paragraph; “The night was a shrieking chaos,” with “wind whipping grass and trees into a madman’s dance.” One of Rackhir’s axe-strokes splits “a head from crown to jaw,” and he addresses a woman he suspects of having played him false as “You hell-bitch!” the sort of language with which Howard enjoyed causing rips in Farnsworth Wright’s bluestockings. And when Moorcock writes “The idea of a forest which could uproot itself and travel where it willed was so nonsensical that Rackhir gave it not a moment of his thoughts,” my guess is he’s having fun with his own reputation as a tireless Tolkien-basher. All in all “The Roaming Forest,” like this year’s Weird Tales story “Black Petals” and 2004’s Elric: The Making of a Sorcerer prequel to Elric of Melnibonè, features Moorcock reconnecting with his pulp-roots and reassuring those of us who were worrying that the locks had been changed on the multiverse.

Moorcock signs off in Elric: The Stealer of Souls with the wish that “If you are new to [the albino], I hope you find him good, rather dangerous company.” No worries there, but simply finding him at all in Elric: To Rescue Tanelorn is another matter. This one will be a whirligig-ride of Moorcockiana for the newcomer, as he or she encounters “The Eternal Champion” (1962) starring John Daker/ Erekosë, then “To Rescue Tanelorn. . .” (1962), starring Rackhir, then Elric pops up in “The Last Enchantment (Jesting With Chaos)” (1962, published 1978), then “The Greater Conqueror” (1963), in which one Simon of Byzantium discovers that Alexander has been reduced to a vessel that filled with, and by, Ahriman (Shades, in advance, of Gemmell’s Dark Prince!) Earl Aubec takes over in “Master of Chaos” (1964), then things get shagadelic with the early Jerry Cornelius outing “Phase 1” (1965) before Elric cuts runeswordedly through the clutter for most of the rest of the book beginning with “The Singing Citadel” (1967).

The albino, often a faithless ally, is an absolute nemesis of bibliographers; here’s a sample excerpt, as tortuous as a Stephen R. Donaldson metaphor, from John Davey’s “Elric: A Reader’s Guide”:

The Bane of the Black Sword (USA 1977/ UK 1984) is a chronological arrangement of selected contents from The Stealer of Souls and The Singing Citadel, compiled in order to bring them in line with the developing series. It was collected in The Elric Saga Part Two (USA only, 1984) with The Vanishing Tower and Stormbringer. For their inclusion in the Elric: The Stealer of Souls omnibus (USA only, 1998 [previously UK only, 1993, as Stormbringer]), the stories have lost both the epilogue, “To Rescue Tanelorn. . .”; and the story “The Flamebringers” has also now been retitled as “The Caravan of Forgotten Dreams.”

Whew. In general, where White Wolf’s Elric: Song of the Black Sword and Elric: The Stealer of Souls back in the Nineties opted for a Lancer-style “character-chronological” sequence, so that The Revenge of the Rose from 1991 is slotted in between The Sleeping Sorceress and The Stealer of Souls, both written much earlier, and Stormbringer is the grand finale, this new Del Rey series seems to have elected (with exceptions) a Wandering Star-style “creator-chronological” (i.e. order of composition) sequence, which places Stormbringer in the first volume. Whatever one’s preference in that respect, the first two collections, to be followed by Elric: The Sleeping Sorceress in November and Duke Elric in March of 2009, are generous to a fault, including as they do “Putting A Tag On It,” the 1961 piece in which Moorcock expressed a preference for “Epic Fantasy” over de Camp’s suggestion of “Prehistoric Adventure Fantasy” as a catchall for the subgenre not yet known as sword-and-sorcery, and primordial artwork like Virgil Finlay’s illustration for “Master of Chaos” in the May 1964 Fantastic Stories of Imagination or a Peter Max-ian cover painting for Mayflower Books’ 1970 The Singing Citadel. Old is however overshadowed by new, by John Picacio‘s covers for the first and third volumes and illustrations for the first; so delectable is his Zarozinia, Elric’s second beloved, that her vermicular fate becomes more tragic than ever before.

Moorcock, who has admitted to having been impressed by the Wandering Star/Del Rey Howards, would seem to be mindful of their precedent when he writes “To give something of the flavour of the time in which the stories were published, we have reprinted the introductory material [E. J.] Carnell attached to them when they appeared for the first time. There are no ‘early drafts,’ I fear, since all the stories were first draft and the only carbon copies were given away to various charity auctions soon after they were published. ” I’m sure Rusty Burke and Patrice Louinet will smile ruefully at the thought of how much easier their task would have been had Howard himself been around to help out on the Wandering Star/ Del Rey volumes, so Betsy Mitchell, the initiator of these fully loaded beauties, is quite fortunate. The intro to Elric: The Stealer of Souls concludes thusly: “It seems Elric will, like the eternal champion he is, keep coming back in various incarnations, but this version is without doubt my favourite and probably the last I shall produce.” It’s my favorite, too, but as I’m doubly pleased as a Howardist as well as an Elric fan by this latest iteration, here’s hoping Moorcock will be here to confound bibliographers by presiding over another edition late in the next decade and another one after that.