“The High-Spired Splendidness of Old”

Friday, October 17, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Then suddenly fire burst from the Meneltarma, and there came a mighty wind and a tumult of the earth, and the sky reeled, and the hills slid, and Númenor went down into the sea, with all its children and its wives and its maidens and its ladies proud; and all its gardens and its halls and its towers, its tombs and its riches, and its jewels and its webs and its things painted and carven, and its laughter and its mirth and its music, its wisdom and its lore: they vanished for ever.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Akallabêth

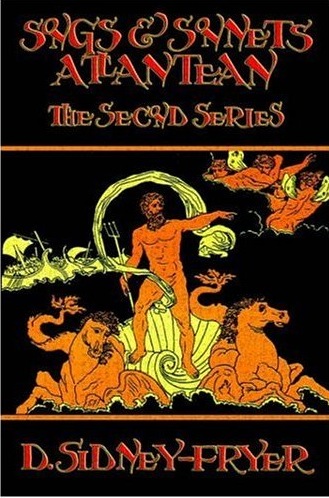

Atlantology, which boasts a Donnelly and a Donovan, is also blessed with a Donald, Donald Sidney-Fryer. Cimmerian readers know him as one of the journal’s triumvirate of poets laureate alongside Richard Tierney and Darrell Schweitzer, a translator, and an essayist who won a 2008 Hyrkanian Award for his “Robert E. Howard: Epic Poet in Prose.” Students of weird fiction know him as a contributor to The Dark Barbarian, the editor of the Timescape Clark Ashton Smith collections The City of the Singing Flame, The Last Incantation, and The Monster of the Prophecy, and the author of The Sorcerer Departs: Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961), the founding document of Klarkashtonian Studies. His website heralds him as “the Last of the Courtly Poets & Northern California’s Only Neo-Elizabethan Poet-Entertainer.” And The Atlantis Fragments, which collects Mr. Sidney-Fryer’s three sets of Songs and Sonnets Atlantean, confirms that he is a direct descendant of mythohistorical figures like Atlas I, called Pharanomion (“the founder”, the Northron-harried Poseidon II, and Atlantarion the poet-king.

Mr. Sidney-Fryer’s “Brave World Old and New: The Atlantis Theme in the Poetry and Fiction of Clark Ashton Smith,” is one of the standout essays in The Freedom of Fantasic Things: Selected Criticism on Clark Ashton Smith (2006), invoking as it does “the rare possibilities for splendor and glamour that this Platonic neo-topia proffers to the original poet.” To the credit of Hippocampus Press, they’ve beautifully packaged the splendor and glamour in a book illustrated by Lance Alexander and William Boddy that deserves to ride out whatever Great Cataclysm awaits our own civilization. As for an “original poet,” of those sub-created by master-poet/poet-master DSF we have a passel, chiefly Allathurion and Atlantarion, as filtered through the Breton Michel de Labretagne (born, significantly, in 1493, the year after we-know-who sailed the ocean blue), who enjoyed access to primary source the Codex Atlanteanus.

1971’s first Songs and Sonnets Atlantean came a year too late for excerpting in Lin Carter’s wondrous anthology The Magic of Atlantis but equipped with an introduction and Notes by “contemporary Atlantologist Dr. Ibid M. Andor” Although something about the good doctor’s monicker fails to inspire confidence, he turns out to be a far more stable scholar than, say, Charles Kinbote, the intrusive editor/annotator of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, and an invaluable tour guide all across “the dominion of many waters embodied in the Empire of Atlantis.” Having sought, in a piece called “Green Roaring Tides of the Atlantean Sea: Kull’s Emerald Epic” in REH: Two-Gun Raconteur #10, to emphasize how many Atlantis-motifs found their way into even the “mainland” or “inland” Kull stories, I stand convicted of eating this subject matter up with an orichalcum spoon, so please be forewarned: This review, she will gush.

Perhaps the choice of The Atlantis Fragments as a title contains a mild irony in that for the culturally literate reader, the very word “fragments” is a mnemonic hyperlink to Eliot’s well-known line in The Waste Land: These fragments I have shored against my ruin. But then The Waste Land, although a rider on the storm of Modernism that engulfed DSF’s Atlantis of Romantic poetry, is also itself a post-cataclysmic effort of sorts. In any event, fragments are what we have to work with courtesy of Messrs. Labretagne and Sidney-Fryer, scattered shards from which we are left to reconstruct the shattered urn. DSF alludes in passing to events that could justify a dozen heroic fantasy novels, all of them better than de Camp and Carter’s Atlanto-Antillian letdown Conan of the Isles, as when child-monarch Poseidon II escapes the fall of Atlantis the city to “the Northkings,” and establishes a refuge in Poseidonis, or we learn that at the time of Atlantean settlement “during the reign of Poseidon III, the great Antillian empire had long since disintegrated into divers rival territories, the island abounded with jaguars, and the semi-tropical jungles had grown up over the ruins of the old abandoned Antillian capital Quoätzl.” We glimpse the parapets of Apenderragon, the Great Watchtower of the Atlanteans in southwest Wales, and the post-Hyperborean ice-realm of Mhu Thulan is explored in “Beyond Ultima Thule.”

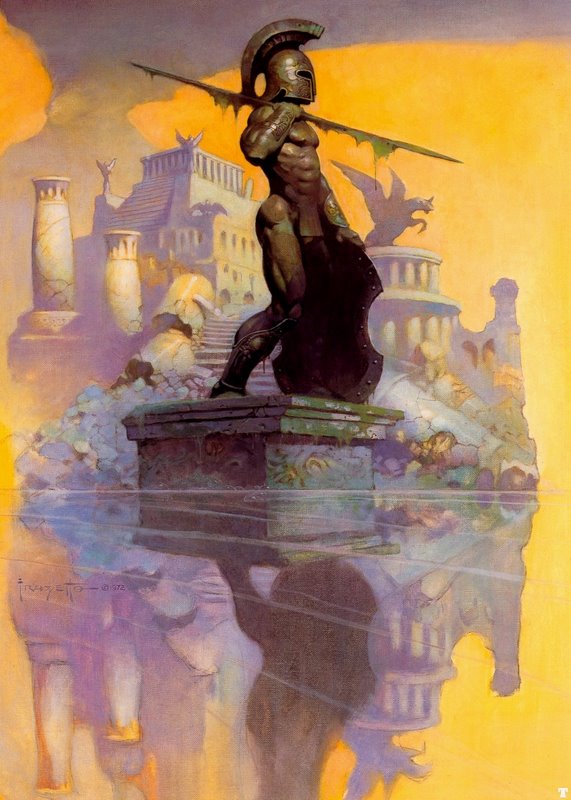

Although we hear tell of a (Plato’s Critias-derived) “Battle Before Athens, which destroyed most of the Pan-Atlantean royalty together with the highest nobility,” this is an aesthete’s Atlantis; the focus is on empire-gilding rather than empire-building. The waves that wash over the doomed empire also wash it clean in a sense, and we witness no cetacean-cowing armada being launched against the pre-Bronze Age cultures of the Mediterranean, nor is any delusional theophany proclaimed by a jumped-up god-king. “Virtually all Atlanteans, especially the young people, were singers and either musicians or poets, or both,” Dr. Andor tells us, and in their company it behooves us to sip pomegranate juice from jeweled chalices, stop and smell the asphodels, admire the supple surety of Antillian jaguars hunting by night. For pre-diluvian action/adventure we must look rather to C. J. Cutliffe Hyne’s The Lost Continent or Lin Carter’s The Black Star, that rare occasion where the author did not disgrace the Frazetta cover he lucked into.

The songs and sonnets never lose track of the forces, not all of them liquid, that threaten “to drown the fires of love, of life, and all of light.” In his introduction Brian Stableford writes “When [Sidney-Fryer] moves from actual to metaphorical oceans, as he often does, it is to cast himself adrift in a dark sea of cosmic space that makes reefs and islets of whole worlds.” And yet despite the perspective-alteration enforced by cosmicism, DSF is immersed in CAS, but never submerged; his is a kindlier, courtlier temperament. The characters of The Atlantean Fragments usually come to good rhymes rather than bad ends.

To be in possession of one of the 300 copies of this book is to hold the product of labors (of love, it is to be hoped) that lasted from March of 1961 through the summer of 2007, more than 45 years of seeking “beyond this bleak, blind interim of now and nevermore” for “a joy as keen as any plangent woe.” The Atlantis Fragments and The Silmarillion overlap not only because both creators are greatly concerned with the details of textual transmission, but because in both cases the amount of biographical time invested (decades) pays dividends in the illusory form of the historical time (centuries, millennia) conjured up. DSF’s book is much-inscribed with dedications to, and acknowledgements of, people we know or know of like Don Herron, David C. Smith, T. E. D. Klein, Terry McVicker, Ron Hilger, and Lauric Guillaud. Fritz Leiber is represented by “Secretest,” a poem he wrote in honor of DSF while in the air en route from San Francisco to Los Angeles in June of 1969. The second of the three epigraphs for “O Ebon-Colored Rose” is from REH’s “Which Will Scarcely Be Understood,” and CAS, “alchemist of beauty and bale,” is of course a cher maître throughout. Never more so than in the long narrative poem “A Vision of a Castle Deep in Averonne,” in which we revisit Ximes, Vyônnes, and Malnéant, and are updated on old friends like Sylaire, “Saint” Azédarac, and the gargoyle-carver Blaise Reynard. This work turns out to be not so much one last rendezvous in Averoigne as it is a Smith/Shakespeare crossover, adroitly stage-managed by DSF. And given the hysteria of not-so-long-ago, the Francophilia of “A Vision” and other pieces are as much a relief as a Dom Pérignon Rosé Vintage 1959 washing away cold congealed “freedom fry” grease.

As Averonne (“distinct from the rest of France, is it not?”) attests, the poet’s questing takes him beyond even the far-flung frontiers of the Atlantean empire; “Golden Mycenae” is visualized as “This proud lion couchant curled upon his dais,” all tawny majesty unspattered by the gore and filth of the House of Atreus. “Thaïs and Alexander in Persepolis” ends by freezing, and frieze-ing, the arson in thought that preceded the arson in deed: “How, kindled by the Persian flambeau-fires, there flames / A splendor of destruction deep within her eyes.” Tributes to the Empress Eugénie of France and the Empress Zita of Austria provoke dynastic reconsiderations. And TC collectors will recall “To a Dead City” (was Cartagena de las Indias perhaps built on the ruins of an Atlantean outpost?)

By existing DSF guarantees that at least one American associates the name Spenser with the Gloriana-feting poet rather than the Robert B. Parker detective. The “Spenserian stanza-sonnet” is the technical innovation that allows The Atlantis Fragments to proceed, and The Tempest is hailed as “this most Spenserian of Shakespeare’s plays.” Of The Faerie Queen (1590) Mr. Sidney-Fryer says “For the average reader Spenser’s great fairy tale has become the lost Atlantis of our older literature.” Alas, some of us are always going to self-eject from the Bower of Bliss due to sympathizing with the kerns and gallowglasses, and as a result murmur that Spenser’s A View of The Present State Of Ireland, with its famine-engineering and culture-extirpating recommendations, is a lost Acheron of our older literature. Few Sassenachs have asked so loudly, and not particularly poetically, to have their castles torched…

A sort of disciplined whimsy is frequently on display in The Atlantis Fragments, and the tales of “a civilized jungle” with which Sinistra-Theustra and Dexter-Theustra, two heraldic jaguars on permanent duty in the Antillian thronehall, reminisce about their more animate days, are flat out charming. Those big cats notwithstanding, Mr. Sidney-Fryer’s humor is less feline than that of CAS; his playfulness is apparent in disclosures like “The Atlanteans had a predilection for long, rather Whitmanesque , lines” or a Note devoted to the “rather startling resemblance” of “The Song of the High Seas” (by Richard Rodgers and Robert Russell Bennett, for the Victory at Sea series) to “the traditional fanfare of Atlantis, the Archimperium Salute.” No less a figure than Uther Pendragon plays a part in this musical hand-me-down.

The true tragedy is not the foundering of Atlantis but close-minded denial of the island continent’s meta-reality. Sinkings, whether by gods or skeptics, can’t keep pace with surfacings, and nowadays the Atlantean sway as metaphor and simile extends farther than that of Plato’s original thalassocracy ever did — “so much more than merely mythological,” as the “thesis-poem” “Item — Ariel Sings,” puts it. In his aforementioned article on CAS and the Atlantis-theme, Mr. Sidney-Fryer discusses the late Forties as “an enormously fruitful period for Smith, “like some unexpected Atlantis arising, there came into palpable being his last major cycle of new poetry, and of new love poems at that.” Neil Gaiman introduced, or at least identified, the concept of “echo-Atlantises” in his Sandman story “The People Who Remember Atlantis,” and the Hesperian empire was Stephen King’s shorthand in his 1999 collection Hearts in Atlantis for everything that was lost when the Sixties failed to usher in an Age of Aquarius but instead led merely to the Seventies. DSF fashions an epiphanic crystallization of all this in his poem “Remonstration”:

For, all things beautiful but lost, forevermore,

Are Atlantean-like, and intermediary

Between Atlantis and that bright but final shore.

In the Note for “Codacil of Contradiction,” we are told that when this poem was composed Atlantarion “had just finished his final sequence of connected poems, but instead of experiencing a sense of release and elation, he felt only a sense of defeat, as adumbrated in this, one of his final pieces of verse.” We can but hope that the real world poet does not share the feeling of the imaginary world one, but if a sense of defeat has at any point encroached upon what should be release and elation, Aragorn’s words to Boromir at the start of The Two Towers apply: “Few have gained such a victory. Be at peace!”

Almost everyone who deals in or seeks out the literature and art of the fantastic is an exile of Atlantis. Oh, we might be Cataclysm-survivors, but the barbed arrowheads of nostos and algos defy the surgeon’s skill. How to return? No cruise ships stop nearby, nor can we book passage on the Nautilus, or go EVA from a hired bathyscaphe. But in our extremity The Atlantis Fragments arrives like some combination of ticket and visa, means of conveyance and dream-permit, and for that Donald Sidney-Fryer merits an Archimperium Salute; long may he wear the tridented crown.