Grim Lands: First Impressions

Thursday, December 6, 2007

posted by Leo Grin

We’re barreling towards Christmas and, as always in early December, posting has become awfully light around these parts. Finn is running his movie theater, [redacted] is traveling for a school soccer tournament, and Steve is hiding behind the ten-foot-tall stack of books in his to-be-read pile, plotting new sorceries to unleash on his coterie of blog admirers. That leaves lonely old me to take a break from working on three different print issues of TC long enough to check in here and mouth off about the latest Howard book to hit the mean streets.

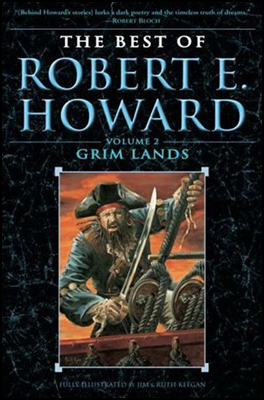

THE BEST OF ROBERT E. HOWARD VOLUME 2: GRIM LANDS

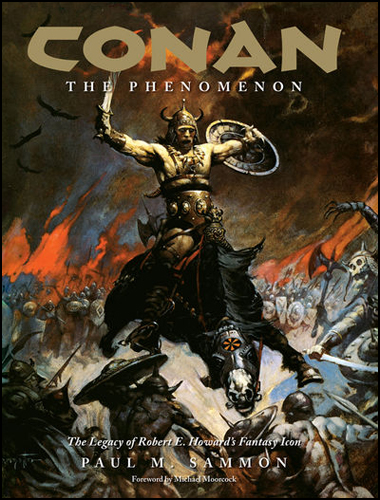

This book appeared in late November, giving Howard fans the first complete Best Of set worthy of the name since Skull-Face and Others in 1946. In a sense, these two volumes are designed more for the reader who is not yet a fan — as Rusty has often stated, the intention was to be able to hand these books over to the unconverted and say, “Here — if nothing in these pages captures your imagination, then REH ain’t for you.” With Conan, Kull, Kane, Costigan, Elkins, and a host of minor celebrities all vying for the reader’s attention, I’m guessing that few people will walk away without something tickling their fancy. Whether your mind drifts towards low comedy or high drama, dark history or the bright glare of a boxing ring, blades of Damascus steel or the smooth gleaming barrel of a Winchester, there’s many things within these pages for you. I haven’t yet, but I intend at some point to read these cover to cover, savoring the interplay and the thrill of having Robert E. Howard’s finest tales and poems presented one after the other, without the usual low-grade filler bringing the reader down from the rhetorical highs of his best stuff.

The art matches the high standards set by Crimson Shadows, and indeed by the “Adventurers of Two-Gun Bob” comic strips the Keegans have been producing for Dark Horse’s Conan title. After flipping through this latest book, I stand by my previous proclamations that the Keegans have done the most well-researched, most daringly original, and, in a word, the best work out of all the Wandering Star/Del Rey artists. Not to take anything away from the others, but clearly there is a fire burning here that had been smoldering for years, a desire to do right by Robert E. Howard that was not going to be denied. Filtered through the prism of Ludwig Hohwein and spiced with thoughtful, often tenderhearted nods to everyone from Pyle and Wyeth to Ditko and Schulz, Jim and Ruth make full use of the massive literary sandbox they have been given to revel in. I don’t profess to have any real skill at judging art or spotting influences with any accuracy, but even I can notice that there’s an insistent stream of quiet, almost subliminal homages popping up here, referencing everything from old newspaper comics to the distinctive pulp cover art of the 1930s to memorable compositions of favored film directors. Even the most minor touches delight, such as the drawing on page 286 that manages to capture the indefinable gloss of an old image from the dawn of photography, showing us that touching familial warmth that often peeked out through the stiff poses and solemn demeanor of people caught in the firing-squad glare of then-futuristic Daguerreotype cameras.

Unlike previous volumes, there are no drafts or miscellanea here, just an introduction by Rusty Burke and a much longer afterword by TC‘s own Steve Tompkins. In the years since Wandering Star’s first release in 1997, Rusty has developed a certain confidence of purpose with these introductions, a surety and clarity that serves both the book and Howard fandom well. The somewhat tentative, still-gelling musings of old have solidified into a measured case for Howard’s talent and worth that strikes a dulcet tone of strength, without resorting to either the hyperbolic screeches of fandom or the increasingly de rigeur cluelessness of most pro writers who write about REH. For those of us in whose minds Howard looms large, it’s sometimes difficult to resist overloading pieces for a general audience with excess baggage of a sort appealing only to die-hard Howardists. Like in his recent National Review interview, Rusty has become increasingly adept at riding this line, giving newbies the information they need while providing hints of avenues of further discovery to those so inclined. I’m more anxious than ever to see Rusty knuckle down and complete a Howard biography, because it’s more apparent each day that he’s reached a place in his mental wanderings where he could really do the subject justice.

Steve’s essay at the back of the book is the Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy from Brooklyn at his most unfettered, the literary equivalent of The X-Men‘s Magneto raising his gauntleted hands to the heavens and summoning an entire city full of metal to his beck and call in one apocalyptic expression of power. As mere mortals, the rest of us can do little but stand aghast at the sight and collect our SAG extra wages at the end of the day. I was so overwhelmed by this cosmic Twister game of lit-crit references — twenty-seven pages worth — that I felt strangely compelled to count them up:

Frederick Jackson Turner, Tom Pilkington, Edgar Allan Poe, John Clute, Verlyn Flieger, J.R.R. Tolkien, Brian Attebery, J.K. Rowling, Thomas Jefferson, L. Frank Baum, Walt Disney, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Gordon R. Dickson, C. S. Lewis, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, D. H. Lawrence, Herman Melville, Philip K. Dick, Charles Lindbergh, Ian Fleming, John Wayne, Garry Willis, Amerigo Vespucci, George Templeton Strong, Charles Sumner, Preston Brooks, Walt Whitman, Henry James, John Dos Passos, Henry Miller, T. R. Fehrenbach, Paul Horgan, Richard Matheson, Charlton Heston, Anthony Zerbe, Tom Shippey, Henry David Thoreau, Herodotus, Cyrus the Great, Aubrey de Sélincourt, A. R. Burns, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, John Huston, Humphrey Bogart, Howard Hawks, Quentin Tarantino, Michael Chabon, Stephen King, Harold Bloom, Paul Seydor, Sam Peckinpah, Leslie Fiedler, Ann Douglas, James Fenimore Cooper, William Carlos Williams, Richard Slotkin, Eugene O’Neill, Stephen Crane, Jack London, George Orwell, Alfred Kazin, Christopher Marlowe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rafael Sabatini, Billy the Kid, Shirley Jackson, Mary Hemingway, Archibald MacLeish, Richard Chase, George Steiner, Larry McMurtry, Katherine Ann Porter, Virgil, Cotton Mather, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Tony Tanner, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Carl Van Doren, James Branch Cabell, Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, Joe Louis, Max Schmeling, Bernard DeVoto, W. H. Auden, Richard Poirier, and The Brothers Grimm.

Many of the above-listed names are not only mentioned but quoted, some multiple times, with the excess overflowing out of the essay proper and into footnotes. And all of this doesn’t include the Howardian references, dragging in everyone from Novalyne Price Ellis and her cousin Enid to David Weber, Tevis Clyde Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, Arnold Schwarzenegger, John Milius, Patrice Louinet, Rusty Burke, Clark Ashton Smith, Steve Trout, E. Hoffmann Price, and Farnsworth Wright. It’s ten essays for the price of one, and those of you who like to trip the light fantastic with my fellow blogger no matter how crowded the dance floor becomes will definitely get your money’s worth. I managed only a half-dozen pages before skimming the rest, then pushing my plate away with a belch and politely refusing the dessert menu. To each his own: some readers have an insatiable need for speed, and the rest of us get sick when the roller-coaster is amped up with that many G’s. In my case, this essay was akin to the centrifugal chamber in the James Bond film Moonraker, spinning me around and spitting me out with a (it is to be hoped not permanent) case of Howardian motion sickness. Perhaps I’m wrong — I’ve often come back to things after a spell to discover that I can engage with them much better the second time round. But any future attempts will have to wait — I’m still reeling with dizziness from the first ride.

In other news, Paul Herman has announced that Howard Works, his Cimmerian Award-winning bibliographic website, is being taken under the umbrella of The Robert E. Howard Foundation. I haven’t the slightest idea what this means, but it should be fun to wait and find out. Eventually, many of the Foundation’s nascent initiatives are going to begin to grow and pay off for fans and scholars, it’s just going to take time for it all to mature. I always thought that Howard Works is well positioned to expand its reach beyond bibliographic information, and also include things like story summaries, character listings, indexes, and the like. We’ll see what happens.