Guest blogger Morgan Holmes weighs in on a Sword-and-Sorcery post which appeared on this site a few weeks ago:

MORGAN: Steve Tompkins mentioned a couple weeks back about “various knights of doleful countenance” pining for mass market Elak of Atlantis. I like David Gemmell, have been reading him for over ten years, and view him as a standard bearer for the genre at a time when no one else did. These are two different issues though. A problem with Sword-and-Sorcery is the original fiction was never entirely presented in paperback form. Sword-and-Sorcery has been presented fitfully in bits and pieces since the late 1960s.

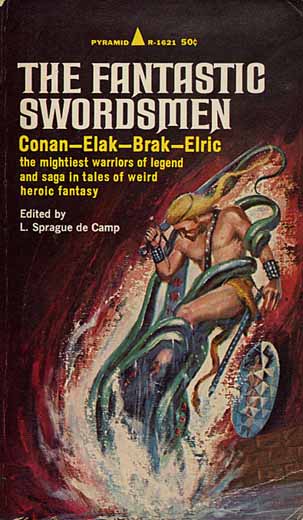

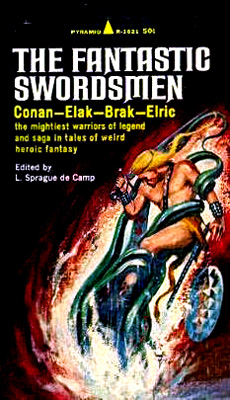

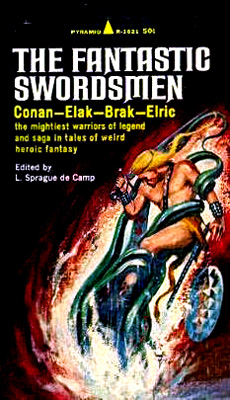

L. Sprague de Camp was the first to present Sword-and-Sorcery in paperback form with anthologies from Pyramid such as Swords and Sorcery (1963), The Spell of Seven (1965), The Fantastic Swordsmen (1967), and Warlocks and Warriors (1970). The de Camp anthologies were pretty good introductions to the genre for neophytes. Pre-pulp stories by Lord Dunsany were generally included; Robert E. Howard, C. L. Moore, and Clark Ashton Smith from the pulp years. He would include a story or two from 1950s digest magazines by writers he knew (Poul Anderson, Fritz Leiber). De Camp even managed to include fairly new fiction by Michael Moorcock, John Jakes, and Roger Zelazny in those anthologies. Robert E. Howard is present in 100% of the anthologies, Lord Dunsany 100%, Clark Ashton Smith 75%, Fritz Leiber 75%, Henry Kuttner 75%, C. L. Moore 50%, H. P. Lovecraft 50%, and L. Sprague de Camp 50% (one story co-written with Robert E. Howard).

The Lin Carter-edited anthologies are more surveys of fantasy fiction as opposed to being strict anthologies of Sword-and-Sorcery. Anthologies such as The Young Magicians (1969) and New Worlds for Old (1971) have E. R. Eddison, William Morris, and James Branch Cabell juxtaposed with the pulp era of Robert E. Howard, C. L. Moore, and H. P. Lovecraft to post WWII fantasy of J.R.R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. Carter’s most Sword-and-Sorcery-oriented anthology is The Magic of Atlantis (1970) which is completely made up of pulp reprints except the Lin Carter story. Carter managed to include obscure Nictzin Dyalhis and Edmond Hamilton stories in the book.

The two anthologies edited by Hans Stefan Santesson, The Mighty Barbarians (1969) and The Mighty Swordsmen (1970) were derivative and inferior with a majority of the stories already found in other anthologies. There were new Lin Carter Thongor stories in each book. Maybe Santesson thought Lin Carter would entice people to buy the book.

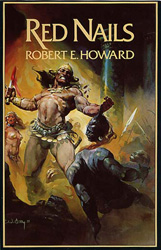

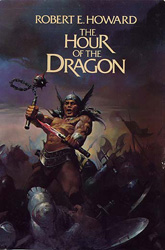

That was about it for reprint Sword-and-Sorcery anthologies. Flashing Swords and the Swords Against Darkness series were made up of new fiction later in the 1970s. We had the adulterated Conan “edited” by L. Sprague de Camp, incomplete Clark Ashton Smith from the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, Jirel of Joiry by C. L. Moore (supposedly edited by Lin Carter), the two Prester John novels by Norvell Page, and the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser books by Fritz Leiber. That’s it! Everything else marketed as Sword-and-Sorcery in the late ’60s was new or science fiction disguised as Sword-and-Sorcery. As it was, the Jirel collection by Paperback Library missed a story ( “Quest of the Starstone” ) and the Sword-and-Sorcery of Henry Kuttner was never collected. Kuttner wrote four stories about Elak of Atlantis for Weird Tales and two stories about Prince Raynor for Strange Stories. Those six stories collected into one book would have given enough page count for a typical late 1960s paperback. No one bothered to pitch the idea or do the work of collecting six stories together. There was little interest in delving into the pulps to find out what else might be found. Savage Heroes and The Barbarian Swordsmen were pretty much retread anthologies of what had already been done.

It was not until 1987 when the first Echoes of Valor book came out edited by Karl Edward Wagner. This was the first and last attempt to methodically anthologize pulp Sword-and-Sorcery including a fair amount of obscure material. Wagner managed to get the more elusive C. L. Moore stories into print and also present Manly Wade Wellman’s Hok the Cro-Magnon stories for the first time in paperback. The first Echoes of Valor included a Kuttner story ( “Wet Magic” reprinted from Unknown ). The second volume had “Quest of the Starstone” co-written with C. L. Moore, a notoriously hard story to find. The third and last volume of Echoes of Valor included both Prince Raynor stories reprinted from Strange Stories. EoV III is also the closest we have ever come to having a Nictzin Dyalhis collection. Wagner had hoped to edit a fourth and fifth volume of Echoes of Valor but that was not to be. The series did not sell very well for Tor. It didn’t help matters that each book came out in two years intervals. If Wagner had five books ready to go at the outset, we might have a landmark series chronicling the early years of Sword-and-Sorcery fiction. Wagner might have presented lost gems from Planet Stories and Fantastic Adventures to a modern audience. He was beginning to excavate the genre the way Sam Moskowitz had with early science fiction. Science fiction had its massive landmark anthologies edited by J. Francis McComas or Groff Conklin in the 1940s and early 1950s rescuing the best of science fiction of the 1930s and ’40s. We never had that with Sword-and-Sorcery.

You can track down the heroic fantasy of Henry Kuttner but it takes some work. The stories are scattered among various horror and heroic fantasy anthologies. I will here mention that Gryphon Books did collect the Elak stories back in 1985. The book had 500 copies and was marred by being printed with a dot matrix printer. The end result is unreadable. The time has come and gone for mass-market collections for the Sword-and-Sorcery fiction of Henry Kuttner. If it happens today, it will be some small press who produces the book and not Del Rey, Ace, Tor, or Baen though one can always hope.

STEVE ADDS: This would have been a much more enjoyable discussion to have before events prematurely relegated Druss and the other Gemmell heroes to the same past tense where Elak dwells. On his way from the Hans Stefan Santesson anthologies to Flashing Swords! and Swords Against Darkness Morgan skips over a treasure trove that deserves its own Germanic dragon: DAW’s The Year‘s Best Fantasy Stories #1-6, edited by Lin Carter. I’m biased becuse #3, in 1977, introduced me to both KEW’s Kane (before that I knew Wagner only as the author of Legion From the Shadows) and Charles R. Saunders’ Imaro, but with George R.R. Martin’s “The Lonely Songs of Laren Dorr,” Gardner Fox’s “Shadow of a Demon,” C.J. Cherryh’s “The Dark King,” and Ray Capella’s “The Goblin Blade” backing up Saunders and Wagner, that might be the pick of the litter. Most of Carter’s selections were either sword-and-sorcery or dark fantasies that were hardly a chore for the S & S aficionado to read; true, there’s Carter himself to deal with — his posthumous collaborations with Clark Ashton Smith are slightly less welcome than would be an actual ghoul chowing down on the CAS bones to get at their marrow — but I for one find Andrew Offutt in the 5 Swords against Darkness collections to be a more erratic editorial presence. Carter manages to rise above himself in #4‘s Niord/Hialmar pastiche “The Pillars of Hell,” and the Thongor stories he chose for the series offered a much less cloddishly Burroughsian barbarian than the Thongor novels of the Sixties. Plus, his excoriation of Terry Brooks at a time when epic fantasy hopheads were ramming their cars through bookstore windows to score copies of The Sword of Shannara makes up for quite a few of the sins of omission and commission in Imaginary Worlds. #4 also features Poul Anderson, Tanith Lee, and Ramsey Campbell wearing their heroic fantasy helms — seriously, any sword-and-sorcery library should include these collections. Carter was still capable of being a force for good in the mid-Seventies when he wasn’t hitting himself in the face with custard pies (think Ganelon Silvermane in the Gondwane novels or Amalric the Man-god in Flashing Swords!)

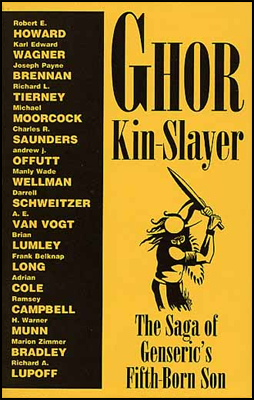

Sometime in the late 1970s, the Rev. Jonathan Bacon (a one-time member of REHupa) came up with a fairly cool idea. Bacon was the editor of Fantasy Crossroads, a Howard-centric fanzine. Through Glenn Lord, Bacon had acquired the Robert E. Howard fragment, “Genseric’s Fifth-Born Son” (the title derives from Lord, as far as I can ascertain), a part of the “James Allison” series of reincarnation tales. Bacon thought it would be interesting to bring together many of the active fantasy authors at that time and have them “complete” Howard’s fragment in a round-robin fashion. Robert E. Howard himself had participated in something similar when he wrote a chapter for “The Challenge From Beyond,” a round-robin tale published by the fanzine Fantasy Magazine in late 1935. In some ways, Bacon was just following a trail that REH had helped blaze. However, he chose to discard the Lord title for the fragment as a title for the entire work, deciding upon Ghor, Kin-Slayer as being a better designation.

Sometime in the late 1970s, the Rev. Jonathan Bacon (a one-time member of REHupa) came up with a fairly cool idea. Bacon was the editor of Fantasy Crossroads, a Howard-centric fanzine. Through Glenn Lord, Bacon had acquired the Robert E. Howard fragment, “Genseric’s Fifth-Born Son” (the title derives from Lord, as far as I can ascertain), a part of the “James Allison” series of reincarnation tales. Bacon thought it would be interesting to bring together many of the active fantasy authors at that time and have them “complete” Howard’s fragment in a round-robin fashion. Robert E. Howard himself had participated in something similar when he wrote a chapter for “The Challenge From Beyond,” a round-robin tale published by the fanzine Fantasy Magazine in late 1935. In some ways, Bacon was just following a trail that REH had helped blaze. However, he chose to discard the Lord title for the fragment as a title for the entire work, deciding upon Ghor, Kin-Slayer as being a better designation.