Cold Light and Winter Soul-Reflections

Wednesday, August 8, 2007

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

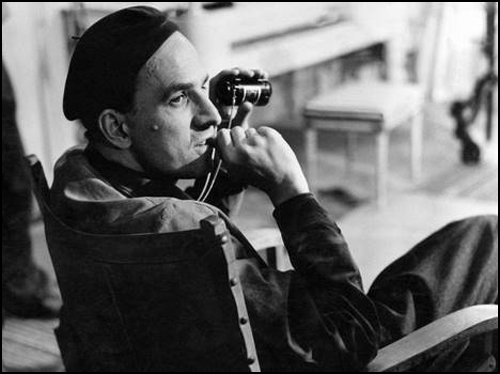

Has anyone ever devised a deadlier zinger about a major author than Oscar Wilde’s “Henry James writes fiction as if it were a painful duty”? Many people, among them some professed cineastes, would also claim that Ingmar Bergman made movies as if it were a painful duty, or at least made movies the watching of which is necessarily a painful duty. After the Swedish director’s death last week just about every obit or tribute online that offered a comments section was gate-crashed by reverse snobbery-afflicted knuckle-walkers and know-nothings who sneered that the Bergman cult was/is an affectation of pseudo-intellectual, popular culture-despising coastal or campus elites — blue-staters, most likely supporters of public television and Volvo drivers. Oh well, in many ways Bergman was the heir of Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, so we might say attacks by trolls are part of his Scandinavian heritage.

Jeezis wept, Joe Blog-Reader thinks, is he really going to inflict a post about Ingmar Bergman on us? I can’t help it, having arrived in New York City as a college freshman just in time for the twilight of the pre-videocassette arthouse/repertory cinema era. It didn’t take long before I had ascertained that Fellini and Fassbinder were not for me, but Buñuel, Kurosawa, and especially Bergman were.

The most entertaining book about “that Swede,” as Peckinpah once referred to him, is Vernon Young’s 1971 Cinema Borealis: Ingmar Bergman and the Swedish Ethos. “Cinema Borealis” captures much of the director’s appeal; having been introduced to the phrase “The Northern thing” by Lin Carter, my callow collegiate self sensed that here was a dour, post-Lutheran twentieth century continuation (with nihilism subbing for Ragnarà¶k). And more importantly, here were snow-blindingly beautiful Nordic women, the unforgettable Bergman actresses, whom I lost no time in casting in Howardian roles. The Bibi Andersson of The Seventh Seal (1957) and Wild Strawberries (also 1957) as Atali. The Ingrid Thulin of Wild Strawberries or The Magician (1958) as Brunhild in “The Gods of Bal-Sagoth” or “the fire and wonder that was Gudrun” in “The Garden of Fear.” The Gunnel Lindblom of The Virgin Spring (1960) or The Silence (1963) as Kormlada in “The Grey God Passes.” The Liv Ullmann of Persona (1966) as Aluna in “Marchers of Valhalla,” or Freda in Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. It’s a pity the term “Stockholm Syndrome” means something else entirely. . .

Yes, the mere mention of entities like Janus Films and The Criterion Collection denotes tedium for some, but Bergman had a gift for the Gothic (After all, the Goths supposedly came from what would become Sweden). Here and there during his career, he threatened to become a weird fictionist who worked with the camera rather than the typewriter or word processor — see the dream or fantasy sequences in Wild Strawberries, The Magician, and Through a Glass Darkly (1961), or The Hour of the Wolf (1968) in its fell entirety. The Sixties, miraculously bountiful in terms of reinvigorated Westerns and secret agentry, did not produce many great horror movies, aside from Romero’s Night of the Living Dead and The Hour of the Wolf (By way of contrast, the Seventies, which were left with the chore of sifting through the wreckage of the Sixties, were an absolutely killer decade for horror) Discussing the genesis of The Hour of the Wolf, Bergman remembered “I never have any sun in the room where I write. I was sleeping in this room too, and after a few weeks I had to stop. The demons would come to me and wake me up and they would stand there and talk to me. It was very, very strange.” If the demons come often enough, and purposefully enough, does it really matter whether they come from within or without?

Most of The Silence (1963) takes place in the Hotel Europa, in the capital of some terra incognita wracked by invasion or putsch. Bergman was going for “a rendering of a hell on earth,” and his hotel is even scarier than the Overlook; had it been equipped with detectors for dread like those now required to guard against carbon monoxide, they would have been sounding the alarm in every room. In his essay “Why Horror Fiction?” (included in the 1999 collection Windows of the Imagination) Darrell Schweitzer lists Fanny and Alexander (1982) as one of the very, very few “proper horror films” of recent decades.

Bergman was not interested in the Dark Ages (preferred longeurs to longships, I can hear someone muttering) or perhaps he suspected the real Dark Ages of having begun around 1939. But if we turn to The Seventh Seal and The Virgin Spring, we’re talking two of the absolutely must-see medieval films (my short list would also include Excalibur, Flesh and Blood, and the Pythonian diptych of Holy Grail and Jabberwocky). An old friend of ours from “The Grey God Passes,” the tussle between Odin and the White Christ for believers, underlies The Virgin Spring, about which Bergman later said “I wanted to make a blackly brutal, medieval ballad in the simple form of a folk-song.” Wes Craven Americanized the material and emptied a bottle of ketchup all over it in The Last House on the Left (1972). No other character returning home from the Crusades, not even Sean Connery in Robin and Marian, is as memorable as Antonius Block in Seal, played by Bergman’s frequent lead actor Max von Sydow, who can claim the dubious distinction of having been given nothing to do in both a James Bond and a Conan movie (he was wasted as Blofeld in Never Say Never Again and King Osric in Conan the Barbarian).

The Seventh Seal and The Virgin Spring also figure in the Ingmar Bergman-Karl Edward Wagner connection the title of this post is intended to hint at. For my money the most powerful heroic fantasy collection by an author who was alive at the time of publication is Wagner’s Night Winds (1978) — and I risk that assertion as someone who is hopelessly devoted to Fritz Leiber’s style and storytelling. “Sing A Last Song of Valdese,” the last story in Night Winds, is also the shortest, but still as brutally effective as the final nightmare before one wakes up drenched in sweat (The first time I read “Valdese” it took me days to get over this sentence: “But they spared him his eyes so that he might watch what they did to her, and they spared him his ears so that he might listen to her screams”. I’ve also wondered for years about the influence of The Virgin Spring and especially The Seventh Seal on the story.

Aficionados need no recap of “Valdese.” Suffice it to say that during a stopover at an inn in a lamia-haunted mountain region, Wagner’s hero-villain, who has been masquerading as a priest, intervenes just as a long-planned attempt to avenge an atrocity fifty years in the past looks like it might fail. Kane, by virtue of being Kane, enables that old crime’s surviving victim to summon “a tall figure in a tattered cloak of grey.” The scene goes black and upon regaining consciousness Kane can’t exit the now thoroughly uninhabitable ruins of the inn fast enough:

Outside he breathed raggedly and glanced again at the sky.

The mist crawled in wild patterns across the stars. And Kane saw a wraithlike figure of grey, his cloak flapping in the night winds. Behind him seemed to follow seven more wraiths, dragging their feet as if they would not follow.

Then another phantom. A girl in a long dress, racing after. She caught the seventh follower by the hand. Strained, then drew him away. The Grey Lord and those who must follow vanished into the night skies. The girl and her lover fell back in an embrace — then melted as one into the mist.

In “Valdese” the danse macabre or Totentanz of The Seventh Seal as Death leads his latest recruits over the hill becomes airborne. Note that in both film and story the young lovers escape; I doubt the imagery of Wagner’s fadeout would exist without Bergman’s. The title of one of the non-Kane KEW stories is “The Fourth Seal,” and he was a member of the generation for whom the Bergman films of the late Fifties and Sixties were initiation rites of sorts. There must have been an arthouse or two near the campuses of Kenyon College in Ohio and the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where he put in his undergrad and med school time respectively. The character of Passlo in Valdese even says “I foresee a pleasant evening of theological discussion,” as if to poke fun at Antonius Block’s spiritual crisis. Would that Wagner had come close to Bergman’s longevity and productivity…