After Aquilonia and Having Left Lankhmar: Sword-and-Sorcery Since the 1980s

Friday, July 25, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

[When Howard Andrew Jones writes about sword-and-sorcery and the desirability of “putting a new edge on an old blade,” it behooves those of us as protective of the subgenre as he is to pay attention, and perhaps pay him the compliment of trying to put our own thoughts in order. To that end, and with a bemused glance at a June 22 post by Gary Romeo, who never loses an opportunity to generalize about Howard purists even if he did lose the chance to celebrate the centennial of his nearest and dearest, I’m rolling out the following article, originally written in 2006 for an anthology that apparently could not be more snake-bitten were it to traipse barefoot through Stygia]

The subgenre of modern fantasy with which Robert E. Howard is nearly synonymous died down in the mid-1980s but did not die out. Far from it; sword-and-sorcery proved to be as difficult to kill as many of its protagonists. But before we can celebrate Howard’s legacy by following the subgenre’s fortunes for the last several decades, we need to establish what we mean by sword-and-sorcery. For starters, what is meant at least for the purposes of this article is an approach to heroic fantasy that became aware of itself when Howard decisively expanded on the promise and premise of Lord Dunsany’s 1908 story “The Fortress Unvanquishable Save for Sacnoth” with “The Shadow Kingdom” in 1929.

The verb “expanded” is chosen with no disrespect whatsoever intended toward Dunsany’s story; it is possible that during his much-debated involvement with sword-and-sorcery, L. Sprague de Camp never did the subgenre more of a favor than when he selected “The Fortress” for his anthology The Fantastic Swordsmen (1967).

(Here, on the other hand, Leo argues that the only place for poor old “Sacnoth” in an S & S muscle car is: the ejector seat)

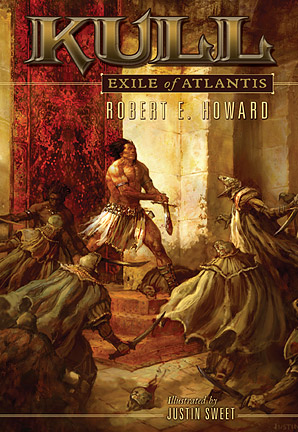

Dunsany’s young swordsman Leothric and the sorcerer Gaznak, “the greatest magician among the spaces of the stars,” meet in a climactic duel as so many swordsmen and sorcerers have done ever since, but the special FX and local color (vampires slumbering in the stronghold’s rafters, a pet dragon hand-fed “tender pieces of man” have rarely been as dazzling. Still, hero and setting leave room for growth if not necessarily improvement, and in “The Shadow Kingdom” Kull, who questions reality as he would a captured conspirator, is too singular a character to be contained by a single story. Leothric is barely even a character, being merely a means to an end, the end of Gaznak. Kull possesses a past — he’s haunted by his younger, wilder self, another spectral presence in a story full of them — and a future, at least a little of which Weird Tales readers got to see in “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune” and “Kings of the Night.”

“The Fortress Unvanquishable” offers a village, Allathurion, in “a wood older than record,” and a “Land Where No Man Goeth,” the site of Gaznak’s lair when he isn’t riding comets. Other than that, a suspicion that Dunsany’s backdrop exists only as far as the story’s first and last paragraphs is not unwarranted.

By way of contrast the world of the Seven Empires (which Howard would only later name the Pre-Cataclysmic Age) extends across the “green roaring tides of the Atlantean sea” to “the far isles of the sunset,” and is lavishly backstoried, what with its “sudden glimpses into the abysses of memory” and account of the aeons-abiding struggle to make human history human, or the “ghosts of wild wars and world-ancient feuds” that whisper to Kull and Brule the Pict.

Sword-and-sorcery’s geography is “designed for more to happen,” as the subgenre’s entry in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997) emphasizes, which means that the characteristic protagonist, from Kull onward, is he or she to whom that “more” happens. The resulting stories are epic in eventfulness rather than in length; after all, the next adventure is impatiently awaiting its cue.

So the difference between Dunsany’s Leothric and Howard’s Kull of Atlantis is not only the arrival of a frontier-fashioned, if educated, American voice with a Texas accent, but a changeover from self-contained to sequel-sustained storytelling.

Fritz Leiber, arguably second only to Howard as a tutelary deity for sword-and-sorcery, foresaw that any quest for definitional exactitude would involve scrambling after a will-o’-the-wisp.

Even as he proposed the cloak-and-dagger, blood-and-thunder analog as a playful or placeholder name for stories like the Conan series or his own Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in the second, April 1961 issue of the fanzine Ancalagon, he noted “Of course there will always be wide fringes of borderland around a story-area like this,” and warned that too much pedantry, too much misuse of broadswords and battle-axes to split hairs rather than more dignified and deserving targets, might “result in a kind of nonsense.” (Case in point, the aforementioned Encyclopedia of Fantasy “sword-and-sorcery” entry, which unhelpfully suggests that both S & S and heroic fantasy “are aspects of adventurer fantasy”

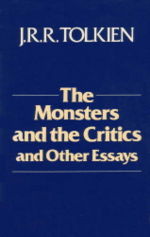

Thus cautioned, we are now ready to call some expert witnesses, the first of whom, J.R.R. Tolkien, revolutionized Beowulf studies on behalf of Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and the dragon in his 1936 lecture “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” while also saying essential things about heroic fantasy as powerfully and poetically as they can be said.

Tolkien speaks of “a man faced with a foe more evil than any human enemy of house or realm,” and of “battle with the hostile world and the offspring of the dark.” When he stresses that “the monsters do not depart, whether the gods come or go,” we have our justification for the sword-and-sorcery imperative that humankind be able to clear a little space for itself, torch-lit and steel-shielded, in an environment that is ceaselessly and outrageously hostile.

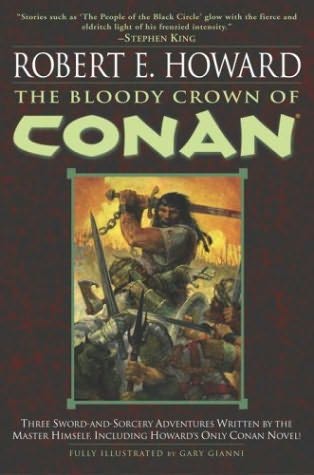

Tolkien, of course, is almost always seen as the grandsire of another sort of fantasy, “epic” or “high,” although some of the peak moments in the Christopher Tolkien-compiled History of Middle-earth demonstrate that his father was quite capable of being a great heroic fantasist whenever he wanted. Still, this might be as good a place as any to state of the thematic overlap between Howard-descended and Tolkien-descended fantasy that sharks might move through the same waters as whales, but they do so at a different speed and in pursuit of different sustenance while covering different distances (That having been said, some readers will be blindsided by how much more sharkish than cetacean 2007’s The Children of Húrin is). Sword-and-sorcery is rarely about restoration but frequently about upheaval and overthrow. Much muscular effort is expended on keeping the past in the past, and Old Orders are no more welcome than any other revenants. Dark Lords, those half-dictator/half-diabolus progeny of John Milton’s Satan like Tolkien’s Morgoth and Sauron, Stephen R. Donaldson’s Lord Foul in The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, or Guy Gavriel Kay’s Rakoth Maugrim in The Fionavar Tapestry, are usually habitués of epic fantasy. They would unbalance sword-and-sorcery stories, where just surviving against archmages like Xaltotun in Howard’s lone Conan novel The Hour of the Dragon is hard enough without having to take on fallen angels or demonic Outsiders hellbent on enslaving or exterminating all forms of life.

Our second expert witness is Howard himself, by way of a boast to his friend Tevis Cyde Smith in December of 1932: “My heroes grow more bastardly as the years pass.” This tells us something of the subgenre’s scapegrace and seldom shining-armored nature, its pragmatic willingness to side with the lesser and more human of two evils, especially when Good is nowhere to be found or preoccupied with its hierarchies and hypocrisies. Grittiness coexists with what the otherwise unsmitten science fiction writer Damon Knight conceded was “dreamdust sparkle.”

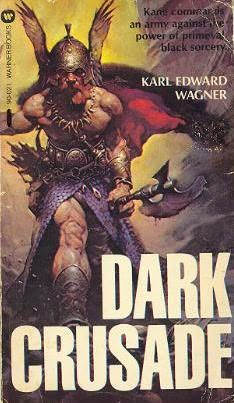

Our final witness, Karl Edward Wagner, identifies sword-and-sorcery as “a fascinating synthesis of horror, adventure, and imagination, ” displayed to best effect in “a universe in which magic works and an individual may kill according to his personal code.” The fact that horror is listed first in Wagner’s “fascinating synthesis” and his pointed mention of code-governed killing are only to be expected from the creator of that First Manslayer and Eden escapee Kane, who wanders accursedly through the collections Death Angel’s Shadow and Night Winds and the novels Bloodstone, Darkness Weaves, and Dark Crusade. Although Wagner objected to the term sword-and-sorcery, which he believed to be belittling, he also insisted, crucially, that the subgenre “can command the reader’s attention on multiple levels of enjoyment.” The fact that the levels of enjoyment do indeed have the potential to be multiple has been lost on too many other commentators.

Having been careful not to lock ourselves into a single definition or a set of rules begging for exceptions to show up and show them up, we are now in a position to borrow Fritz Leiber’s imagery of “wide fringes of borderland” and conceive of sword-and-sorcery as a border kingdom ruthlessly carved out of the frontier provinces of fantasy, horror, and historical adventure fiction. In The Hour of the Dragon the conspirator Orastes assesses the Cimmerian who rules Aquilonia as ripe for overthrowing: “He is not part of a dynasty, but only a lone adventurer.” Steadfast vassal Servius Galannus reinforces the point by telling Conan “You have no heir to take the crown.”

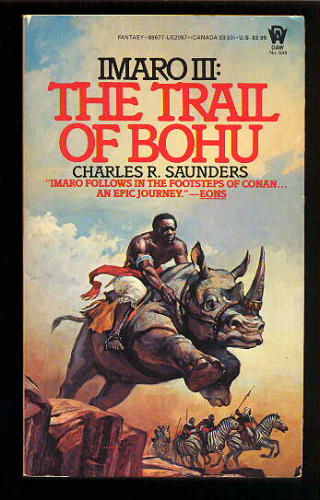

But Howard, unlike Conan at the time of HOTD, was a dynasty-founder in the border kingdom he’d created. Heirs duly appeared to take his crown and preserve a succession, albeit one based upon worth rather than birth. After a few Weird Tales pretenders to the throne like Clifford Ball and Henry Kuttner, there arrived in Leiber a successor who would rule with a more elegant roguishness than Howard’s for many years. Michael Moorcock, a prince from across the water who came close to mastering the kingdom if not his own ambivalence, dominated the subsequent interregnum with his Eternal Champion avatars Elric of Melniboné, Dorian Hawkmoon, and Corum Jhaelen Irsai, and then the young march-wardens Karl Edward Wagner, Charles R. Saunders (Imaro, The Quest for Cush, and The Trail of Bohu) and David C. Smith (Oron, The Sorcerer’s Shadow, Mosutha’s Magic) seized new territory in audacious campaigns on multiple fronts.

Unfortunately, their conquests were not followed by consolidation; venturesome characters like Kane, Imaro, and Smith’s Oron never quite gained their creators the resources and recognition they had more than earned. Instead, for sword-and-sorcery by the early 1980s, the best of times commercially was too often the worst of times creatively. Drugstore racks and bookstore displays were a Muscle Beach of Braks, Jariks, Jandars, Kandars, Kothars, Thongors, Wandors, and Odans, but the formulaic and the forgettable held sway — too many statues came to life (often more convincingly than the heroes they menaced), too many tentacles groped to no great effect, too many graves surrendered skeletons that clattered into combat, too many towers proved to contain nothing as memorable as the secret of “The Tower of the Elephant” but merely confirmation of the author’s inventive shortfall. Iconoclasm, which did exist, was obscured by an iconography that begged to be trivialized or burlesqued, and was, in the lumbering movies of the period. The “signature” sword-and-sorcery film, Conan the Barbarian, was more like a forged endorsement due to its director’s spectacular lack of interest in, or understanding of, the subgenre.

But to impose a 70s boom/80s bust storyline is to oversimplify. 1984 can be described as a tale of two nadirs: the cinematic nadir of Conan the Destroyer and the Nadir, the continent-overrunning crypto-Mongol nomads of David Gemmell’s Legend. That first of 30 heroic fantasy novels was given a U.S. tryout as Against the Horde (1988), but until the late 90s Americans were mostly denied what critic John Clute singled out as an “ability to press ahead with revelation and action at a pace whose intensity can seem at times almost surreal” (Clute’s words call to mind an earlier, Texan heroic fantasist about whose work Gemmell, who never ceased remembering the Alamo, was unfailingly complimentary). The circumstances that produced Legend (1984) have become as legendary as the adamant non-surrender of the Nadir-engulfed defenders of Dros Delnoch within the book’s pages. Misdiagnosed as being terminally ill, Gemmell opted to work out his feelings about the death sentence in a manuscript. His determination to stare down his own mortality and fascination with few-against-many clashes like Thermopylae and Rorke’s Drift inspired a siege as epic as, and more episode-rich than, Tolkien’s Helm’s Deep and Minas Tirith or Karl Edward Wagner’s melding of Troy and Verdun in his harrowing Night Winds tale “Lynortis Reprise.”

Druss, a.k.a the Captain of the Axe or Deathwalker, made his debut and met his demise in Legend, but prequels appeared by genuinely popular demand until Gemmell’s tale-telling was cut short in mid-career by his death on July 28, 2006. Druss emerged from a blood-red gene pool; his father having recoiled from the carnage his grandfather reveled in, and in the axeman’s relationship with his weapon Snaga as in that of Elric and Stormbringer, the question of who wields whom remains unsettled.

Right on up through the decidedly non-Virgilian Aeneas of Lord of the Silver Bow (2005), who burns captured Mycenaean pirates alive in a campaign on “the Great Green” just prior to the outbreak of the Trojan War, Gemmell depicted men who cannot escape from violence and indeed have often previously escaped into violence. He drew upon past stints as a silver-tongued rather than iron-fisted bouncer, day laborer, and investigative journalist; not since Howard famously built Conan from “the dominant characteristics of various prize-fighters, gunmen, bootleggers, oilfield bullies, gamblers, and honest workmen” has a heroic fantasist watched how certain men live, and live with themselves, so attentively.

Besides Druss, who partners Skilgannon the Damned, another killer of killers hounded by memories as well as unrelenting pursuers, in White Wolf (2003) and The Swords of Night and Day (2004), Gemmell’s creations include assassin nonpareil Waylander and Jon Shannow, the Jerusalem Man of Wolf in Shadow (1987), The Last Guardian (1989), and Bloodstone (1994), a postapocalyptic paladin whose sixgun-and-sorcery adventures are more efficiently told but just as Eastwoodian as those of Stephen King’s Roland the Last Gunslinger. He devised a Matter of Britain variant, Utherian fantasy, with 2 novels of the embattled Pendragon, Ghost King (1988), and Last Sword of Power (1989). The Sword in the Storm (1998) and Midnight Falcon (1999) take up the old quarrel of William Morris (in The House of the Wolfings), Talbot Mundy (in the Tros of Samothrace series), and Robert E. Howard with Rome as Connavar the Demonblade and the Keltoi tribes he unites are caught between the all-annexing legions of imperial Stone and the longships of Vars sea wolves.

Ravenheart (2001) and Stormrider (2002) revisit Connavar’s kinsmen in a later, Rob Roy-esque age in which “Varlish” oppressors strive to break the spirit and erase the culture of the proud highlanders. Gemmell’s own blood boasted a touch of tartan, and in other novels (Morningstar, Hawk Eternal) indomitable clansmen also preserve their cattle-thieving, claymore-brandishing ways in defiance of overweening outsiders. No higher praise exists in his work than to say of someone “He’s a man to walk the mountains with.”

Gemmell’s weaknesses? The demons that trouble his characters from within are more convincing than those that do so from without, and he was always more interested in monstrous deeds than monstrous beings, although Dark Moon (1996), Winter Warriors (1997), and Hero in the Shadows (2000) escalated the efforts of pre-human or inhuman forces to regain hegemony. A preoccupation with redemption and expiation as bad men manage to come to good ends occasionally risked sententiousness. But quantity never endangered quality, despite the staggering productivity that made Gemmell a bestselling heroic fantasist for 3 consecutive decades. And his Troy sequence, consisting of Lord of the Silver Bow, Shield of Thunder (2006), and Fall of Kings (2007), the last of which was completed, in a collaboration in no way posthumous because rooted in a shared life, by Stella Gemmell, demonstrated a probability-defying growth spurt in terms of ambition and audacity. Imagine challenging none other than Homer in a passage at arms with bronze blades, and not embarrassing oneself. . .

Gemmell has been denied a chance to challenge Fritz Leiber’s half-century of work in the subgenre, and it is unlikely that the latter’s genre-flouting coup of 1970 will ever be matched. That year his “Ill Met in Lankhmar,” a novella about the newly-teamed Fafhrd and the Mouser’s loss of, if not innocence then at least youthful insouciance, won science fiction’s Hugo and Nebula Awards. By The Knight and Knave of Swords (1988), later incorporated in Farewell to Lankhmar (1998), the 2 “dubious heroes and whimsical scoundrels” are balancing on the cold knife’s-edge between the late autumn and early winter of their careers. Repairing to Rime Isle, which is reminiscent of a post-saga Iceland, they resolve (mostly) to accentuate the merchant half of being merchant-adventurers, and Leiber cannily folds predictable reader resentment of their we’ll-go-much-less-a-roving melancholy into Knight and Knave. At one point Fafhrd is “perversely lonely for Lankhmar with its wizards and criminous folks, its smokes (so different from this bracing northern sea air) and sleazy grandeurs,” while the Mouser admits to being “tired of killing.” But more than winding down and settling in is going on; the showpiece novella “The Mouser Goes Below,” in which the principal battlefield is the boudoir, renders explicit the extent to which the Small Gray One might have been a much darker shade of gray had he never met up with his noticeably better half Fafhrd.

Another veteran was reactivated as Michael Moorcock summoned the old magic in The Fortress of the Pearl (1989), which recounts Elric’s crimson reckoning with Quarzhasaat, a desert city unwise enough to challenge his ancestors. The Revenge of the Rose (1991) initially sustains the momentum as the Prince of Ruins salvages a symbiosis with a relict Melnibonéan dragon graceful as “a wind-dancing kestrel” and has an Elsinorean encounter with the ghost of his royal father Sadric. But Rose progresses by digressing, a trend that escalates in The Dreamthief’s Daughter (2001), The Skrayling Tree (2003), and The White Wolf’s Son (2005). Not-quite-invisible quotation marks seem to be flapping their batwings around characters and events, while the Moorcockian multiverse is now a wilderness of mirrors, reflections gesturing to reflections with no underlying realities in sight. The recent Elric is himself more transparent than albino; when he has appeared, the suspicion has been that a contractual obligation is being wanly honored, so it is a pleasure to report that the new adventure “Black Petals” (Weird Tales March/April 2008) is a gratifying throwback.

An expansive rather than contractive or constricted take on what is heroic fantasy and what isn’t permits us to claim works by Michael Shea and Tanith Lee, writers at home throughout the fantastic genres. Shea’s Nifft the Lean (1982), The Mines of Behemoth (1997) and The A’rak (2000) show again and again that he is qualified to join Dante and Bosch in brainstorming Infernos, and his at-times feline sensibility recalls the claw-tipped caresses of Clark Ashton Smith and Jack Vance.

Lee launched sword-and-sorcery sequences that exceeded, and subverted, readers’ expectations with The Birthgrave (1975) and The Storm Lord (1976), and whenever she returns to heroic fantasy, she functions as a coldly candid wind blowing up the subgenre’s kilt, or a source of searing scrutiny in which anything facile shrivels and the fulfillment of such wishes as are fulfilled can startle those who do the wishing. That is the case with Cast a Bright Shadow (2004) , Here in Cold Hell (2005), and No Flame but Mine (2007), the three parts of her Lionwolf Trilogy set in a winter-entranced Ultima Thule, northern without being Norse. Barbarians ride snow-mammoths and fish-horses, an “icon of bronze and fire” leads a tribal Gullahammer, a “hammer of a million heads,” against fading cities, pseudo-saurian parasites scavenge in the skin-folds of a continent-sized whale, and enmity is sworn in a fell afterworld “till time itself is dead and rotting in some hell.”

The second half of the 1980s saw a shamrock-trampling stampede of cheapjack Celticism, to which the work of the Australian [redacted] was a rebuke and a reminder of what could be done with Northern European themes. His 5 Bard novels, set on the same seas and shores frequented by Cormac Mac Art and Wulfhere the Skull-splitter, play with Howard’s piratical pairings of not only the Gael and Dane but also Conan and Bêlit in the amour fou of harpist Felimid mac Fal and reaver Gudrun Blackhair. [redacted] commuted surefootedly between Tir Nan Og, Camelot, and Valhalla. for three books, and although Felimid’s artistic prowess never prevents him from also making his sword sing, his humor and humane tendencies confer upon him a unique status, half-in and half-out of the Celtic and Germanic warrior ethos. Then came the fourth Felimid novel, Raven’s Gathering (1987), which is the standout. Gudrun’s Valkyrie veneer is sorely tried as Odin and rival sea-wolves turn on her in a Ragnarok-writ-small that vies with Poul Anderson’s reconstruction of Hrolf Kraki’s Saga (1973) as an evocation of what Tolkien called the Old North’s “potent but terrible solution in naked will and courage” to the inevitable victory of dark powers.

The same ethos gleams a chilly blue in Stephan Grundy’s Rhinegold (1994), dedicated to Richard Wagner and Tolkien but sure to delight many sword-and-sorcery devotees with its wargs and Walsings, hordes and hoards. As for Anderson himself, War of the Gods (1997) reaffirmed the stature The Broken Sword (1954) had won him as an honorary frost giant, the greatest American exponent of “the Northern thing.” The primal Midgard of War still reels from the repercussions of the war between the Æsir and Vanir as Hadding of the Skjoldungs rises to kingship in northlands not wholly relinquished by jotuns, nicors, trolls, night-gangers, and land-wights.

The ever-darker delights of the 1990s, which often seemed likely to cause a scarcity of black ink, were heralded by Glen Cook’s The Tower of Fear (1989), in which the city of Qushmarrah, suggestive of Punic Carthage and Roman-garrisoned Jerusalem, seethes with necromancy and incipient intifada under its Herodian occupiers. Darrell Schweitzer’s The White Isle (revised 1989) sends Prince Evnos of Iankoros on an errand like that of Orpheus to a caperingly cruel underworld. The even more harrowing second half of the novel is given over to a war of wills between father and daughter on Iankoros, an island turned death’s other kingdom. In Australian Andrew Whitmore’s The Fortress of Eternity (1990) characters enduring the “agonizing rack of being” race to forestall a malign theophany in a world “dwelling at the gutter-end of Time.” A forest kingdom’s rangers and outlaws in Simon Green’s Down Among the Dead Men (1993) are drawn to a border fort beneath which something older and fouler than any demon dreams unspeakably. The ensuing pyrotechnics avoid the facetiousness with which Green has been known to self-sabotage his many other swashbucklers and space operas.

Generous helpings of horror make the heroism in heroic fantasy more heroic, and who better to supply them than a modern master like Ramsey Campbell? Far Away and Never (1996) collects his 1970s sword-and-sorcery, including 4 stories of Ryre, in the author’s words “as much of [a hero] as I could believe in,” and a sole exemplar of initiative, however mercenary, in sun-stunned, dust-choked regions of squalor and torpor where slavering mouths and vampiric wings are all-but-disembodied but no less voracious for it.

Engor’s Sword Arm (1997), an expanded version of one of David C. Smith’s Attluma stories, is a sort of epilogue or afterword to the earliest history of humankind; the gods are dead but the pretense that men rule men is also dying. Smith sends the central tableau of the subgenre, the eventual confrontation between swordsman and sorcerer, spinning off into the Outer Dark, which is exactly where the major weird fiction event of the late 1990s, Brian McNaughton’s Throne of Bones (1997), made its lair. The linked stories of Throne are mostly a danse macabre of sportive ghouls, but “The Return of Liron Wolfbaiter” features a Fomorian Guardsman named Crondard Sleith whose misadventures after killing his captain might have had Howard and Leiber smiling while swallowing hard: “The blood of demon-haunted barbarians screamed that he had blundered into a blackness deeper than the night beyond a northern hearth.”

Interviewed by Gabriel Chouinard in 2001, Matthew Woodring Stover said of his fiction “They used to call it swords and sorcery. . .I really, truly, profoundly believe that swords and sorcery (fantasy, SF, whatever) ought to be more than just junk food.” Stover’s Iron Dawn (1997) introduces Barra, a Pictish warrior-woman who trained with the bulldancers of Knossos and soldiered as one of the Pharoah’s Shardana. In a nod to Leiber’s only non-Nehwonian Fahrd/Mouser novella “Adept’s Gambit,” Barra is based in Tyre, but hers is the earlier Tyre of the late Bronze Age; both Iron Dawn and its sequel Jericho Moon (1998) are awash in empty-eyed veterans of the Trojan War who have never really left the plains before Priam’s city. In the second book Barra throws in with the Jebusite defenders of what is not yet Jerusalem against the Habiru tribes led by the tormented Joshua, “a man used hard in the service of his god.” We learn why the ruins of the fallen Jericho are no place for the living and are treated to the most all-out assault on Yahwist or Jehovan omnipotence since Harlan Ellison’s “The Deathbird.” All of Stover’s heroic fantasies offer fight scenes of such crippling power that they risk hospitalizing incautious readers: the original, transcendently apposite title of Heroes Die (1999) was Acts of Violence, described by Stover as “a piece of violent entertainment that is a meditation on violent entertainment.” In this novel sword-and-sorcery, as it is enacted by both the natives of, and Earthly “Aktiri” transported to, the transdimensional Overworld, is the opiate, the Soma, of the masses back home, the bread and circuses that keep consumers consuming. Peter Beagle’s well-known words about Tolkien — “Let us now praise the colonizers of dreams” — start to seem very sinister indeed the deeper one reads in Heroes Die and its even more unsparing sequels The Blade of Tyshalle (2001) and Caine Black Knife (2008).

It might seem strange to speak of the increasing militarization of a subgenre largely built on the Nemedian invasion of Aquilonia, Poul Anderson’s great northern war between elves and trolls in The Broken Sword, and the titular event of Wagner’s Dark Crusade, but vast campaigns and defenses-in-depth have all but driven out the incidents and vignettes of yore. Fewer barbarians steal into temples to steal from sorcerers and villages see fewer wanderers who save maidens from being sacrificed to the local godling. Glen Cook told Jeff VanderMeer that “The conflict between fantasy and real medieval warfare is stark” in a 2005 interview, but combined-arms operations relying on swords and sorcery have become a staple not only in Cook’s beloved Black Company series but also in Steven Erikson’s Cook-endorsed Malazan Book of the Fallen sequence, which applies the Canadian author’s training as an archaeologist and anthropologist to hailstorms of falling empires and battles as seismic as the grindings of tectonic plates. The Malazan novels thus far are Gardens of the Moon (1999), Deadhouse Gates (2000), Memories of Ice (2001), House of Chains (2002), Midnight Tides (2004), The Bonehunters (2006), Reaper’s Gale (2007), and Toll the Hounds (2008).

The outputs of Gemmell, Stover, Cook, and especially Erikson, who threatens the livelihood of doorstop manufacturers, reflect the way market realities have forced sword-and-sorcery into a dependence on novels that is at variance with its pulp and paperback heritage. Like horror, the subgenre is “at ease in shorter lengths,” as David Pringle once put it, thriving in novellas and novelettes — think “The People of the Black Circle,” “Adept’s Gambit,” or Wagner’s “Raven’s Eyrie” in the Night Winds collection. But with the best of the new swordmasters, the pages turn just as quickly even if there are more of them.

Like Gemmell and Erikson, Northern Ireland’s Paul Kearney has been caught speaking knowledgeably and enthusiastically about Howard’s classic heroic fantasy characters. His The Monarchies of God combines the immemorial power structures honeycombed with shapeshifting infiltrators of “The Shadow Kingdom” and the titanic grudge-match between an onrushing East and an unyielding West of “The Shadow of the Vulture.” The sequence consists of Hawkwood’s Voyage (1995), The Heretic Kings (1996), The Iron Wars (1999), The Second Empire (2000), and Ships From the West (2002). Kearney moved on to The Mark of Ran (2004), and This Forsaken Earth (2006), in which the scion of a pre-human pariah race becomes the most audacious captain of a hidden pirate city, and although that series (the overall title of which is The Sea Beggars) was rudely interrupted by The People of the Green Eyeshade, he is back again with The Ten Thousand (2008), a fantastication of Xenophon’s Anabasis. Kearney’s Normanni-versus-Merduk clash of civilizations in The Monarchies of God, which echoed the Ottoman attempts on Vienna and the Balkan wars of the 1990s, anticipated the barely-disguised crosses and crescents that bludgeon each other in several 21st century series.

Having already courted a fatwa with a secular study of an empire-affrighting Prophet-figure in his The Fire in His Hands (1984) and With Mercy Toward None (1985), Glen Cook further disturbed the “peace” of militant monotheisms with the Instrumentalities of the Night sequence. In leadoff installment The Tyranny of the Night (2005), the Holy Land of a world in which magic is on the wane and fanaticism is on the boil is torn between adherents of a Patriarch and a “Kaif.” More dynastic, schismatic, and chiliastic convulsions followed in Lord of the Silent Kingdom (2007). The Warrior Prophet (2005) and The Thousandfold Thought (2006) the second and third novels of R. Scott Bakker’s Prince of Nothing series, re-dream the First Crusade as we remember it from Harold Lamb’s histories to chronicle a Holy War even more apocalyptically destructive than the real thing.

Encouragingly, revivals have restored some of sword-and-sorcery’s missing — and much-missed — memories. Chaosium’s The Scroll of Thoth: Tales of Simon Magus and the Great Old Ones (1997) did aficionados of Richard Tierney’s studiously syncretic weird fiction an incalculable favor by assembling most of the stories about ex-gladiator and Julio-Claudian bugbear Simon of Gitta in one volume; Wagner’s Kane makes an unbilled guest appearance. Night Shade Books’ A Cruel Wind: A Chronicle of the Dread Empire (2006) gathers the original 3 novels of Glen Cook’s first heroic fantasy sequence: A Shadow of All Night Falling (1979), October’s Baby (1980), and All Darkness Met (1980). A Fortress in Shadow followed in 2007.

Exorcisms and Ecstasies (1997) is a bittersweet assemblage of Wagneriana. The references in its Kane fragment to “the broken ruins of prehuman dream” and the “flaming death of Eden” induce a state of longing on the far side of tantalization as we contemplate all that we will ever read of In the Wake of the Night, sword-and-sorcery’s greatest story never told.

Regrettably, Gods in Darkness: The Complete Novels of Kane (2002) and The Midnight Sun: The Complete Stories of Kane (2003) were indifferently packaged and even more indifferently proofread by Night Shade, publishers who also encouraged, at least initially, Charles R. Saunders to end his premature retirement. His 1970s stories and 1980s novels about Imaro of Nyumbani, the most wounded warrior since Philoctetes, showcased his passion for, and pride in, the vibrance of African history and myth, and also constituted sword-and-sorcery’s most notable attempt at self-correction and slur suppression.

Imaro (2006) enticed with 2 new novellas, but Night Shade lost interest in the Ilyassai hero’s relaunch after The Quest for Cush (2007). Far from concluding that Sisyphus himself would have rejected further efforts to push this particular boulder uphill as pointless, Saunders struck out on his own with Dossouye (2008), which collected his stories of a self-exiled swordswoman positioned against, but separated from, cultures far more exotic yet authenticated than any to be encountered in the adventures of Red Sonja, Raven, or Robin W. Bailey’s Frost. Future self-published volumes will present more Dossouye and both reconceived and never-before-published Imaro material. And Saunders’ comparably gifted contemporary David C. Smith is readying a definitive collection of his hard-to-find tales of Attluma, that primal island continent engulfed not by the oceans but equally all-devouring demonic forces.

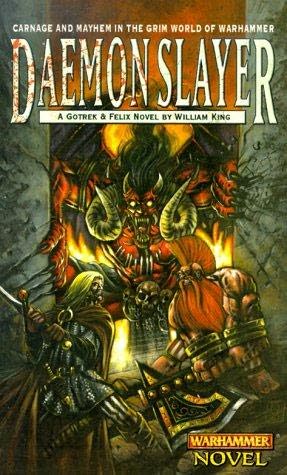

So nowadays a devotion to word-and-sorcery need not entail tomb-robbing and fossil hunting; the subgenre has a presence outside used bookstores and cyber-conclaves of graying fans. Millions of potential readers were exposed to the tried-and-true trappings, at times computer-conjured but acted and directed with more brilliance and bravura than ever before, in Peter Jackson’s LOTR films. Robert E. Howard, the most Howardian Howard ever made available, is back in bookstores courtesy of the Wandering Star team and their Del Rey partners. Bran Mak Morn: The Last King, The Bloody Crown of Conan, The Conquering Sword of Conan, and Kull: Exile of Atlantis are alphabetically adjacent to a warrior-king’s-ransom of Gemmell novels, and within browsing distance of Erikson, Stover, and Kearney. It is only a matter of time until Scott Oden strays from historical adventure with a subgenre contribution hard-hitting enough to put our junior high school English teachers in bodycasts. An up-and-comer who deserves to be singled out is Scotsman William King, another Howard admirer whose rip-roaring Gotrek & Felix novels include Trollslayer (1999), Beastslayer (2001), and Giantslayer (2003). King has also introduced an immediately convincing, classically brooding Highlands swordsman with the not unfamiliar name Kormak.

Heroic fantasy isn’t going anywhere — except forward into a future in which its swords will continue to cut through the clutter and its sorcery will continue to spellbind.