“In fact, I’m something of a gourmand — I believe you spell it that way.” Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, ca. December 1932.

Howard Days in Cross Plains is just around the corner. Thus and therefore (and especially since I’m unable to attend this year), I find myself yearning for fare of the Texan persuasion. My first trip to Howard Days (in 2006), I stayed over in Dallas the night before. One of my Texan cousins steered me to a little hole-in-the-wall called Lee Harvey’s in a fairly disreputable quarter of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. Excellent burgers, cold beer and billiards (and discussions regarding Dan Brown and the Knights Templar) made for a memorable evening.

Soon after pulling up to the Alla Ray Morris Pavillion in Cross Plains the next day, I savored the hearty fare purveyed by Joan McCowen and the other estimable members of Project Pride. Nachos and chili just do a pilgrim’s soul good, I must say.

The gustatory highpoint (figuratively and literally) of both my trips to Robert E. Howard’s hometown would have to be the Saturday night barbecues at the Caddo Peak Ranch. Do not breath a word of this to my Kansan brethren, but Texan BBQ has it all over KC barbecue. Marjorie Middleton (and many others) put on a mouth-watering spread of Texan proportions, with attendant Lone Star hospitality.

However, my trips to Cross Plains were but the latest of my personal forays into the splendrous fields of Texan cuisine. Ever since the Christmas of ’76, I’ve visited Texas and sampled its culinary wares. Having relatives in the Dallas area helps mightily in that regard. Probably my most memorable visit (in regards to Texan food) was in 1980. In the short week I was there, my uncle took me to the legendary Tolbert’s Chili Parlor (founded by a Texan with the most Howardian moniker of “Frank X. Tolbert”) and a Tex-Mex restaurant (name unremembered) which served a delectable (and still unknown-beyond-Texas, at the time) dish called “fajitas”. Yeah, I thought my Uncle Gary Bradbury was pretty cool.

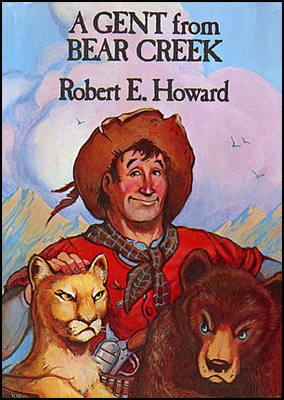

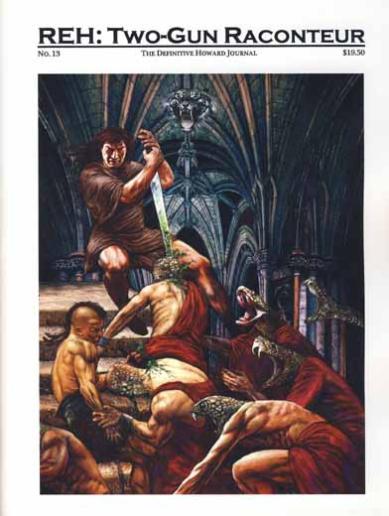

Robert E. Howard was, by his own admission, a bit of a “gourmand.” Judging from what Rusty Burke cites in “The Gustatory REH,” Howard was not laying claim to a false title. For a small-town Central Texas boy who reached manhood before the Second World War, REH’s tastes in food were wide-ranging (indicative of his far-reaching studies in numerous other areas). In his letters, Howard speaks of his appreciation for Mexican, Italian, German, Creole (and, by extension, Caribbean) cuisines. Such might be more likely expected (in that era) from a well-heeled sophisticate born to a more cosmopolitan clime.

That said and noted, I believe Robert E. Howard would be highly pleased by the latest (July 2009) issue of Saveur magazine, which is on newsstands as we speak. Most fortuitously (considering that Howard Days are just around  the corner), the editors and writers of Saveur (several of whom have Texan connections) decided to dedicate their most recent issue to the food-ways of the Lone Star State. To my knowledge, Saveur has never devoted an entire issue, cover to cover, to just one region, state or country (depending on whether you’re a Texan or not, the “state” or “country” designation may be problematic).

the corner), the editors and writers of Saveur (several of whom have Texan connections) decided to dedicate their most recent issue to the food-ways of the Lone Star State. To my knowledge, Saveur has never devoted an entire issue, cover to cover, to just one region, state or country (depending on whether you’re a Texan or not, the “state” or “country” designation may be problematic).

So, a singular honor has been granted to Texan cuisine by the finest cooking magazine in print (which Saveur is, in my opinion). Several chapters in the July 2009 issue relate specifically to Robert E. Howard’s opinions and tastes. Here’s a few… (Continue reading this post)

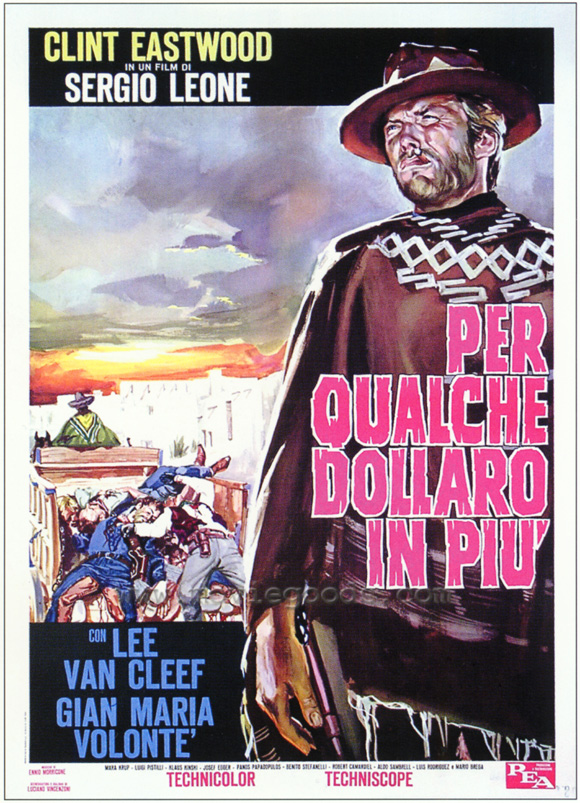

fan. I was probably viewing John Wayne flicks in the cradle. My specific knowing of whom John Wayne was, without a doubt, began when I watched a broadcast of True Grit right before I entered the double-digit stage of my lifespan.

fan. I was probably viewing John Wayne flicks in the cradle. My specific knowing of whom John Wayne was, without a doubt, began when I watched a broadcast of True Grit right before I entered the double-digit stage of my lifespan. the corner), the editors and writers of Saveur (several of whom have Texan connections) decided to dedicate their most recent issue to the food-ways of the Lone Star State. To my knowledge, Saveur has never devoted an entire issue, cover to cover, to just one region, state or country (depending on whether you’re a Texan or not, the “state” or “country” designation may be problematic).

the corner), the editors and writers of Saveur (several of whom have Texan connections) decided to dedicate their most recent issue to the food-ways of the Lone Star State. To my knowledge, Saveur has never devoted an entire issue, cover to cover, to just one region, state or country (depending on whether you’re a Texan or not, the “state” or “country” designation may be problematic).