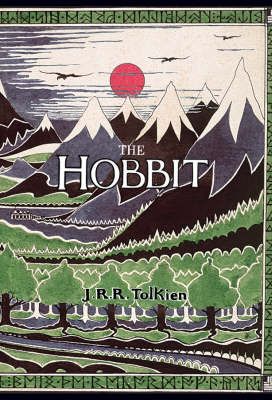

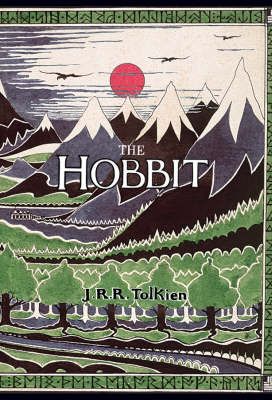

Too many of my waking hours are given over to thinking about the Hobbit films due in December of 2011 and December of 2012; no sooner is my attention directed elsewhere than the voluble and value-adding Guillermo del Toro is interviewed again and — sproing! — my thoughts ricochet back to the movies he’s about to make. After all, it won’t hurt to have something to which I can look forward after moving to a Hooverville and while shuffling along on Hoover leather (The Internet is of course rendering Hoover blankets obsolete). Admittedly my druthers would have been a movie about the wrath of Fëanor, the wanderings of Húrin, the fall of Gondolin, or the last days of Númenor. But any Silmarillion-based movie would be hobbit-free, and hobbits shift units and sell tickets. Me, I tolerate rather than love them, although I would never go as far as Michael Moorcock, who quipped of Sauron, “Anyone who hates hobbits can’t be all bad,” or the younger Charles Saunders, who once expressed (he has since mellowed) a profound relief that there were no black hobbits. Admiration and affection for Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin I have aplenty; I just don’t love hobbits qua hobbits. But many do; adoption agencies that offered hobbit orphans would be forced to hire extra security for crowd control.

In his magisterial two-volume The History of the Hobbit John D. Rateliff backhands “critics who would prefer The Hobbit to conform to and resemble its sequel in every possible detail.” Guilty as charged; I try and mostly succeed in cherishing the book for its own self, and almost fainted when, in the dealers’ room at the 2006 World Fantasy Convention in Austin, I came face to face with a first edition 1937 Hobbit. But reading-sequence is destiny, and I first read the “enchanting prelude” in the spring of 1971, a few weeks after hurtling through The Lord of the Rings. As a result, what really got my pulse pounding like hammers in dwarven smithies were what Tolkien, looking back from the vantage point of LOTR‘s Second Edition, described as “references to the older matter: Elrond, Gondolin, the High-elves, and the orcs, and glimpses that had arisen, unbidden, of things higher or deeper or darker than [The Hobbit‘s] surface: Durin, Moria, Gandalf, the Necromancer, the Ring.” Although not immune to the beguilingly unique properties of The Hobbit, I responded the most to premonitions and foreshadowings of the later work, the design features of the Eohippus from which the later Arabian stallion could be extrapolated. So for me “higher or deeper or darker” is the way to go in the impending movies, because so many millions of filmgoers will plant themselves in multiplex seats as vividly aware of the previously-viewed-even-if-chronologically-“later” Peter Jackson films as I was of the previously-read-although-chronologically-“later” LOTR back in 1971. Some of the posts at Tolkien-oriented and other genre sites reflect apprehension that Guillermo del Toro and Peter Jackson will “spectacularize” or “bombastify” the source material, inflate a children’s classic into a swollen epic, and such protectiveness is laudable, but barring an Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind-style memory-scrub, the audience can’t be made to unsee The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. Ergo higher, deeper, darker.

(Continue reading this post)