Dwell for a moment, Dear Reader, on a subject you might never have considered: the practical circumstances surrounding the writing of your own biography, well after the fact of your death and the deaths of all those who knew you best and cared for you most.

The biographer in question would have to conduct interviews with scores of people who knew you little or not at all, and hang on their every word, granting such threadbare testimony an out-sized respect. Think back to your early years in school or in the workplace, to the myriad faces and personalities whom you recall at this late date only in occasional snatches of memory fogged by the passing of decades. How many of their names can you remember? How many conversations? Could you be trusted to give a biographer the rundown on the personality and family of one of your ex-coworkers or fellow students? Could they be trusted to describe your life and family?

If a biographer did some Google searches on the Internet and drudged up everything you’ve written online, and if he managed to score a copy of all of the e-mails you’ve written and saved, would he have an accurate picture of what you felt and thought? Would he be able to chart the often massive changes in your thinking about religion, politics, family, friends, career, art, or anything else you care to name? Could he judge the times you were being purposefully untruthful, or masking your true thoughts in deference to someone’s feelings? Would the vast amount of e-mails you failed to archive have provided a radically different picture of your life?

In my case, I am left thinking, “My God, if someone wrote a biography about me someday, utilizing a selection of emails and the few stories remembered by neighbors and classmates and co-workers and friends and enemies, what an outrageous passel of lies and out-of-context guesses it would be!” Everything I’ve ever written anywhere could be taken as gospel, What Leo Thought, The Truth, The Facts, without regard to changing times and the wisdom and reevaluations of age. People I didn’t even know that well — or worse, people I despised and who despised me back! — would each become a trusted arbiter on my life and reputation. Every independently verifiable “fact” could be combined and extrapolated in a monstrous whole that scarcely resembled reality.

It’s a terrifying and sobering thought.

In Howard scholarship, with our intellect and reason tempered by decades of bitter experiences at the hands of sloppy and malicious forefathers, we have grown more and more careful about taking things at face value. We sift through all the available data and take into account all of the vagaries and caprice inherent in a biographical record, in a way that to the best of our ability “does REH right.” That’s not to say we make things up or paint him in an idyllic light with a halo around his head. It means we try to balance the facts with the intent that hums beneath them, and leaven the concoction with a strong helping of the Time and Place in which they occurred. The strides we’ve made in balancing the Howardian record as a result of these ministrations is plain to see.

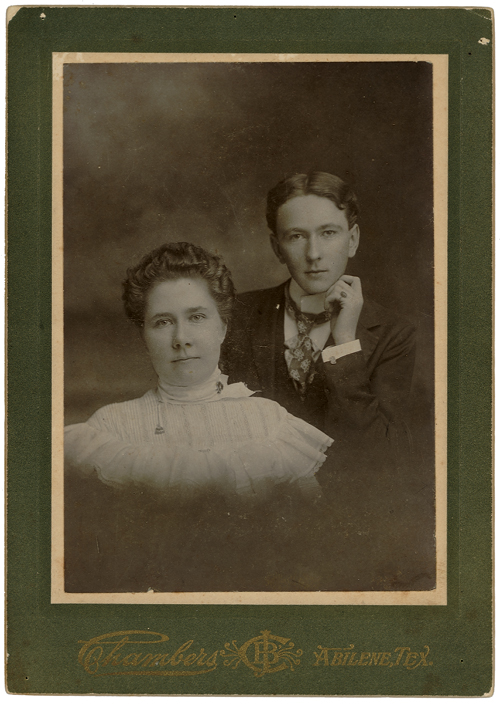

But in the rush to do right by Howard, there has been a conspicuous lack of interest in doing right by his parents. Both Mother and Father loom large in the story of Howard’s life, and yet the two have been routinely demonized as bickering, jealous, damaged, awful parents, who bear a large measure of responsibility for Howard’s depression and suicide. His Mother especially has been snowed under by accusations of quietly demented witchery. For years I’ve grown increasingly sensitive to the methods used to accomplish this. It’s much the same sort of sleight-of-hand that was employed against Howard’s memory for so long, but in Dr. and Mrs. Howard’s case — with much less biographical meat to work with — it is far easier to carry out and far harder to combat. It’s gotten so bad that a few years ago Steve Tompkins opined to me that trying to humanize Hester Howard would at this late date be “fiendishly difficult,” like trying to rehabilitate “Grendel’s mother.” Given the amount of garbage that has made it into print, it’s hard to argue with such pessimism. “Has there ever been a pro-Hester faction, aside from REH himself?” Steve asked me at the time.

The answer to that question, it may surprise you to learn, is yes. I’m pro-Hester, and after ten years of study have come to believe that the rap on her is every bit as luridly overblown as the worst myths about REH. Various stories and opinions have their place, sure — but what proof do we really have that Howard’s mother was the monster she is portrayed as? Annie Newton and other catty neighbors and relatives with apparent grudges didn’t have much good to say about any of the Howards in interviews prepared by L. Sprague de Camp for Dark Valley Destiny, although to get a better read on the true context of those interviews they will have to be released in full someday. In One Who Walked Alone Novalyne Price Ellis appears to have faithfully recorded events, yet too often she can be seen to interpret them with frightening naiveté, as when she flippantly told REH to solve his problems by shaving his mustache when he was teetering on the brink of despond, and when she wondered why Mrs. Howard couldn’t just jump up and be as self sufficient as her own Mammy (earth to Miss Price: your Mammy wasn’t dying). E. Hoffmann Price’s outrageous ego and penchant for BS is hard to trust, especially when his retellings of the same stories got progressively weirder and more anti-REH over the years, as the dead Texan’s reputation began to far exceed his own.

Set against that thin gruel you have some stubborn facts. Hester spent many of her first thirty-four years selflessly taking care of sick relatives, in the process forgoing the happiness of marriage and contracting the illness that would kill her thirty years later. (gee…I wonder where REH got his notions about caring for ill family members from?) According to her step-sisters and relatives she was beloved by that entire side of the family, known and revered for her many kindnesses. Her funeral attracted mourners from several states. Others report that she had many friends all across Texas and when healthy would visit them as often as she could. Until her health failed she helped her husband with his medical practice, running various machines and other apparatus. She enjoyed attending church and picnics and festivals in town, and was remembered by Price and other guests and friends as a gracious host.

Mrs. Howard infused in her son a passion for poetry, ancestry, and the history of the Southwest. She always believed in him, prodded him forward, wrote letters to the magazines he wrote for, yelled at the neighbors when they complained about his typewriter clacking away at all hours of the night, and protected his writing time from intrusions. Through most of his adult life REH went wherever he wanted and did whatever he wanted with no mind-control or withering disapproval that friends remember. The only evidence we have of REH staying close to home is in Ellis’ book, in the last two years when Hester Howard’s health had become critical. Common sense and imagination hint at a hidden reality too nasty for Novalyne’s youthful self-centeredness to allow for: night sweats, puke and sputum, gross incontinence, IVs and drainage tubes, moaning, crying, delirium. Yet even during those years Bob went to New Mexico with Truett Vinson and made other trips as opportunities warranted. At the time Ellis was fairly consumed by her romantic fits of pique, but in the real world REH was acting more mature and had his priorities straight. And Ellis and others thought Mrs. Howard was faking to get her son’s attention, but she’d have to be pretty dedicated at this ruse in order to create gallons of fluid in her abdomen that needed to be drained, and then later to up and die. In the final analysis, her detractors were wrong: she hadn’t been faking the severity of her illness, she had been dying a miserable and painful death all along.

Some of the gossipy stories about the Howard marriage may have a factual basis, but accurate context is key. Annie Newton’s incessantly catty anecdotes are offset by those of Bob and Marie Baker and Norris Chambers, all of whom I personally interviewed and pressed and pressed on these points, and who each gave essentially the same story: Dr. Howard was loud and boisterous (in an entertaining rather than boorish way, people loved his personality) and frequently said things in mock anger as a joke, but it was abundantly clear that he loved his wife and son dearly. For instance, de Camp and one of his interviewees believed that Isaac calling Hester “Heck” was an insult, but the people I interviewed maintained strongly that it was a term of endearment. None of the people I have interviewed recall a single instance of him truly insulting his wife in their presence; all stressed his deep love and respect for her.

These stories fit in neatly with those stubborn facts: REH’s father provided heroic care to his wife in her final years, carting her all across the state for various treatments, hiring at-home nurses, and calling in favors from doctors throughout the area. When his wife and son died he was devastated, couldn’t stay at the house for months, burst into tears regularly for weeks, and for years afterwards agonized over their graves and whether they should be moved to a nicer cemetery, going so far as to drag Norris Chambers on numerous exploratory excursions to graveyards in different parts of the state. What many Howard fans call Dr. Howard’s greed and opportunism in the aftermath of their deaths I call due vigilance from a grieving father who had heard his son rail at cheap thieving editors for years, and who didn’t like playing the fool for anyone. If he was too paranoid and angry in those early months, so be it — he was an old, beaten, devastated man doing his best by his son’s memory in a field he had no experience in. A certain amount of defensiveness and frustration was to be expected, and in my opinion any attempt to call him greedy based on a few dunning letters and court records would show a profound lack of imagination and empathy.

One of the de Camp stories that bothers me most is where Hester Howard laments that her husband’s mother “just won’t die!” as if she wanted her mother-in-law to expire. We’ll never know if she said such a thing out of pity, genuinely wanting the woman to finally be relieved of her pain, or if she said it as an ill-considered joke that was meant to be lighthearted but clanged off the rim, or indeed if she even said it at all. It’s quite hard for me to imagine someone treating others so kindly for so many years, only to turn into a snake once married. I’ve heard my mother and father make such jokes lightheartedly in front of my nonagenarian grandmothers for years, and I wonder if other, more tight-laced people listening in would be quietly appalled, even as my grandmothers laughed up a storm.

Steve once mentioned to me that it is worth considering why there is an almost complete lack of Mother-figures in Howard’s work. Is that big black hole where the hero’s mother should be indicative of some parental neurosis? Perhaps…but examples of stories lacking any mention of the hero’s mother are legion, and — thinking specifically of the pulp jungle — the last thing readers wanted was some old lady taking screen time away from the hero and damsel in distress. Those Brundage covers would start getting pretty scary. Besides, REH never seemed comfortable writing about anyone not focused through his prism of hate and feud. Woman and children frequently got short shrift throughout his work except when they could be leveraged as appealing victims or vengeance-deliverers. Howard’s work is thematically focused more than most authors, often to the exclusion of all else, and hence often lacks much of the peaceful, mundane, familial aspects of life. Mothers are just one example of that. Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

Rather than being tricked or forced into an unholy love for his mother, REH looked on his mom as a hero based on the facts on the ground: tales about her hard frontier youth, her many sacrifices to help her family, her unflagging support of his hopes and dreams, and the stoic grace she displayed while suffering and dying while the town around them jeered that she was faking it for attention. I can well understand how both mother and son grew bitter and introverted in the face of the condescension that Cross Plains residents had for expatriates from Burkett and Cross Cut (something Marie Baker in particular hammered home to me), just as Brownwood in turn looked down on the people from Cross Plains. Howard knew his mother had always wanted a better, more urbane life, and as old age and sickness dragged her inexorably away from that possibility and towards death, his rage at the unfairness of black fate grew exponentially, eventually eating away at him until all that was left was bleak resignation. None of this demands that Howard be a slave to his mother or her whims, or that she be a Machiavellian terror.

Had REH really been in a love-hate relationship with his mother, wouldn’t true confidants such as Tevis Clyde Smith or Novalyne Price have heard plenty about it in some shape or form? All we have is REH patiently explaining his true situation to Novalyne again and again: how his mother was a damn good woman in his eyes for all the reasons explicated above, how her sickness forced him into massive responsibilities that harried him but which he nevertheless felt obligated to fulfill, and how his Dad was doing the best he could as well. His frustration that Novalyne can’t get her head around his true relationship with his mother, and indeed Mrs. Howard’s true nature, is palpable.

I can reasonably accept that, like her son, Mrs. Howard could be cold or standoffish, especially as she got sicker, and that she wanted to live in a different town and have nice things and mannered friends. I’ll agree that when faced with a young, headstrong, demanding girl pouncing on her son after years of the status quo, she very well might have treated Price with icy distrust and feared for her son’s writing career and happiness, not to mention her own needs. I can grant that like all families they had yelling matches and fights, albeit ones that probably sounded to outsiders a lot worse than they were. But all of this is well within the range of the average family, especially when Hester’s sickness and REH’s odd career are factored in.

But listen to how L. Sprague de Camp routinely took positive stories about the Howards and twisted them into the nightmare portrait he was trying to create. Throughout the book he railed at “the small deceptions that they practiced to satisfy their need to be thought well of…small fictions maintained by the family, which, taken together, gave young Robert a distorted view of reality…an unsettling conceptual chaos…a sense of chaos tantamount to world destruction…isolated and so deprived of the normalizing functions of social interaction…overprotection of his parents…few experiences with the real world…Hester Jane’s sense of inadequacy…her feelings of rejection and dependence…personal unhappiness and conflict…people who lack adequate techniques for coping with their environment…a kind of infantile despair, which resulted in a flight from adult responsibilities…” This only covers a few pages of a biography awash in such judgments.

The problem de Camp had was all of the people that loved and admired Hester. Any testimony about a vibrant, laughing, normal woman needed to be neutralized. Thus we have passages such as the following (de Camp’s sleight-of-hand in bold): “Ambivalent though she must have felt about her father’s new wife, Hester Jane was too dependent to be openly hostile. She got on well with her stepmother and readily took on the role of assistant mother.” Note the shell game at play here: de Camp has just turned the factual reality of getting along well with her stepmother into proof that she was secretly hostile to that same stepmother. The truth is that she “got on well with her stepmother” — that is what de Camp was told by his interviewees. But that wouldn’t give him an easy explanation for Howard’s suicide, so that truth has to be covered in rhetorical manure and the jungle moss of psychological speculation.

Here’s another gem from Dark Valley Destiny: “During her pregnancy, Hessie was all smiles and laughter, forever joking with her neighbors, but she never left her husband’s side. She traveled with Dr. Howard wherever he went. Her fear, and the dependency it generated, must have been enormous and unquestionably carried over into her relationship with her son.”

So again, the facts on the ground — given to de Camp by the testimony of his interviewees — was that Hester “was all smiles and laughter, forever joking with her neighbors.” That she traveled with her husband “wherever he went” may be factual, too, but any speculation as to why she did so is just that. Given her “smiles and laughter,” could not the reason be something other than “fear” and “dependency”? Just maybe? Hmmmmm?

De Camp was an expert at taking gossamer personal opinion and spinning it out into a base for portraying REH and his family as a seething cauldron of resentment. Try this one on for size: “Long and frequent dislocations, such as Hester Jane had experienced, do not make for happy wives or relaxed mothers. Thus, it must have been a strained and uncertain if beautiful bride whom Dr. I. M. Howard took to wife.” The “long and frequent dislocations” de Camp is talking about are the occasional travels Hester made between various members of her family, often with the purpose of caring for sick relatives. Elsewhere in the book, de Camp admits about that same family, “As each little half-sister arrived, Hester Jane became her loving companion and was always remembered with warmth and gratitude. They all came to Hester Jane’s funeral, bringing with them their abundant loyalty and honest grief. They were charming people, these Ervins, and their graciousness and courtesy were part of Robert Howard’s heritage, too.” And yet given all of that, he nevertheless feels justified in assuming that Hester Howard going to live with these “loving” relatives, who recalled her with “warmth and gratitude,” must have left Hester feeling “strained and uncertain”! De Camp does this so oily and glibly because without making these audacious leaps of cause-and-effect, boldly integrating them seamlessly into the record, the conclusions he draws about Hester’s malignant hold on her son would turn to dust. Multiply these invented scandals by a few hundred times, and you can begin to see how the old science fiction grandmaster’s Dark Valley Destiny research — and especially his relentlessly jejune, quasi-psychological interpretations of it all — have over time achieved a subliminally canonical presence in the field.

(As an aside, flipping through the various biographies, what’s with the overwhelming preference for referring to REH as “Robert,” or the even more infuriating “young Robert,” like a scolding parent admonishing a pouting child? The man’s name was H-O-W-A-R-D, Bob to his friends, and the respectful thing to do — as a quick reading of most any biography or newspaper article will attest — is to refer to him by his last name as a general matter of course, with less-formal designations being brought in as the need for variety dictates. I can’t help but recall Howard’s plaint to his friends, “Why do youse bastards keep calling me Robert?” spoken after they had apparently been teasing him for a spell by repeatedly and deliberately using his formal first name.)

Most galling to me is the now-ubiquitous idea that REH was a suicide because his parents raised him as a misfit from the Island of Lost Toys, that their awfulness damaged him in his youth and set him on the highway to hell. REH deserves the courtesy of being confronted as an educated, mature, free-willed adult, one who made his own decisions and fought his own demons as a man. And his parents don’t deserve to be saddled with a reputation as suicidally unpleasant ogres because their adult son killed himself. He died at thirty, not thirteen.

My conviction is that REH was an adult, a man. He went as he pleased, did what he wanted, is even on record as cussing out his Dad in front of his friend when he needed the car. He had been insinuating suicide for years without ever actually trying it, arguing with friends that it was a valid way to check out and writing eerie, almost loving poems about it. After ten years of dealing with Bob the Loner, Bob the Gloomy Grump, how many people in his social circle were convinced he was faking his level of despair, the same way people had erroneously assumed his mother was faking the illness that killed her? Today, we’ve been inundated with studies and news items urging us to take all such warning signs deadly serious and call a hotline…but then?

Add to that REH’s craftiness (all too common in determined suicides), tricking his Dad by first putting him at ease and then suddenly doing the deed before his mother had died. Might Howard have similarly reassured his Mother while she was conscious, promising he wouldn’t act rashly, all the while fully set on going through with it once she was so far gone that she “would never recognize him again”? And if he did trick her in this way, could she be faulted for thinking her attempts to dissuade him from suicide had succeeded? And what exactly does this say about him being tied to her apron strings? Go to some suicide websites. Read the stories. Howard’s death isn’t some weirdo thing, it’s all too common in all of its tragic “woulda-coulda-shoulda” particulars. Suicides leave behind dazed loved ones who only in hindsight are able to piece together all the clues, leaving them consumed with guilt at their inability to prevent the act.

I also am increasingly convinced that the stories of his parents shielding REH from Life — the death of his dog Patch, et cetera — have been grossly exaggerated and misconstrued. From a fairly early age REH was depressed, often spoke of killing himself, and argued passionately for the philosophical right to do so. Far from causing his behavior by always keeping their son safe and isolated from reality, could they not have been presented with this inexplicable, frightening logic, and then began trying their level best to dissuade him from his stated goal, to the degree that they even believed he was serious? Happens all the time — good kids and adults, raised well and living in good homes, becoming horribly depressed and then killing themselves without apparent reason, leaving the parents helpless, confused, worried, and ultimately devastated and asking “Why?”

All of this makes far more sense than the theorizing about how his parents weirdly and craftily molded him into a pampered recluse unable to deal with the world. Depression of all kinds and causes can pave the way to suicide when it becomes so great and ubiquitous that the fear of dying becomes less of a horror than the pain of living in mental agony. Far from being the catalyst for opening the door and pushing him towards it, if anything the love and support from his family seems to have been one of the only things that kept him from pulling the trigger much earlier, that helped to hold the demons at bay. It was when that love and support threatened to crumble and vanish, with nothing — no “great love or great cause” — to take its place, that he decided “the game wasn’t worth the candle.” No hard proof one way or the other (there rarely is with suicides) but when you read the stories of other people doing the same thing, it all fits Howard like a glove. His suicide strikes me as typical, amazingly so, almost pedestrian. Artistic vocations attract depressed people unsatisfied with the Real World, and such people disproportionately commit suicide. At some point, it becomes silly to blame people’s parents for the actions of their adult lives.

Look over Wikipedia’s List of Famous Suicides. That’s a lot of wicked mothers working overtime! My conviction is that ultimately people are responsible for their own destructive impulses, whether they are thirty-somethings like Howard, Michael Hutchence, or Peter Ham from Badfinger, or sixty-somethings like Hemingway or George Sanders or Hunter Thompson. Depression is by far the deadliest killer on that list, not mothers. If Mrs. Howard had been hitting REH with hangers his whole childhood, that might be a different story. But coddling Howard into the grave? By using such criminally abusive tactics as making him wear clean white shirts to school, forbidding him from playing football, exposing him to things like poetry, and not passing along phone messages? Oh the horror!

I’ve said before that conscientious biographers can’t rely solely on first- or secondhand stories and papers dug up and arranged like so many butterflies coated in formaldehyde and pinned into scrapbooks. The corpses might be colorful and even anatomically correct, but so much of the life and beauty of the creature is lost, and can only be gained by seeing one alive and in flight. Where a biography is concerned, especially when the person in question has left scant evidence of the fullness of their personality, you have to also look at the Big Picture and use copious amounts of imagination and common sense. A more sympathetic and understanding analysis of the Howard family shows three people who cared deeply about one another and stayed together until the end despite being wracked by tragedies that I wouldn’t wish on anybody. There is a place for the negative stories, yes — but they deserve to be accompanied by the other side of the coin, the laudable familial bonds that held the Howards together throughout their lives. These things should be relayed not in the minimalist, grudging, giving-the-devil-her-due fashion de Camp and his ideological soulmates employ, but with a full-throated and generous magnanimity.

Hester Howard was a woman of uncommon strength and dedication to family, one remembered by many as a laughing and loving woman, a good friend and genial host, courageous in the face of illness and death, a lover of poetry and fine things, a lady in the truest and most noble sense of the word. Some families even named their daughters after her, such was the depth of the admiration of her friends. She is not responsible for the adult despondency and suicide of her son — it’s clear that Robert E. Howard adored his mother, and her fatal illness filled him not with resentment but with an unutterable sadness about the horrors of old age inflicted by a heartless, cruel world. She deserves to be remembered far more charitably than she has been. Until such time as she is, this little blog post and my occasional prayers to her memory will have to do.