Frazetta & Howard, Moorcock & Howard

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Bear with me for this first paragraph. Most people who are fascinated by Alexander the Great know that Mary Renault wrote an Alexandriad, a trilogy of novels about the conqueror’s life and the succession wars that raged after his death: Fire From Heaven (1969), The Persian Boy (1972), and Funeral Games (1981). But some might not be aware that Alexander first appeared in the final chapter of a fourth book, The Mask of Apollo (1966). Renault’s narrator, Nikeratos, a Greek actor who has watched, and narrowly escaped with his life from, Plato’s doomed attempt to bring an ideal city-state into being in Sicily, meets the young prince at the Macedonian court in Pella, and they discuss whether Achilles should have killed Agamemnon and what an alliance between the Achaeans and Trojans for the purpose of eastward expansion might have achieved. Once back in Athens, Nikeratos muses “He will wander through the world like a flame, like a lion, seeking, never finding, never knowing (for he will look always forward, never back) that while he was still a child the thing he seeks slipped from the world, worn out and spent.” What Renault is getting at is that time and chance have denied Alexander exposure to Plato’s poetry, leaving him only the far more prosaic Aristotle. The Mask of Apollo ends this way:

All tragedies deal with fated meetings; how else could there be a play? Fate deals its stroke; sorrow is purged, or turned to rejoicing; there is death, or triumph; there has been a meeting, and a change. No one will ever make a tragedy — and that is as well, for one could not bear it — whose grief is that the principals never met.

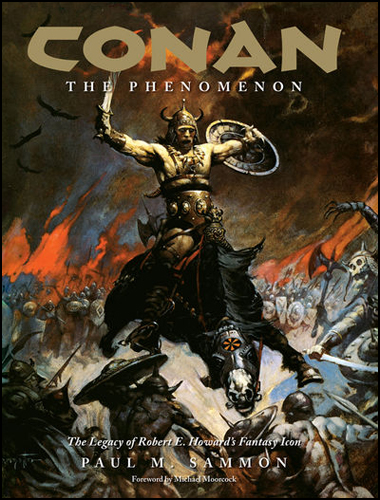

On page 57 of Paul M. Sammon’s Conan: The Phenomenon, Frank Frazetta is quoted (by way of frankfrazetta.com) as saying “I feel a certain sense of loss that Howard isn’t alive to appreciate what I’ve done with Conan.” A certain sense of loss; for me that loss is quite similar to Mary Renault’s even-more-unbearable form of tragedy in which the principals are divided by circumstance or chronology.

As with the Arnie Fenner-produced Icon, Legacy, and Testament before it, Conan the Phenomenon‘s full-page presentation of the great man’s Conan paintings, uncluttered by copy and with plenty of room for edged weapons to be swung, is revelatory. The work is so convincing, so coercive in a way, as to endow Frazetta with a quasi-Howardian authority — if this isn’t what the Hyborian Age actually looked like, it is surely what it felt like at bruisingly cathartic, epiphanic and climactic moments. An artistic license bearing the raised seal of genius means that of all Howard’s interpreters and illustrators, only Frazetta is at liberty to take liberties, second-guess here and free-style there. The Hour of the Dragon is one of the greatest heroic fantasy novels of all time, but when The Beserker, a.k.a. the Conan the Conqueror cover, lunges at me as it does from the front dust jacket of Conan: The Phenomenon, I’m swayed, half-awed and half-cowed, and I start to think “Yeah, an armored skeleton should have fought on the Nemedian side at the Battle of Tanasul.”

The Ultimate Triumph will always be my favorite volume in the Wandering Star/Del Rey Library of Classics, because of the “found” byplay between Howard and Frazetta. Turn the pages of that book and they seem to be egging each other on, jamming in the studio despite being signed to different labels (or assigned by fate to different eras). All honor to the Wandering Star team for creating the simulacrum of a partnership in the absence of any collaborative intent on the part of either collaborator. So nowadays whenever I reach the paragraph near the end of Howard’s March 10, 1936 letter to P. Schuyler Miller where he agrees “Yes, Napoli’s done very well with Conan, though at times he seems to give him a sort of Latin cast of the countenance which isn’t according to type,” I want to blurt, “Just hang on for another three decades, and your notion of doing very well with Conan will be re-defined so far upward as to become orbital debris and endanger space shuttles.” Like Mary Renault said, a tragedy whose grief is that the principals never met.

Anthony Avacato’s impassioned “The Lancer Legacy of Frank Frazetta” in TC V3n5 refers to “a great disappointment in an otherwise stellar collaboration between artist and publisher” when Lancer turned down Frazetta’s request for a raise from $400.00 to $600.00 per painting and farmed 3 covers out to John Duillo, as irradiated a crater of penny-wise, pound-foolish decision-making as the modern era has to offer. Within that shortsighted, tightfisted debacle a lesser but still painful debacle often goes unnoticed. In a better-administered cosmos Frazetta would have painted covers for Conan the Freebooter and Conan the Wanderer, both of which contain Howard classics, rather than daubing lipstick on pigs with Conan the Buccaneer, Conan the Avenger, and Conan of Aquilonia. Not to be unkind to John Duillo, but his middling art met the de Camp and Carter material on its own level (although Marcus Boas would have been even more fitting). Think of the crucifixion in “A Witch Shall Be Born” or the confrontation with Khosatral Khel in “The Devil in Iron”; John Buscema (the cover of Savage Sword of Conan #5) and Boris Vallejo (the post-Duillo cover of Wanderer) strove to rise to the occasion with those episodes, but what might the maestro have done?

Anthony Avacato makes much of Frazetta’s peripheral vision, his half-glimpses of “things suggested as well as obvious” and tendency to “[strain] at the border’s confines,” so the artist’s visualization of Conan on the cross might have featured other predatory onlookers besides the vultures, demons of the desert waiting for the Cimmerian’s soul to leave his overtaxed body. Better yet, one of the stories in Freebooter is “Black Colossus” — imagine a frozen Frazettan frenzy ripped from the climax, as Conan leaps to intercept the “hurtling horror” of Natohk’s conveyance, with its “grisly steed” that is only like a camel and the “black anthropomorphic being” acting as charioteer. Those Duillo covers for Freebooter and Wanderer are scars on a fandom’s heart, like the presence of George Lazenby rather than Sean Connery in the Sixties Bond film that humanized the secret agent more than any other.

Much can be said about Conan: The Phenomenon, and I will try to say a little of it in a future blog-post. Right now I’d like to take a look at the book’s introduction, Michael Moorcock’s “Conan: An American Phenomenon.” Back in TC V4n2 — yes, that issue, the one where, to judge by readers’ reactions, the milk of human kindness was replaced by the sort of sour discharge that could only jet from the non-mammalian teats of an infernal she-beast — in his article “[redacted]” [redacted] wrote about Michael Moorcock’s “Robert E. Howard: A Texas Master.” [redacted] deemed the piece, which introduced Two-Gun Bob: A Centennial Study of Robert E. Howard, “a four-and-a-half-page roller-coaster ride through the tunnel of dimness.”

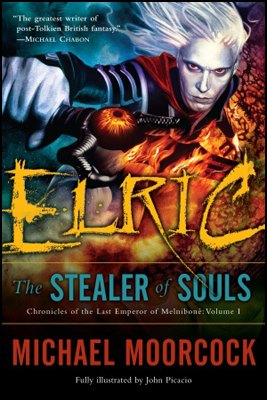

I believe I’m correct in stating that Moorcock was essentially a blank slate for [redacted] before he opened Two-Gun Bob, whereas in my case the slate is as densely doodled-upon as an Etch-a-Sketch where one can only add new strata of scrawls, never erasing what is already there. Those DAW Elric paperbacks with the Michael Whelan covers got passed from Tompkins brother to Tompkins brother only a year or two after the Lancers and the Zebra Howards, although even then Moorcock’s nomenclature, which too often writhed with apostrophes, was a problem. His finest Sword-and-Sorcery, in my opinion, is the Corum Jhaelen Irsei series, the six novels of which have most recently been collected as Corum: The Coming of Chaos and The Prince with a Silver Hand. Moorcock has confirmed that Corum’s world “draws heavily on the Cornish language, Cornwall and Cornish legendry,” all of which have been less strip-mined by exploitative fantasists than other areas of Celtica and therefore imbue the stories with a distinctive filigree of Faerie. For the writer’s very best work, though, it is necessary to look outside the subgenre that usually concerns us here, to Gloriana, or the Unfulfill’d Queen (1978) — which is a little like Cate Blanchett’s two Elizabeth movies had they been a mutable masque set entirely in the greatest Tudor’s skull — to The Brothel in Rosenstrasse (1982), and to Mother London (1988), which deserves to be included in a gift-pack with Peter Ackroyd’s psycho-archaeological London: The Biography and The Clash’s London Calling.

For a not-so-Eternal Champion of Howard’s work, Moorcock, who is also due to appear in Darrell Schweitzer’s The Robert E. Howard Reader, is certainly amenable to reconsidering the Texan in print these days. Why? We can rule out bandwagon-jumping; his own bandwagon continues to trundle along quite nicely, with the Elric saga scheduled for yet another iteration in deluxe Del Rey editions with John Picacio illustrating the first one. No, in all probability Moorcock’s Howardian triptych is the result of his own residence in Lost Pines — no, not Lost Knob — Texas and a recent REH profile that has gotten not only higher but clearer, less obscured by a de Campian haze, than it used to be. That’s how I interpret this sentence: “Mr. Sammon’s book and the recent re-publication of the Conan stories in their original order (Fantasy Masterworks, 2000 and Wandering Star/Del Rey, 2000-2006) helped me recall how good Howard really was.”

My own digressive tendencies have been the despair of several editors, so I feel I can authoritatively label the introduction to Conan: The Phenomenon digression-happy. Sometimes Moorcock digresses to destinations that justify the journeys, as when he dwells on the out-sized Texas weather as a meteorological metaphor for Howard’s emotionalism. En route we get this:

I survived the Blitz and the V-bombing of London, and know how a region can be metamorphosed by violence, how familiar landscapes can become utterly transformed, blooming like terrible flowers before your eyes, but I was still shocked by the sights I came upon in East Texas and Louisiana after Katrina hit.

(Moorcock was born in 1939, but other English war babies have been known to grant themselves participant or veteran status; in several Keith Richards interviews he engagingly claims that Adolf Hitler targeted him personally with multiple Luftwaffe raids — best to stop the Sixties in the cradle, as it were.)

Among the introduction’s other digressions are Victoria’s shepherding of the Hanoverian dynasty to bourgeois respectability, the emigration of irreconcilable Cromwellians to the colonies after the Restoration, Christopher Lee’s tip for surviving America (“Never to forget that you’re British”), the Romantic revival of the Sixties (only to be expected from the creator of Jerry Cornelius), Kit Carson’s exposure to his own fictionalized persona in the camp of some Navajo miscreants, the appeal of cloth blankets to the Iroquois, and the murals on the fifteenth-century parish church where Moorcock lived in Oxfordshire.

Conan fights to keep from being swept away by this flash-flood, and occasionally his black-haired head breaks the surface, in a comment like “When I came across him as a boy I was delighted. He offered pretty much everything I liked to read in one vivid package.” It would be silly to bristle at the “as a boy” there; although not a boys’ writer in the pejorative sense Howard was a young man himself, a native speaker of young man-ese. “That gloriously All-American hero came out of the remote northwest the way his creator came out of the remote southwest,” Moorcock notes — nothing to argue with there. Before getting to what is extremely arguable, at least two non-Conan-related wowsers merit mentioning.

Moorcock cites “the exemplary work of Salem’s H. P. Lovecraft, whose own troubled romanticism influenced Howard and expressed many of his ancestral contradictions.” Salem’s H. P. Lovecraft? The man was of course born in Providence, went on to say “I am Providence” (a line so famous it was carved into his tombstone), and although he both explored and extended the darker corners of New England history and mythology in stories like “Dreams in the Witch House,” assigning him to Salem is no more accurate than writing “Glastonbury’s Michael Moorcock” or “San Antonio’s Robert E. Howard” would be. This one should have been caught.

Similarly worrisome is the following:

Howard saw the old virtues fading as the Depression and the Dustbowl allowed predatory banks and loan companies to prey on the pioneers, until folk heroes like John Wesley Harding [sic] and Bonnie & Clyde arose to symbolize the desperate individuals who took the law in their own hands and stood up against the wealthy industrialists and resource-owners ensuring their own well-being at the expense of the rest of us.

The implication here is that the triple-monickered triggerman and Bonnie & Clyde were contemporaries, both imbibers of the Depression’s grapes of wrath. Sixties scenester that he was, Moorcock likely bought or had played for him a copy of Bob Dylan’s 1968 John Wesley Harding, but Harding/Hardin can only be understood against his specific historical backdrop of carpetbagging, the Emancipation Proclamation, and Texans who spat out the bitter brew of defeat. See Gary Romeo’s “Once I Was John Wesley Hardin!” in TC V3n3 for details.

I’m dubious about Moorcock’s assertion that de Camp, whom he labels “Howard’s greatest publicist and supporter” back when he, MM, was a teenager, “never made a great deal of money from his enthusiasm” — a definition of “a great deal of money” is required here. Perhaps Gary Romeo or Scotty Henderson has researched this matter; de Camp incontrovertibly fought like grim death, or the bird-napper of a golden egg-laying goose, to prevent any de-coupling of his pastiches from the Conan canon.

[LEO ADDS: the de Camp letters at the Harry Ransom Center clearly show that the de Camps became millionaires off of their Howard earnings (fighting ceaseless court battles for a decade and shelling out lawyer fees in the deep five figure-range to do so). A typical post-CPI effusion (written between Caribbean cruises) is this one to E. Hoffmann Price, Nov. 27, 1977: “We threw a big bash at the Merion Golf Club — black ties and all…it went off so well that, if the Conan money keeps coming, we might make it an annual affair. Yes, I had really rather write noble tomes on the causes and curses of civilization; but Conan is where the money is….” Now back to Steve….]

But where Moorcock really falls down is in his discussion of King Conan: “Somewhat in denial, Conan couldn’t resist the top job and property bonanza (Feudalistic cultures, after all, give ownership of the country to the king) when it was offered.”

Why should he have resisted, when Howard seeded stories like “Black Colossus,” “Beyond the Black River,” and “Red Nails” with indicators that Conan was just waiting for a sizable throne to happen along? And “when it was offered” is all wrong. Phrases like “When I overthrew the old dynasty,” “When King Numedides lay dead at my feet and I tore the crown from his gory head and set it on my own,” “I had prepared myself to take the crown,” “When I overthrew Numedides,” “I climbed out of the abyss of naked barbarism to the throne and in that climb I spilt my blood as freely as I spilt that of others, ” “I strangled him on his throne the night I took the royal city” are always active and never passive, taking, usurping, wresting away from rather than being offered. Yes, like Kull before him, Conan found allies and adherents when he struck for the crown (the story of how he won over Trocero and Prospero, whose Poitain was far from the Pictish frontier, would perhaps have been told in Wagner’s Day of the Lion), but does anyone doubt that he was the architect and instigator of his own elevation?

Moorcock does no better when he writes “[Conan] felt awkward with the responsibilities and problems of power and could never identify himself with his nation, the way the better-respected European monarchs did.” Not so! In the very first Conan story, a revered sage and defender of his adopted nation assures him “Your destiny is one with Aquilonia.” Why should we question the Cimmerian’s sincerity when he recalls to his captors Strabonus and Amalrus that “The land was torn with the wars of the barons, and the people cried out under oppression and taxation”? And Howard is even more explicit a bit later in the same story:

He would not sell his subjects to the butcher. And yet it had been with no thought of any one’s gain but his own that he had seized the kingdom originally. Thus subtly does the instinct of sovereign responsibility enter even a red-handed plunderer sometimes.

By the time of The Hour of the Dragon, the true affair of the heart is between Conan and Aquilonia, not Conan and Zenobia. Patrice Louinet covers this ably in “Hyborian Genesis, Part Two,” but Moorcock shouldn’t even need to read Louinet — reading Howard should be enough. No, I don’t expect him to keep up with the secondary literature; after all, he has his own multiverse to manage. But the time for botching the basics — incredibly, one newspaper reviewer of The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian claimed that nothing in “Queen of the Black Coast” indicated that the barbarian felt very much for Bàªlit — is at one with Nineveh and Tyre, which is to say over. Future Names of Power brought in to bigfoot Howard projects need to be held to the standard set by KEW and Fritz Leiber way back when.

LEO ADDS: as an addendum to Steve’s closing comments above, the de Camp letters also mention Wagner. Typical comment, from a missive to Vernon Shea dated September 25, 1977: “Nowadays, Conan and his creator keep me busy. Robert Howard, I have learned, was a lot stranger than most of his more uncritical admirers, like Karl Wagner, would care to admit. There’s a parallel to the Mosig-Lovecraft relationship there.”

Dirk Mosig was the most erudite and successful challenger to de Camp’s HPL biography in the 1970s (for all his prolificacy, Joshi is but a pale shadow of Mosig as an HPL critic), arguing with the science fiction grandmaster at length in Fantasy Crossroads, a battle royale that had the same sort of eye-opening effect in Lovecraft fandom that Herron’s “Conan vs. Conantics” had with Howardians. De Camp saw the likes of Mosig/Wagner/Herron/Glenn Lord as “fanatics” leveling fanboy “jeremiads” at him, uncritical cult-like worshipers of hack authors manifestly undeserving of such devotion. In a letter to Chet Clingan dated August 25, 1977 de Camp explained:

These fans belong to a group that regard Howard’s writings as a kind of holy writ, not to be tampered with or added to by lesser mortals. They are entitled to their opinion; but, having read a good deal in the course of my life, from Homer to Saul Bellow, I can’t take Howard’s writings quite so seriously as all that. Good entertainment, sure, but Tolstoy and Hemingway have nothing to worry about.

Of course de Camp took the money seriously, warring for decades over the right to collect on Howard’s stories. But the stories themselves were just product. He never understood that it was this clueless critical attitude that rankled fans far more than his involvement with or profiting from Howard publishing. After all, Wagner wrote his share of (in my opinion lackluster, in Steve’s opinion laudable) Howard pastiches, without establishing himself as a pariah among fans. But at base Wagner could clearly see the genius at the core of Howard’s writing, the artistry that kept people coming back for more decade after decade.

It wasn’t so much that Wagner and others were “uncritical” admirers of Howard the Man, but that de Camp was incapable of being intelligently critical about Howard the Writer. As he told Clingan on July 6, 1977: “According to the sales figures on the Conan paperbacks, the reading public shows no preference for the purely Howard volumes over those by my collaborators and myself; they rate just about equally.” Now to a good critic that’s as inane as saying that Frazetta wasn’t important to the series because the non-Frazetta illustrated volumes sold just as well as the rest. Or, to broaden the argument beyond REH, you may as well claim that there’s no real difference between the Rolling Stones version of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” and the one Britney Spears did decades later, because, hey, they both moved a lot of CDs. Such appraisals lack any sense of critical thought, an understanding of what’s great and why compared to what’s just filling pages for a fleeting modern audience.

De Camp readily admitted that his Conan stories weren’t as good as Howard’s (attributing that not to a dearth of talent or “seriousness” but to Howard’s being “crazy”), but he only needed to check the sales figures and the accolades received over a long career to confidently assume that he nevertheless was worthy of writing additional Conan tales and surgically weaving them into Howard’s classic canon. He wasn’t, anymore than Herman’s Hermits “I’m Henry VIII, I Am” could ever be considered on a par with “Satisfaction” by virtue of having displaced the latter atop the charts back in 1965.

Sure, de Camp’s Conan stories sold well back in the hysteria of the Howard Boom, when everything with Howard and/or Conan on the cover sold wonderfully. But even at the time readers with decent critical minds were rebelling, pointing out the enormous difference in quality and execution. What happened in the wake of all this? The de Camp contributions to the Lancer series are out of print and likely to remain so, whereas Howard’s stories are enjoying yet another renaissance. Now a true critic like Wagner could clearly see and explain why this happened, even way back in the ’70s — in fact, he was pushing hard for this division between creator and pasticheur at the time. A guy who has no critical grasp, on the other hand, is baffled, and might resort to blaming angry fanboy “fanatics” for rating their “idol” way too highly, while stumbling on thinking that it’s all more or less the same, just product, not to be taken seriously except insofar as you can get paid.

You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, and the de Camp letters at the University of Texas, Austin show a man dying of thirst at the cusp of a great freshwater lake of “untold shimmering fathoms,” getting paid millions to lip-sync “I can’t GET no! Sat-is-FAC-tion!” and wondering why the Howard groupies weren’t all lining up around the block.