Linkage and Thinkage

Friday, November 21, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Howardists’ Howardist Charles Hoffman turns in an Amazonian review of The Collected Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard. He’s none too affrighted by “Rattle of Bones” (for my part I don’t think “Delenda Est” is classifiable as a horror story unless one is on the payroll of the late-period Roman Empire) and sticks up for the excluded “The Hyena,” “Black Wind Blowing,” and especially “The People of the Black Coast.” I tried to push that story hard in a TC essay back in February, but it seems that “People” is a rare blind spot for His Editorial Excellency Rusty Burke; perhaps he’s simply dined too well on too many crabmeat dinners over the years to accept the crustaceans’ oversized and supersapient brethren as a credible threat.

Today is of course Black Friday for those of us who unswooningly prefer the gore-and-gravedirt-reeking, hemoglobin-slurping, food-chain-topping undead of yester-fiction, so it’s great to see Hoffman plugging The Collected Horror Stories at the expense of “contemporary horror…recently dominated by chicks’ overheated erotic fantasies about their imaginary vampire boyfriends.” I don’t think Del Rey did themselves any favors in terms of imprinting a strong visual identity for each REH collection this time, though. Here’s the Greg Staples tentacular spectacular that for months was the front runner for front cover:

Instead they went with this:

Which is a bit too close to this:

Here’s “Hardboiled and Proto-Noir Elements in the Life and Fiction of Robert E. Howard,” an article by Ross E. Lockhart. The “Life” part trots out Howard as Locked-and-Loaded Paranoid (too much Dark Valley Destiny, not enough One Who Walked Alone and Blood & Thunder), but when Lockhart turns to the “Fiction” his focus on “Names in the Black Book” and “Graveyard Rats” is refreshing, and he manages a nifty riff on Steve Harrison as “simultaneously hearkening back as far as Beowulf and yet predicting Mickey Spillane’s bare-fisted brawler Mike Hammer and Frank Miller’s Marv.”

Over at The Silver Key, TC contributor Brian Murphy felt like a drive-by victim when he turned his drive-time over to an audiobook version of Burroughs’ The Land that Time Forgot. Directing enough torpedos at Caspak’s fault-lines to sink the whole endeavor, Brian also gratifyingly lobbies for the enforcement of Sturgeon’s Law in a sector of pop culture too often deemed extra-jurisdictional:

…I’ve noticed that pulp often gets a free pass from its advocates. Fans will leap to the defense of poorly plotted, boring, or otherwise not well-written stories and pulp-inspired films with a simple, “well, it’s pulp”–as if this fact somehow makes the genre above criticism.

Amen. To react to any story as would Twilight‘s overheated Bella when approached by the underheated Edward just because the story in question was available on cheap paper at newstands during the decades when men wore hats is to disrespect the genuine greats of the pulp era.

An Ain’t It Cool News contributor had the chance to hobnob with Guillermo del Toro, whose song is still one of (Lovecraftian/Antarctic) Ice as well as (Tolkienian/dragon-) Fire. The director had this to say about his At the Mountains of Madness project:

I think that Lovecraft needs to be given the A-plus treatment. What he is in fiction in my mind…he’s the highest caliber of fiction. And he needs to be on film. And so far the only properties that are not Lovecraft but Lovecraftian are Alien by Ridley Scott and The Thing by John Carpenter…I am a massive fan of Re-Animator but the cosmic side of Lovecraft needs a big budget.

It might be possible to argue that The H.P. Lovecraft Society’s “Mythoscoped” The Call of Cthulhu proved otherwise, but At the Mountains is certainly far more “cosmic” than the earlier story.

The DashPunk site offers more from del Toro.

GDT is only the second best thing to happen to The Hobbit recently. The best is John D. Rateliff, who has changed, has upgraded the way Bilbo’s story is read with his Mr. Baggins and The Return to Bag End. I suffer from whatever the equivalent of illiteracy and innumeracy is when it comes to gaming, so when I read Bill Cavalier’s “The Other REH Days in TC V4n5 (October 2007), I was baffled by the Gygaxian attempt to launder Tolkien right the hell out of the DNA of D & D. Now Rateliff, a games editor and TSR vet, has served up a four-part “Brief History of Tolkien RPGS,” in the first installment of which he addresses exactly that point:

The reasons for this disparagement of Tolkien’s influence on D&D, and thus ALL roleplaying games, are I think twofold. First, there’s the simple fact that Tolkien’s innovations are so great that they have, ironically, come to be considered “generic”. In fact, they only appear that way because the genre of Modern Fantasy is something Tolkien himself largely created: he is the exemplar that defines the category. The very idea of a player character party — a group of diverse individuals of differing races with differing talents and specialties who set off on an adventure together — is a uniquely Tolkienian innovation, unprecedented in earlier fantasy, where we either have a hero, or a hero & a sidekick. In other words, Tolkien influenced fantasy and gaming so profoundly that we take his imprint on other authors for granted. His impact has become invisible — just look how many people spell “elves” and “dwarves” with a ‘v’ rather than elfs and dwarfs: elves may be partly due to Dunsany, though I doubt this, but dwarves is Tolkien’s invention, which others use without even recognizing their indebtedness.

Second, there was a deliberate attempt in later years by Gygax and others, continuing to the present day, to play down Tolkien’s influence, most notoriously in Gygax’s famous editorial from the March 1985 issue of Dragon magazine (issue #95, pages 12¬–13). Titled “The influence of J. R. R. Tolkien on the D&D® and AD&D® games: Why Middle Earth is not part of the game world”, it argues that Tolkien had NO discernable influence on the development of D&D, aside from a few surface similarities based on Gygax’s drawing on the same sort of sources as Tolkien himself had used.

Now, there are three theories regarding this claim, which was met with incredulity at the time and more or less universally dismissed ever since, being belied by the evidence both past and present. The first is what we might call the cocaine theory, the widespread belief that years of rumored drug abuse during E. Gary Gygax’s time heading up TSR’s Hollywood branch had addled his brain. The second is that Gygax simply forgot by the mid-eighties how he’d created the game in the early seventies; certainly his story changed a number of times over the years, and the general trend of those changes is to shift credit away from others (e.g., Arneson) and onto himself. So maybe he simply resented sharing credit with JRRT. The third is, in a word, lawyers, and a salutary fear of lawsuits if any good case could be made for D&D’s debt to Tolkien’s work. And, as we’ll see, he had excellent reason based on personal experience to believe this was a very real threat, which might explain why he was so adamant about denying any Tolkien influence in his 1985 piece, which freely admits to influence from a number of other lesser writers.

For, no matter how much Gygax might have later denied it, Tolkien’s fingerprints are all over original D&D…

Scott Oden is considering a blend of Greek and Germanic myth and “Worms of the Earth” for his non-Morgothian Orcs, possibly enslaving them in Tartarus as “punishment for some transgression such as fighting on the wrong side in the Titanomachy.”

Just to encounter the Titanomachy in a blog-post made my day. While the Professor was mostly accurate in “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” about how the northern mythic imagination “has power, as it were, to revive its spirit even in our own times,” as opposed to “the older southern imagination [which] has faded for ever into literary ornament,” I’ve always made an exception for mercilessly modern plays like Sartre’s The Flies, Anouilh’s Antigone, and Giradoux’s Tiger at the Gates, while also thinking that a harvest of nightmares could be had from the dark hinterland of Greek mythology, when the Erinyes and even more disturbing entities policed their airspace like Nazgûl. The Hekatonkheires, the hundred-armed Olympus-stormers like Briareos, really deserve an apocalyptic revival, and it’s cool to find Scott mentioning beings like Phorcys and Ceto.

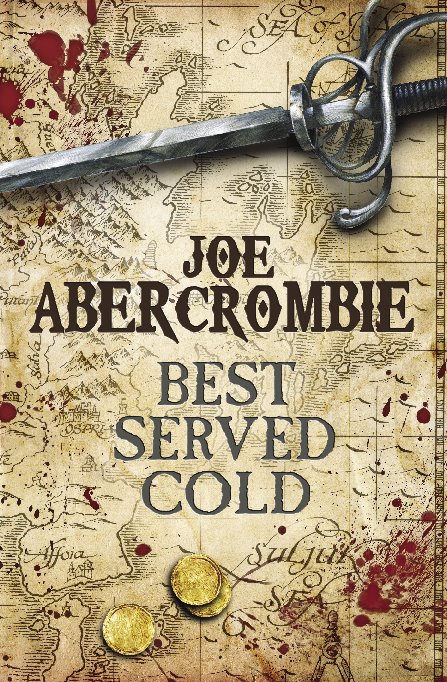

Joe Abercrombie has released the copy and artwork for Best Served Cold, his 2009 bonanza de badasserie:

There have been nineteen years of blood. The ruthless Grand Duke Orso is locked in a vicious struggle with the squabbling League of Eight, and between them they have bled the land white. While armies march, heads roll and cities burn, behind the scenes bankers, priests and older, darker powers play a deadly game to choose who will be king.

War may be hell but for Monza Murcatto, the Snake of Talins, the most feared and famous mercenary in Duke Orso’s employ, it’s a damn good way of making money too. Her victories have made her popular – a shade too popular for her employer’s taste. Betrayed, thrown down a mountain and left for dead, Murcatto’s reward is a broken body and a burning hunger for vengeance. Whatever the cost, seven men must die.

Her allies include Styria’s least reliable drunkard, Styria’s most treacherous poisoner, a mass-murderer obsessed with numbers and a Northman who just wants to do the right thing. Her enemies number the better half of the nation. And that’s all before the most dangerous man in the world is dispatched to hunt her down and finish the job Duke Orso started…

Springtime in Styria. And that means revenge.

“Seven men must die” — an allusion to the Budd Boetticher/Randolph Scott classic Seven Men from Now? Let’s hope so.

Returning to Howard’s home-away-from-Cross Plains Del Rey Books, the back cover of Matthew Woodring Stover’s Abercrombie-esque (or is the Briton Stover-esque?) new non-prisoner-taker Caine Black Knife quotes fantasist Christopher Rowley blurbage for the first Caine demolition derby Heroes Die: “The wildest sword and sorcery adventuring since Robert E. Howard’s mighty Cimmerian laid down his sword.” A nice piece of found cross-promotion for the publisher, and the very words “sword and sorcery” had me reflecting about the present-day Ballantine/Del Rey, shelter from the not-in-print storm for Stover, for Howard, and for Michael Moorcock’s generously conceived Melnibonean last will and testament, versus the House of Ill Repute That Judy-Lynn and Lester del Rey Built. As master Tolkienist and arch-anthologist Douglas A. Anderson tells it in his essay “The Mainstreaming of Fantasy and the Legacy of The Lord of the Rings”

These two people deserve a large share of the credit –or the blame –for what happened afterwards to fantasy.

Both of the del Reys were decidedly old-fashioned in their tastes, and when Judy-Lynn del Rey, soon after taking over at Ballantine, was accused of trying to set science fiction back thirty years, she didn’t deny it. Similarly, Lester del Rey, at a convention in early 1975, attempted to define what he wanted as a fantasy editor. He was asked: would he publish a latter-day ernest Bramah (author of the Kai Lung stories, which had been republished in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series). “No, absolutely not,” he replied. What about Dunsany? “I would tell him that he didn’t need all that fancy style to tell a good story.” Basically, del Rey wanted plot and little else. The critic Darrell Schweitzer has described him as “purely a pulp editor, who saw fiction as product,” who “had no artistic pretensions at all” and who represented “that Depression-era, writer-as-working-stiff attitude at its very worst.”

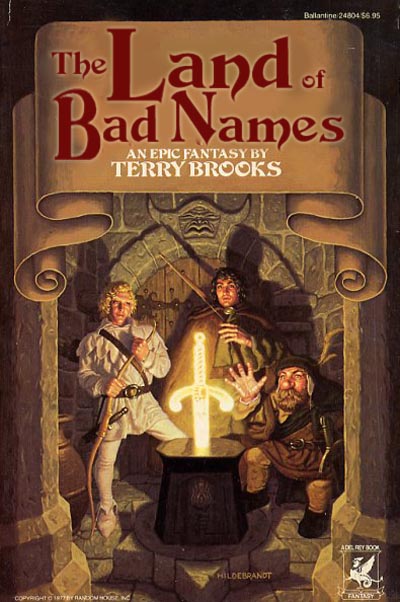

The del Reys took the view that fantasy, long a very small portion of overall fiction sales, could be a real mainstream success if packaged and promoted properly. Two authors were pulled out of the slush pile to prove their theory. The first was Terry Brooks, who had submitted a slavish imitation of The Lord of the Rings under the title The Sword of Shannara. Published in April of 1977, the del Reys added some hyperbole to the cover some hyperbole of a kind that is now so commonplace as to be meaningless: “For all those who have been looking for something to read since The Lord of the Rings.”

Après Brooks, the derivative deluge (Anderson’s second del Rey-discovered author is Stephen R. Donaldson, for me a different case in that the first three Thomas Covenant novels, although tough going at times, at least entered into a dialogue with JRRT’s work rather than robo-lobotomizedly reciting it back). The Brooksian indebtedness was so blatant as to prompt Lin Carter, otherwise a tireless abuser of the sincerest-form-of-flattery defense, to seize the moral high ground for once in his career. Given Ballantine’s windfall from the post-piracy LOTR paperbacks, it’s actually amazing it took 12 years for slush pile monsters to emerge. Of course by 1977 the perfect illustrators were available to smear lipstick on the Shannara warthog; just as the Howard/Frazetta encounter was a meeting of minds and painterly visions, it can’t be denied that Terry Brooks and the Brothers Hildebrandt met on the same plane, although in the latter case it was an how-low-can-you-go declivity.

(Truth-in-advertising mock-cover courtesy of mightygodking.com)

Obviously organizations and companies aren’t people and can’t really atone or extend compensation for past misdeeds, but it’s fun to regard the Del Rey Howard and Elric series as a kind of weregild.