The poetry of Robert E. Howard has long been known for its martial splendor and potent battle imagery, but what is most striking to me is how successfully he managed to get into the heads of soldiers and warriors, and how completely he was able to immerse himself (and hence the reader) into the real-life thoughts and feelings of both killers and victims, the battle-hungry and the battle-weary. There’s a difference between merely sprinkling appropriate adjectives into your poetry and capturing the essence of the struggle of warfare in all its harrowing details and viewpoints. In his best work Howard achieves this again and again.

Consider this poem, written by Howard a full decade before the onset of World War II, and yet encapsulating perfectly the civilizational battle for supremacy that was about to explode upon the world:

“Little Brown Man Of Nippon”

Little brown man of Nippon

Who apes the ways of the west,

You have set the sword on your standard,

And the eagle on your crest.

Little brown man of Nippon,

You have dreamed a deadly dream;

You have waked the restless ravens

And the rousing vultures scream.

Oh, lines of an unborn empire,

Foam of a rising flood,

Your bones shall mark the borders,

The tide shall be your blood.

Little brown man of Nippon,

Though the star of the West be set,

And the last of the fair-haired strew the field

Where East and West be met —

Though you herd us down like cattle,

And hew us down like corn,

Our blood shall drown your vision

Of the empire yet unborn.

In utter desolation, and despair

At the end, on a blackened hill,

You shall sit and view your empire,

Broken and charred and still.

The beams of shattered houses,

Reared stark against the sky,

And fields wherein, for waving grain,

Long waves of dead men lie.

We will set the torch with our own hands

To wall and roof and spire;

We will cut the throats of our women,

And feed our babes to the fire;

We will fling our naked bosoms

Against your bloodied steel;

As you tread us under, dying,

Our teeth shall rend your heel.

But, little brown man of Nippon,

Should the dice fall otherwise,

And the gods of the fair-haired triumph

When the battle-dawns arise —

We will give your flesh to the sea-gulls

And your cities to the flame,

Till the world forgets your visions,

And the years forget your name.

Over your island empire

Shall our steel-clad squadrons fly

Till the land lies black and silent

Under a flame-ripped sky.

Till the hungry wolf goes slinking

Along your shattered streets,

And the kite in your ruined palace

Tears at the crimson meats.

And over the crimson gutters

Which infant bodies choke

The raven flaps and strangles

In the drifting shreds of smoke.

No plough shall break your valleys,

No song shall rouse your hill —

Still and silent the ploughmen,

The singers silent and still.

And your nation’s only emblem,

Oh, man of the crimson dream —

Save corpses in the broken streets

And the death-fires’ baleful gleam —

Shall hang at the prow of a cruiser,

That furrows the flying foam,

Bearing the spoils of conquest

To the fair-haired people’s home.

Shall hang at the prow of a cruiser,

Grinning and dripping red,

The price of a dream of empire —

Little brown man, your head.

The dwelling on the savagery and the tenacity of both sides, and the pain and bloodshed that would accompany any war between the powers of East and West, demonstrate striking parallels between Howard’s poetry and the verse written around the same time by actual soldiers in the field. On the web you can read Larry Richter’s first ‘zine for REHupa from many years ago, where he argues that George S. Patton shared many qualities with Howard when writing his own ghostly battle poems. It’s a compelling comparison; who can forget George C. Scott stopping at a line of Roman ruins in the film Patton and giving a speech seemingly written by Howard’s reincarnation hero James Allison?

“The Carthaginians defending the city were attacked by three Roman legions. The Carthaginians were proud and brave, but they couldn’t hold. They were massacred. Arab women stripped them of their tunics and their swords and lances. The soldiers lay naked in the sun. Two thousand years ago. I was here.”

Men who share Howard’s predilections are plentiful for those who keep a lookout for them. I recently came across another soldier-poet in the Howardian mold. In late 1941, Lt. Henry G. Lee was a twenty-seven-year-old recruit serving with the Philippine Division of the US forces. Raised in Pasadena, California, he was an amateur versifier who wrote regularly into a journal about life and battle. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, realizing that he was about to be plunged into the thick of bloodthirsty war, Lee penned the following poem:

“Prayer Before Battle (To Mars)”

(December 8, 1941)

Before thine ancient altar, God of War,

Forlorn, afraid, alone, I kneel to pray.

The gentle shepherd whom I would adore,

Faced by thy blazing plaything, slips away.

And I am drained of faith — alone — alone.

Who now needs faith to face thy outthrust sword,

Bereft of hope, turned to pagan to the bone.

I kneel to thee and hail thee as my Lord.

From such a God as thee, I ask not life,

My life is forfeited, the hour is late.

Thou need not swerve the bullet, dull the knife.

I ask but strength to ride the wave of fate.

And one thing more — to validate this strife,

And my own sacrifice — teach me to hate.

Teach me to hate. Those of you who have read my essay “The Reign of Blood,” in The Barbaric Triumph know that, in my opinion, it would be difficult to conjure a more Howardian sentiment than that.

Months later — with the islands under assault by the Japanese, and certain defeat, capture, and torture looming — Lee and the rest fought bravely alongside Philippine scouts, who he immortalized in another stirring poem:

“To the Philippine Scouts”

Philippine Scouts-N. Luzon, S. Luzon, Abucay, Moran, The Points, Toul Pocket, Mt. Samat, Corregidor (December 8, 1941-May 8, 1942)

The desperate fight is lost; the battle done.

The brown, lean ranks are scattered to the breeze

Their cherished weapons rusting in the sun

Their mouldering guidons hidden by the leaves.

No more the men who did not fear to die

Will plug the broken line while through the din

Their beaten comrades raise the welcome cry

“Make way, make way, the Scouts are moving in.”

The jungle takes the long-defended lines

The trench erodes; the wire rusts away

The lush lank grasses and the trailing vines

Soon hide the human remains of the fray.

The battle ended and the story told

The blood-smeared leaves of history begin

To open to the Scouts, as they unfold

The little tired soldiers enter in.

The men who were besieged on every side

Who knew the disillusion of retreat

And still retained their fierce exultant pride

And were soldiers — even in defeat,

Now meet the veterans of ten thousand years

Now find a welcome worthy of their trade

From men who fought with cross bows and with spears

With bullet and with arrow and with spade.

The grizzled veterans Rome was built upon

The Death-head horde of Attila the Hun

The “Yellow Horror” of the greatest Kahn

The guardsmen of the first Napoleon

And all the men in every nameless fight

Since man first strove with man to prove his worth

Shall greet the Scouts as is their right —

No finer soldiers ever walked the earth.

And then the Scouts will form to be reviewed

Each scattered unit now once more complete

Each weapon and each bright crisp flag renewed

And high above the cadence of their feet

Will come the loud clear virile welcoming shout

From many throats before the feasts begin

Their badge of honor mid their comrades rout —

“Make way, make way, the Scouts are moving in.”

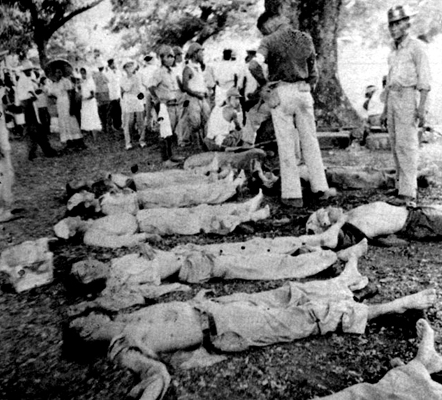

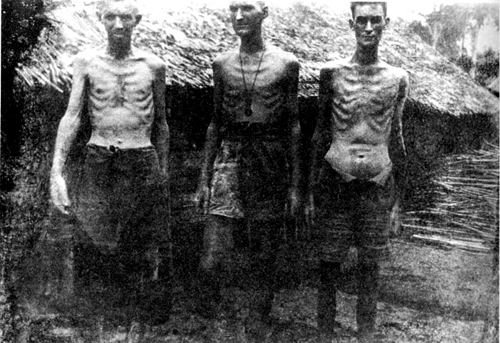

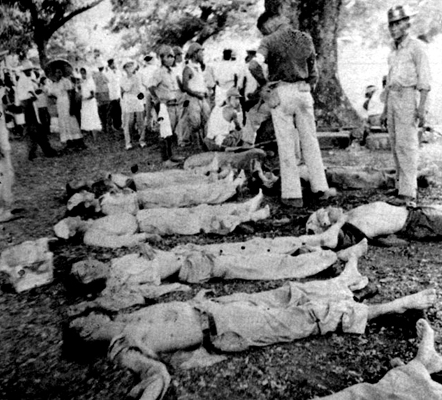

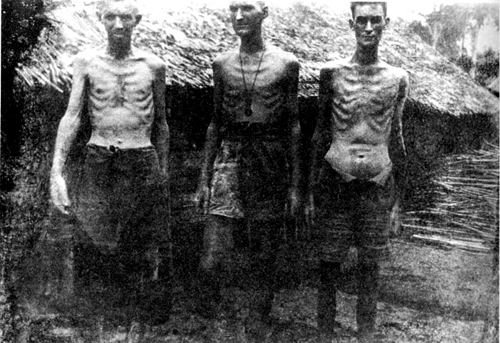

Starving and without aid of any kind, Lt. Lee and his men finally surrendered on April 9, 1942 with the rest of the Americans, and became prisoners of the fearsome Japanese. He was allowed to send a single postcard to his family with his signature on it, and then spent the next three years in hellish conditions in an Imperial prison camp. The Japanese had never signed the Geneva Conventions, and they subjected their charges to a host of horrors.

During that time, Henry Lee continued to surreptitiously record poems in his now-hidden journal, forging a series of very poignant and emotional paeans to warfare and prison that Howard fans will find very familiar.

“Fighting On”

I see no gleam of victory alluring

No chance of splendid booty or of gain

If I endure — I must go on enduring

And my reward for bearing pain — is pain

Yet, though the thrill, the zest, the hope are gone

Something within me keeps me fighting on

“Death March”

So you are dead. The easy words contain

No sense of loss, no sorrow, no despair.

Thus hunger, thirst, fatigue, combines to drain

All feeling from our hearts. The endless glare,

The brutal heat, anesthetize the mind.

I can not mourn you now. I lift my load,

The suffering column moves. I leave behind

Only another corpse, beside the road.

Howard’s own fascination with capture, torture, and escape, with the evil that men do to those under their bloody thumbs and bootheels, finds echo in Lt. Lee’s lines about an execution, perhaps one of many which he himself witnessed during those grim years:

Red in the eastern sun, before he died,

We saw his glinting hair; his arms were tied.

There by his lonely form, ugly and grim

We saw an open grave waiting for him.

We watched him from our fence, in silent throng,

Each with the fervent prayer, “God make him strong.”

They offered him a smoke, he’d not have that,

Then at his captor’s feet he coldly spat.

He faced the leaden hail, his eyes were bare;

We saw the tropic rays glint in his hair.

What mattered why he stood facing the gun?

We saw a nation’s pride there in the sun.

How desolate must his soul have become after three years of such misery, not knowing if he would ever be rescued, or whether the next crack of a pistol would signify his own death. By 1944 the war was going America’s way, but to the prisoners victory and freedom were but a stale dream. Three years to the day after his Pearl Harbor-inspired poem, Lt. Lee wrote another that gives us an idea of how much he had changed by that time:

“Three Years After”

(December 8, 1944)

“Teach me to hate,” I prayed — for I was young,

And fear was in my heart, and faith had fled.

“Teach me to hate! for hate is strength,” I said

“A staff to lean on.” Thus my challenge flung

Into the thunder of the clouds that hung

Cloaking with terror all the days ahead —

“Teach me to hate — the world I loved is dead;

Who would survive must learn a savage tongue.”

And I have learned — and paid in days that ran

To bitter schooling. Love was lost in pains,

Hunger replaced the beauty in life’s plan,

Honor and virtue vanished with the rains

And faith in God dissolved with faith in man.

I have my hate! But nothing else remains.

Had Howard lived, would he have reached a similar state of mind? Would he have perhaps fought in that very war, and experienced its horrors for himself? How would it have affected his fiction? We’ll never know, but in the writing of Lt. Lee we see what might have been, a man who sees the darkness and the unadorned ferocity of the human soul in ways seldom expressed in this comparatively tender age.

Howard didn’t have war to contend with, but he was engaged for all his life in a war of the mind and of the soul, a battle against the scourges of depression, the pulp marketplace, and the hatred directed at him by the very town in which he lived. Howard was in a prison camp of sorts, too, and with no way out. And it eventually killed him every bit as dead as if he had fallen under the bayonets of the Japanese.

As it happened, there was no escape for Henry Lee, either. In late December 1944, he was put on a transport ship and sent to Japan as slave labor. Before leaving, he hastily dug a hole under a prison hut and buried his journal of poems, hoping that someday in the future — as a free soldier in a victorious American army — he might come back and retrieve it. En route to Japan, an American plane caught sight of the unmarked boat and unleashed a hail of bombs, sending the transport to the bottom of the ocean — and the young Poet of Bataan along with it. Lee was thirty years old — the exact age Howard was when he met his own violent end. Two young poets possessed of searing thoughts and a preternatural sensitivity for the power of words and rhyme, both lost to the worms and the ages.

If there is a happy ending to be found in either man’s story, it is that neither has been forgotten. In Howard’s case, we ultimately have people like Glenn Lord, L. Sprague de Camp, Novalyne Price Ellis, and Rusty Burke to thank for that. As for Lee, on January 30, 1945 the prison where he had spent three years, Camp Cabanatuan, was liberated by the Sixth Ranger Infantry Battalion led by Lt. Col. Henry A. Mucci, who had audaciously led his men far behind the Japanese front and taken the enemy unawares. This unbelievable action — depicted in the book Ghost Soldiers: The Epic Account of World War II’s Greatest Rescue Mission, and later in the 2005 film The Great Raid — resulted in the rediscovery of Lee’s buried journal, and subsequently (in 1948) the publishing of his poems for posterity in a volume called Nothing But Praise. The Great Raid had come a few precious weeks too late to save Henry Lee, but it managed to save his life’s work: a small dirt-encrusted journal containing faded poetry scribbled out with such emotion that it may as well have been penned in blood.

Something tells me that Robert E. Howard and Lt. Lee would have made fine friends. Both understood that speaking truth often requires a savage tongue, and that there is honor and succor to be found in struggle and warfare and death. The worlds of history and poetry are both the better for having known them.

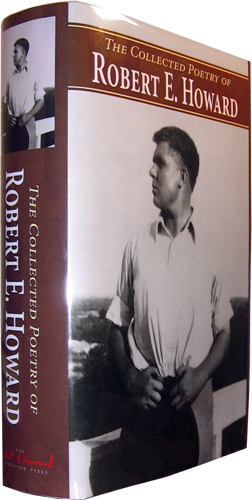

Finally received my copy of The Collected Poetry of Robert E. Howard, and boy, was it ever worth the wait. At 728 [redacted]-edited pages and well over seven-hundred poems, it’s a monster of a collection. Toss in the great design and layout courtesy of Jim Keegan, the fine workmanship of the Smythe-sewn signatures, and the inclusion of Steve Eng’s classic essay on Howard’s poetry as the book’s introduction, and we finally have the definitive one-volume, casebound edition of REH’s verse that we have been waiting decades for.

Finally received my copy of The Collected Poetry of Robert E. Howard, and boy, was it ever worth the wait. At 728 [redacted]-edited pages and well over seven-hundred poems, it’s a monster of a collection. Toss in the great design and layout courtesy of Jim Keegan, the fine workmanship of the Smythe-sewn signatures, and the inclusion of Steve Eng’s classic essay on Howard’s poetry as the book’s introduction, and we finally have the definitive one-volume, casebound edition of REH’s verse that we have been waiting decades for.

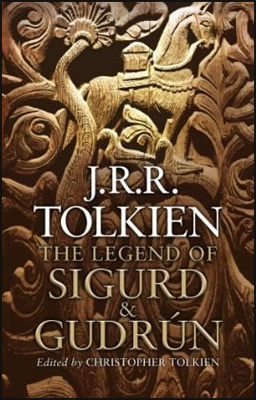

We live in halcyon days, my friends. Sure, there’s a global “economic downturn” grinding all and sundry ‘neath its leaden wheels and there is a possible influenza pandemic looming (or “lowering,” as REH might say), but we aficionados of the works of Robert E. Howard and John Ronald Reuel Tolkien have much to celebrate in the many coming months, gloom n’ doom notwithstanding.

We live in halcyon days, my friends. Sure, there’s a global “economic downturn” grinding all and sundry ‘neath its leaden wheels and there is a possible influenza pandemic looming (or “lowering,” as REH might say), but we aficionados of the works of Robert E. Howard and John Ronald Reuel Tolkien have much to celebrate in the many coming months, gloom n’ doom notwithstanding.