A Century of L. Sprague de Camp, 1907-2007

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

posted by Leo Grin

Print This Post

Print This Post

Over at the D for de Camp Yahoo! discussion group, November 27, 2007 was like any other day. A few posts griping about this or that, nothing much going on. Astoundingly, in that disturbing silence quietly passed the centennial of the man that the group was ostensibly created to honor. L. Sprague de Camp would have been a hundred years old today — and not a single one of his most ardent fans noticed. Contrast that with REH’s dynamic 2006 centennial chock full of a solid year’s worth of celebratory events, honors, and journalism, and one begins to perceive how empty the de Campian gas tank has become. There’s simply no excuse for such a collective, stinging slap applied to the face of a late science fiction grandmaster. Pathetic doesn’t begin to adequately describe it.

Well, just because the milch cows who serve as his modern admirers have nothing to say is no reason for The Cimmerian to remain mute. De Camp had a hand in Robert E. Howard publishing and fandom for decades, and even accepting the harsh critical judgments of history doesn’t preclude honoring him for the vast amount of indisputable good he accomplished in the field.

I can recommend de Camp’s autobiography Time and Chance, for it clears up a lot of questions about the man and his motivations. Years ago, the first thing I was struck by after wading through its 400+ often charming pages is how barren de Camp was of any inclination towards the pose of artist. As he rolls through his life, highlighting what he thinks is important, we get hundreds of facts, jokes, anecdotes — but not a single expression of writing as a passion or a high calling, of wanting to use his stories to express something important to him. Compare Time and Chance to the collected thoughts of writers like REH and HPL, men who obsessed agonizingly over What It All Meant and how they would be judged (or ignored) by posterity, whether they would ever make their mark as an artisan of real merit, especially judged by their own rigorous standards, the standards of fiercely literary and individualistic prophets of imagination.

To de Camp, writing was a fun and fulfilling job, playtime, and he wasn’t the least bit interested in agonizing about any aspect of the creative process. Indeed, he thought the very idea absurd. About the closest he came to fathoming a purpose greater than a paycheck was when researching and publishing The Great Monkey Trial, still a valuable entry in the debate over evolution versus divine creation — Time and Chance shows de Camp eager to sock it to people he perceived as ignorant fundamentalists. His disdain for Scientology also prompted him towards genuine caring for getting somewhat heartfelt ideas on paper and out to readers. But overwhelmingly writing was a paycheck and nothing more. Howard used to make the same sorts of claims, that he was only in the writing game for the money and the freedom — the insincerity of those protestations is still glaringly apparent today. Howard cared, and deeply. He hacked it out when tired or capitalizing on a hot character, but always he came back, was dragged back, to his passions and themes. In de Camp’s long and detailed biography there isn’t a single attempt by him at addressing his career on this level. It’s all contracts and deadlines and what characters were inspired by what real-life personages met on trips to Europe or the Middle East. This lack of the deeper creative impulse is central to any understanding of the man and his legacy.

De Camp often was amazed that Howard and Lovecraft fans were so enraged by his commentary when all he was doing was analyzing facts and telling the unvarnished truth, to his mind exactly what a good biographer should do. For those readers who are only familiar with Dark Valley Destiny, one comes away from Time and Chance seeing that de Camp’s constant backhanded belittlement of REH had its roots not so much in a anti-Howard vendetta but in the unalterable personality of the biographer. It’s illuminating to see how, throughout its pages, de Camp psychoanalyzes himself and his friends and family with all the pedantic zeal and superior airs that he brought to his studies of REH and HPL. Phobias, personality faults, insignificant mistakes and misunderstandings — are all dissected in the detached, psuedo-scientific, hypercritical fashion that readers of his REH writings are so familiar with.

In the end, one understands why de Camp was so mystified at the rage expressed by his critics: this mode was simply the way he thought and operated. The apparent scorn and disdain for Howard’s life and times was, aside from a general aversion to Texas and the gun-totin’ south it represented, merely the byproduct of de Camp’s intelligent but often myopic mind. I came away from Time and Chance thinking about the film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, specifically the memorable statement that Ferris’ buddy Cameron, “is so tight that if you stuck a lump of coal up his ass, in two weeks you’d have a diamond.” Sprague did the best he could with the tools God granted him, and if we are to sympathize with and strive to understand Robert E. Howard’s many faults and foibles, we must grant de Camp the same courtesy.

What too often goes unmentioned these days is that de Camp’s best was often quite good indeed. Even if the Lancers are anathema to you, it’s nigh impossible not to admire de Camp’s many trips around Texas and indefatigable letter writing, all part of his quest to amass an invaluable collection of scholarship about REH, most of it stuff that would have been lost forever had he not made the effort. Thus, left to us are hundreds of pages of material containing priceless vignettes of Howard in his element and among his friends. A number of de Camp’s current detractors were (unlike me) adults and in the Howard fandom/scholarship arena during those years, yet none went as far as de Camp, who not only gained all of this knowledge but delivered it to fans in the form of a legitimate, full-length biography. In his own imperfect (and, admittedly, often infuriating) way, he helped drag Howard out of the mists of the forgotten past and into the heads and hearts of modern fantasy readers.

That so much of his work is in need of reinterpretation and rebuttal is unfortunate, granted. But again: de Camp did the best he could given his personality and mental makeup, and he left all of that raw data to later biographers so that they may use it to form their own evaluations. Everyone who writes about Robert E. Howard owes de Camp a major debt of gratitude for the Herculean efforts he undertook on behalf of REH scholarship. I don’t use the word “Herculean” here lightly — as someone who has traveled to Texas on Howard-related research expeditions numerous times, I know firsthand how expensive, exhausting, and difficult they can be. I also know how sad it is to barely miss out on getting an interview because of death cheating us out of it. Whenever I contemplate the cache of materials de Camp methodically collected, or sift through the small percentage that I’m lucky enough to have copies of, I am quietly impressed and forever thankful for the crosses he bore. For this alone, de Camp deserves a place of honor among Howardists.

But over the years de Camp did much more. He was instrumental in attracting a collective of Howard fans that centered around the magazine Amra, and that met at various cons and gatherings throughout the ’50s and ’60s. Over the years he lured all sorts of people, many of them revered professionals, into going on record about REH in various contexts. It’s hard to resist the notion that this helped firmly anchor REH at the center of the burgeoning fantasy market of the 1960s. The exact degrees and results of these ministrations are endlessly arguable, but the list of magazines, anthologies, book introductions, and fanzine articles that de Camp impregnated with a Howardian presence is formidable. I also appreciate that he was an honorary member of REHupa for so long, as during his lengthy tenure in that position he wrote many letters explicating his thoughts on a host of issues that continue to fascinate modern Two-Gun scholars. With his REHupan critics hammering him on a number of fronts throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, the old warhorse continued to slug it out, providing us with lots of information that would otherwise never have come to light.

Then of course there is his enormous non-Howard production in the science, historical, and science fiction fields. Like most authors, the majority of de Camp’s literary output is destined for obscurity. Few scriveners achieve what Howard has, where every scrap of writing — even the junk — is considered precious (at least on a thematic, scholarly level) and hence gets preserved in print in omne tempus. In de Camp’s case several of his non-fiction volumes, such as the ones about Atlantis and ancient history and mythology, will remain useful and exciting to lovers of real-life adventure and discovery. A few of his science fiction novels like Lest Darkness Fall will remain memorable (albeit dated) classics. His Incompleat Enchanter stories may yet achieve a sort of semi-immortality in various reprintings. Regardless of the publishing specifics, he’ll always be remembered as a standout member of the Campbellian pulp era, and no one can ever take the awarded title of sci-fi grandmaster away from him. All of that is far more than most of us will ever accomplish in the fantasy or sci-fi fields, and collectively it’s an achievement that demands no small amount of respect.

The feeble protestations of his partisans notwithstanding, de Camp’s grip on the Howard field is long gone. For well over a decade now Howard publishing has been dominated by what can loosely be referred to as an anti-de Camp faction. These are a group of guys who endured thirty years of his near-stranglehold on the perception of Howard in the broader fantasy marketplace, and who are now intent on methodically undoing the damage wrought over decades of judging REH by oftentimes reductive, frivolous, and catty standards. Whenever there is a call for someone to step up and say something about the creator of Conan, it is inevitably the new guard who now gets contacted, with de Camp’s old acolytes relegated to an embarrassing, impotent bystander status. But now that de Camp’s objectionable machinations have been put to the sword and buried in unmarked graves, it’s important to preserve the good he brought into the field and give it its proper place and measure.

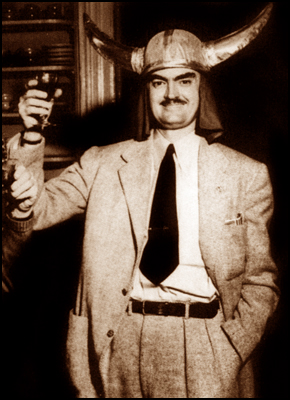

There will likely be no centennial celebration, aside from whatever sparsely attended rogue con panels get assembled by caponized de Camp cultists. But perhaps the more mature and less vindictive among us can see fit to raise a glass this cold November evening to a man who had one of the all-time longest careers in fantasy, a veteran now resting in Arlington, who made the most of a long fruitful life. He left us with a lot to lament, alas, but also a lot to admire and appreciate. Happy 100th birthday Sprague, you wily old pulpster.

Meanwhile, we still have the embarrassing spectacle of de Camp’s biggest fans forgetting to mark his centennial with anything greater than utter silence. This has put me in a somewhat uncharitably sour mood: not since I quit the board of The Dark Man in December of 2003 have I been so disgusted at the hapless, witless performance of a group of colleagues. I’m so thoroughly revolted, in fact, that I’ve come to an ad hoc decision, one that feels not only appropriate but strangely purifying, like a good flea bath or delousing: I’m going to remove the D for de Camp group from my list of links on TC‘s blogroll. I originally put it up as a tangential link to REH, mostly out of a sense of charity towards my good buddy and frequent Cimmerian contributor Gary Romeo. But damn — friendships aside, I see no reason to funnel Cimmerian readers towards a congregation that reeks of such bovine stupidity that it misses the most important de Camp milestone of this century. If they can’t even work up the energy to mention his centennial, what good is the forum at all? Maybe D is for dumbasses? For shame, halfwits, for shame.

AND: for a short but reasonable analysis of de Camp’s influence on Lovecraft fandom, visit this post at the Grim Reviews blog.

UPDATE: more de Camp opinions can be found at NRO’s The Corner, at Instapundit, at CoolSciFi, and at Light Seeking Light. I can’t disagree with Glenn Reynolds’ take: had I known anyone outside of Robert E. Howard fandom cared, I would have certainly skewed my post for a more general audience. But in the end that’s the point: none of the people out there who claim longstanding fondness for de Camp’s writing bothered to remember his centennial, not even the fans who populate the lone discussion forum dedicated to his work. It took a Robert E. Howard scholar — still nursing wounds from de Camp’s shoddy editing and risible biographical treatment of the Texan — to step up and give him a shout out. Pretty sad.