An Irish Bard at King Hrothgar’s Court

Sunday, November 11, 2007

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Nothing in Robert Zemeckis’ Marty McFly-and-Roger Rabbit-ridden career kindles much optimism on the part of the heroic fantasy enthusiast that the November 16 release Beowulf will be aught but a Polar Express to embarrassment. In as startling a makeover as has occurred since Stanley Kubrick chose to present Stephen King’s woman in Room 217 to Jack Torrance as an incarnate wet dream (at first), the TV promos have been playing up Grendel’s mother-the-MILF in the seal-sleek form of Angelina Jolie.

We can but warm ourselves at a few embers of hope provided by the innovative work of screenwriter Neil Gaiman with Northern motifs in The Sandman and American Gods, or the casting of Ray Winstone, such a powerful presence in Sexy Beast and the irrigating-the-Outback-with-blood Australo-Western The Proposition. Beowulf himself is technically pre-English, a Geat, but is there a more Saxon-looking actor than Winstone? He’s like some Norman nightmare of burly axe-wielding obduracy glaring at the invaders from the shield-wall at Senlac.

Also encouraging is the welcome surprise of a just-appeared 353-page novelization of the film by Caitlín R. Kiernan. Irish by birth, Alabaman by relocation, a specialist in vertebrate paleontology by training (she knows her way around a mosasaur), and a sable-dark fantasist by inclination, Kiernan is a writer in whose slipstream I’ve been mouse-clicking frantically since S. T. Joshi accorded her story “In the Water Works (Birmingham, Alabama 1888)” the honor of closing out American Supernatural Tales. Novelizations are of course tie-ins, a polluted-because-ancillary revenue stream, but Kiernan (whose Threshold, a 2001 “novel of Deep Time,” uses Beowulf as an underlier-text) manages to transcend that stigmatized and intrinsically subliterary category to produce a powerful contribution to the “Northern thing.” Her Beowulf is no mere novelization but a novel, one whose tragic heft and mythic lift would not disgrace a shelf-berth next to Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword, Hrolf Kraki’s Saga, and The War of The Gods.

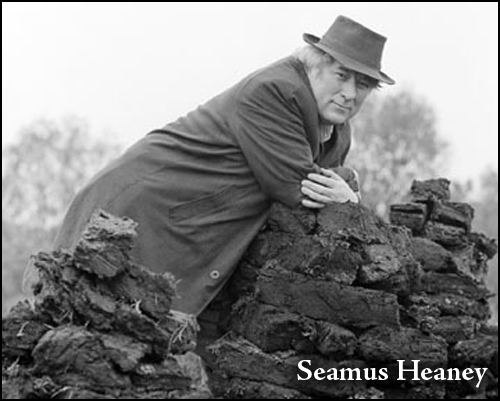

In her Author’s Note Kiernan sternly addresses students who might be eager for a shortcut: “If a teacher or professor has assigned you Beowulf, this novelization doesn’t count. Not even close,” and another point in the Zemeckis/Gaiman project’s favor, sight unseen, might be the motivation it affords to return with all deliberate speed to Seamus Heaney’s 2000 Beowulf: A New Verse Translation.

Heaney scored one of the least debatable recent Lit-Nobels for poetry collections the titles of which (Door into the Dark, Wintering Out, North, and Opened Ground: Selected Poems 1966-1996) hint at his qualifications for braving the Beowulfian barrow, and he acquitted himself superbly with a different part of the Western inheritance in his play The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles’ Philoctetes. One reviewer of Beowulf: A New Verse Translation said in 2000 that Heaney had made a masterpiece out of a masterpiece; and the hoary poem could not have been rendered more accessible had the new version come with a free microchip implant to bestow fluency in Old English on readers. In an early draft of “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” the immortal 1936 lecture that liberated Beowulf from the palsied grasp of those who deemed it overly monsteriffic and therefore deplorable or disposable, J.R.R. Tolkien invoked the poem’s “murmurs of the primeval Teutonic forest” and “sounding of the Scandinavian sea” while emphasizing that “they are memories already in [the poet’s] day of a far past caught and coloured in the shells and amber of tradition, and refashioned by the jeweler of a later day-the great day of the Anglo-Saxon spring.” Heaney, the jeweler of an even later day (the autumn of the Anglosphere?) has refashioned and revealed more facets than ever before.

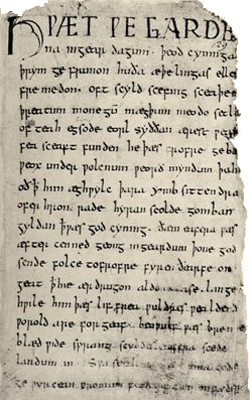

Beowulf is at one and the same time the oldest survival and a comparatively recent arrival in English literature, depicting an age undreamed of by Chaucer, Malory, Shakespeare, Milton, and Keats. They never had the chance to read the poem, which indeed earned its Seamus Heaney the hard way, barely eluding a more implacable Dragon than that met by its hero inside the poem-Time, whose old serpent-jaws gape wide enough to swallow any prey and gnaw like Robert E. Howard’s “lizards of desolation.” No better short account of this feat exists than that included by Tolkien scholar John D. Rateliff in his essay “‘And All the Days of Her Life Are Forgotten’: The Lord of the Rings as Mythic Prehistory”:

We have hundreds of surviving manuscripts from antiquity of Homer, and what are considered to be the complete works of Plato, and many manuscripts of Vergil’s Aeneid. Contrast this with Beowulf, universally acknowledged the finest work of Old English poetry, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, matched in Middle English literature only by Chaucer at his best, if at all. In each case the poem survives in a single copy, one manuscript. Both these solitary manuscripts in turn by luck survived the disastrous 1731 fire at Ashburnham House that destroyed or damaged roughly a quarter of the Cotton Collection to which they belonged; even the Beowulf manuscript itself was scorched along the edges and had already begun to crumble away before the first transcription was made from it, decades after the fire.

That initial transcription at the ominously named Asbburnham was done by G.T. Thorkelin, possibly a descendant of Hrothgar’s Spear-Danes, who came away from his 1786 visit to England with two copies that preserved letters, words, and whole lines that were otherwise crumbling away in the fire-damaged Cotton Collection manuscript. As Beowulf-translator David Wright tells it, “But when the English bombarded Copenhagen in 1807…Thorkelin’s house was burnt and his edition destroyed. Fortunately, both transcriptions of the poem were saved.” (During certain wearing-of-the-green moods it occurs to me that it might have been “poetic” justice had the Royal Navy destroyed the only complete copies of the Sassenach national epic, but thoughts of the dozens of tragedies by Aeschylus and Sophocles that I’ll never get to read thanks to the incineration of the Library of Alexandria soon shame me out of such spitefulness.)

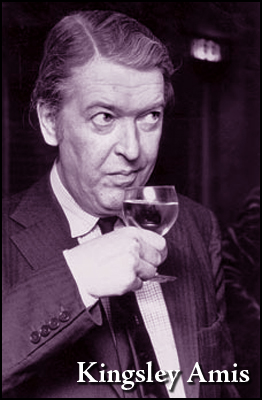

Not that there haven’t been those who would have cheered on the English gun-crews — take Kingsley Amis, who raged against “the anonymous, crass, purblind, infantile, featureless HEAP OF GANGRENED ELEPHANT’S SPUTUM, ‘Barewolf,'” in a March 18, 1946 letter to his friend Philip Larkin. He renewed the attack in 1947, objecting to “The warriors and broken-down retainers who strut bawling across its pages repel by their childish fits of self-glorification and self-pity,” as well as “moral maxims of indescribable triteness.” For anyone unfamiliar with Amis and Larkin, the former was for my money the most gifted English comic novelist of the 20th century, while the latter was arguably the best post-Auden English poet, and yet Beowulf and the privilege of attending Tolkien’s lectures on the poem at Oxford were wasted on them. Just as none are so blind as they who will not see, none are so tenuously literate as they who will not read.

Nor should we forget those who misread, or those who read only in furtherance of a dreary agenda. As Tom Shippey points out in an invaluable 1978 overview, the poem “is almost indecently paraphrasable as ‘three fights with three monsters,’ and yet no matter how much you compress it, it still looks broken-backed; there is no relationship between the second and third fight at all…” Without giving too much away, screenwriters Neil Gaiman and Roger Avary have taken fairly drastic measures to link the second and third fights. Whether or not they were inspired by a Tolkien reference to “the dark background of the court of Heorot that loomed so large in glory and doom in ancient northern imagination as the court of Arthur,” they’ve found for their apocalyptic denouement a truly terrible Mordred.

“The poem is defenceless,” Heaney stresses early in his introduction, “We do not know when it was written, or how, by whom, or for what kind of audience. It is, accordingly, easy to fit ‘backgrounds’ to it and insist that these must dominate interpretation.” Tolkien, who with some justification liked to imagine that a James Allison-like intimacy existed between himself and the poet, in his lectures sought to dispel the latter’s anonymity by awarding him the name Heorrenda. But despite the professor’s prodigies of pedant-slaying and belittler-banishing in 1936, the background-fitting industry continues to belch overdetermined interpretations into what should be a pristine northern sky. In his 1996 The English Warrior: From Earliest Times Until 1066, Stephen Pollington could be channeling JRRT in the following outburst:

It is remarkable that the principal aim of most scholarly work on the poem over the last twenty years has been devoted to showing that virtually every aspect of the poem must have its source in biblical, especially Patristic, literature, even though all these aspects of Beowulf’s character as presented in the poem are perfectly consistent with the picture of a (somewhat idealised) Germanic hero; in other words, it seems to me that scholars have decided that a theme as noble and fine as this poem undoubtedly conveys cannot have been the product of the benighted English imagination — it must have been brought in, borrowed from some older, wiser culture.

Heaney acknowledges “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” early in his introduction, and his comment that the poem’s dragon “has a wonderful inevitability about him and a unique glamour” echoes Tolkien’s famous insistence that “Nowhere does a dragon come in so precisely where he should.” If we sense that a torch has been passed, it has been passed to a worthy recipient, because the aforementioned introduction is a planetarium laser show of intellect and imagery. One of Heaney’s observations, that “gold pervades the ethos of the poem the way sex pervades consumer culture,” is as perspective-enhancing as having a thane-bench broken over one’s head. And here he is on our favorite shadow-stalker: “Grendel comes alive in the reader’s imagination as a kind of dog-breath in the dark, a fear of collision with some hard-boned and immensely strong android frame, a mixture of Caliban and hoplite.” Better yet, he knows that dragons require rescuing not from extinction but from domestication and Disneyfication:

Once he is wakened, there is something glorious in the way he manifests himself, a Fourth of July effulgence fireworking its path across the night sky; and yet, because of the centuries he has spent dormant in the tumulus, there is a foundedness as well as a lambency about him. He is at once a stratum of the earth and a streamer in the air; no painted dragon but a figure of real oneiric power…

That he is, now more than ever, thanks to Heaney.

Could even Kingsley Amis, who died in 1995, have maintained his hostility in the face of Heaney’s version of the poem? We never smirk at this Beowulf & Company as prehistoric lager louts, or laugh at Heorrenda’s work because of a translator’s klutziness as has been the case with some well-intentioned previous editions; instead, here and there we laugh, or smile, with the poet, at the the downplaying of enormities, the whistling past graveyards even if the graveyards are located in Helheim, which is the most attractive aspect of the old Northern temperament. Of Beowulf’s death-grip on Grendel Heorrenda-and-Heaney tell us “He did not consider that life of much account to anyone anywhere,” and when the time comes for us to visit the firedrake’s barrow: “No easy bargain would be made in that place by any man.”

Words, like other structures, are often haunted — can anyone steeped in weird fiction or classic American literature encounter the indispensable Beowulf-ian noun “tarn” and not think of “The Fall of the House of Usher?” The words of the original text are printed on the left-hand pages of Beowulf: A New Verse Translation and function as the bass line to Heaney’s lead guitar. Some few are so recognizable as to penetrate the iron Norman curtain that separates us from Old English: “wyrm hat gemealt/the hot dragon melted,” for example. With “eald sweord eotenisc” the word eoten is cousin to the Norse jotun and lives on in the Ettenmoors of Middle-earth, and so we have an ancient weapon from the age of the giants.

Heaney for his part studs his lines with unusual words, dialect-words, coelecanth-words of a vivid particularity: “Wassail” is easy enough, but we’re also tested by “bothies,” “war-graive,” “mizzle,” and “bawn” (more on bawn a bit later). On the morning after one of his monster-tussles Beowulf is “hasped and hooped and hirpling with pain, limping and looped in it.” That’s just plain fun to read, and even more to recite.

When the Geats make their landfall on the Danish coast, there sounds “a clash of mail and a thresh of gear.” “Clash” is standard-issue, but “thresh” is perfect. Heaney’s coinages and compounds could not be tastier: “wound-slurry,” “blood-sullen.” A Swedish champion’s hand is “feud-calloused,” while the wyrm’s exhalation is “a hot battle-fume.” Grendel is “the hell-serf,” “the captain of evil,” “this corpse-maker mongering death.” His mother is “the wolf of the deep,” “the hell-dam,” “that swamp-thing from hell,” and “the tarn-hag” (all terms that would have come in handy when I was dealing with several of my teachers back in elementary school). And the dragon is “an old harrower of the dark,” “the hoard-watcher,” “the vile sky-winger,” and “the old dawn-scorching serpent.”

The sheer specificity of a line like “They collected their spears in a seafarer’s stook, a stand of grayish tapering ash,” builds Heorrrenda’s world as it has never been built before, while “But the Lord was weaving a victory on his war-loom for the Weather-Geats” melds the pagan and the Christian to fascinating effect. “God-cursed Grendel” comes “greedily loping,” and later, after his “splayed hand” has been repurposed as a trophy “under the eaves” Heaney makes sure we’re aware “Every nail, claw-scale and spuir, every spike and welt on the hand of that heathen brute was like barbed steel.” He probably has prior commitments that would keep him from writing any Sword-and-Sorcery of his own, but were he to do so, he’d be his own best Frazetta.

Perhaps a sneaking satisfaction can be found in the fact that, as John D. Rateliff reminds us, “Beowulf’s exploits may be retold in magnificent English verse, but take place far, far away back in the old country; it is English but not of England.” For irredentists with genetic ties to the much-vexed Celtic fringes of the British Isles, the poem is moving where a hypothetical epic lionizing the sons of Hengist and Horsa as they subjugate or ethically-cleanse the Britons would only estrange. And what of Heaney himself, in his own words “sprung from an Irish nationalist background and educated at a Northern irish Catholic school”? What business has a poet who “learned the Irish language and lived within a cultural and ideological frame that regarded it as the language which [he] should by rights have been speaking but which [he] had been robbed of” at King Hrothgar’s court? Heaney answers that question, coruscatingly, while justifying his use of the word “bawn”:

In Elizabethan English, bawn (from the Irish bó-dhún, a fort for cattle) referred specifically to the fortified dwellings which the English planters built in Ireland to keep the dispossessed natives at bay, so it seemed the proper term to apply to the embattled keep where Hrothgar waits and watches. Indeed, every time I read the lovely interlude that tells of the minstrel singing in Heorot, just before the first attacks of Grendel, I cannot help thinking of Edmund Spenser in Kilcolman Castle, reading the early cantos of The Faerie Queen to Sir Walter Raleigh, just before the Irish burned the castle and drove Spenser out of Munster back to the Elizabethan court. Putting a bawn into Beowulf seems one way for an Irish poet to come to terms with that complex history of conquest and colony, absorption and resistance, integrity and antagonism…

(Those kerns and gallowglasses who chased Spenser out of Munster were advance avengers for all of us who’ve toiled through even part of The Dairie Queen, as we called it sotto voce in a college seminar.)

Introducing his excellent 1957 prose translation, David Wright alluded to the poem’s “aura of overhanging catastrophe.” Throughout this monster-swarmed tale there are worse things waiting, worse because human. So, too, is Howard’s Hyborian Age brought low not by Xaltotun of Acheron with his malisons and cantrips, but by Gorm of Pictland. With a nod to the fate the actual manuscript did not entirely escape in 1731, I imagine the poem as a tapestry or pre-paper attempt to map the Old North on animal-skin, with flames licking at the edges all the while. No sooner have we been told of the construction and adornment of the “gold-shingled and gabled Heorot, then the poet’s smoke-detector goes off:

The hall towered,

its gables wide and high and awaiting

a barbarous burning. That doom abided,

but in time it would come: the killer instinct

unleashed among in-laws, the blood-lust rampant.

Beowulf is as preoccupied with bloodfeud and bodycount as Howard’s “The Man on the Ground” or “Red Nails.” Hwaet, or listen, to the last man standing of “the high-born race” whose riches will become the dragon’s hoard. His people “ruined in war,” he voices a lament as haunting as that given to Miranda Otto to sing at the funeral of the orc-hewn prince Théodred in Peter Jackson’s The Two Towers: “No trembling harp, no tuned timber, no tumbling hawk swerving through the hall, no swift horse pawing the courtyard.” All of this culminates in the vulnerability of the Geats, now bereft of Beowulf, at poem’s-end. The campfire of their warrior-king’s heroism has gone out, and the eyes of the surrounding Franks and Swedes burn balefully in the cold dark.

Neil Gaiman contributes an introduction to Caitlín R. Kiernan’s novel, arguing “Beowulf has long since left the endangered species list and begun to breed in many variants,” among which he lists “a science fiction version” (approach with extreme caution) and “a retelling in which Grendel is a tribe of surviving Neanderthals” (John McTiernan’s bravura Thirteenth Warrior). 2005 brought Beowulf and Grendel, a film the Icelandic sea-cliff locations of which were so stunning as to overpower any reservations about content — the pre-300 Gerard Butler does himself proud as Beowulf. And maybe something Seamus Heaney says in his introduction, where he almost seems to be scrying the performance-capture animation of the Zemeckis/Gaiman project, can be pressed into service as the 2007 movie’s best-case scenario:

…Or we can equally envisage it as an animated cartoon (and there has been at least one shot at this already), full of mutating graphics and minatory stereophonics. We can avoid, at any rate, the slightly cardboard effect which the word “monster” tends to introduce, and give the poem a fresh chance to sweep “in off the moors, down through the mist bands” of Anglo-Saxon England, forward into the global village of the third millennium.