It’s easy to be a morning person when one happens upon pleasant surprises like the following in the New York Times:

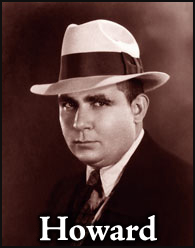

In May 1934, two years before he killed himself in the driveway of his home in Cross Plains, Tex., Robert E. Howard published one of the finest adventures of his most famous character: the warrior, thief, swashbuckler and king called Conan the Cimmerian.

In the story, “Queen of the Black Coast,” Conan lounges in moonlit reverie on the deck of a galley beside the pirate queen Bêlit and reveals his elemental, live-for-the-moment spirit.

“Let me live deep while I live,” he says. “Let me know the rich juices of red meat and stinging wine on my palate, the hot embrace of white arms, the mad exultation of battle when the blue blades flame and crimson, and I am content. Let teachers and priests and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.”

Conan is no hero. The best Conan stories end not in triumph but in an ambiguous, almost melancholy recognition that righteousness is scarce, perhaps even irrelevant. Conan’s world is not one of grand struggles between good and evil. Rather it is a world of avarice, of treachery, of raw power, slavery, embraced passions and ancient secrets best kept from man.

That’s from “At Play in a World of Savagery, but not This One,” by Seth Schiesel. Mr. Schiesel’s piece is ostensibly a review of Funcom’s Age of Conan, and yet he chooses to lead with four accurate and insightful paragraphs about Robert E. Howard and Howard’s Conan (“Conan the Barbarian,” may his fur diaper chafe him, is nowhere to be found). Manna from heaven (Mitra or perhaps Ishtar, certainly not Crom) made all the tastier because one of the most notorious of all hatchet jobs on the reason we blog here, “Superman on a Psychotic Bender” by H. R. Hays, appeared in the New York Times back in 1946. We’ll accept Schiesel’s review as a first step toward atonement.

Regrettably, he sees fit to include a facile comparison between Tolkien and Howard: “While Conan hacked and slashed his way through a decaying, darkening world, Bilbo, Aragorn, Frodo and Gandalf became paragons of virtue…” Seems to me the Middle-earth of the late Third Age, caught between Isengard and Barad-dûr, is decaying and darkening up a storm. Mr. Schiesel might also be gobsmacked by what the late First Age was like, and it’s now easier than ever before to learn, by reading The Children of Hà¹rin.

Still, at the moment I’m a delighted Howardist, not a touchy Tolkienist, and the review is further sweetened by several quotes from game designer Gaute Godager, who likens Conan to the archangel Gabriel marching into Sodom and Gomorrah (a Biblical precedent that just so happens to have also been very much on Sergio Leone’s mind in A Fistful of Dollars). Godager also says “Howard put Genghis Khan and the Mongolians in with the Romans and the Greeks, some Celts, and the sense of Africa pouring in a lot of this sense of darkness and put it on the stove, put the lid on and let it brew and simmer.” My only quibble with that would be that much of the darkness is Stygian, Acheronian, “Eastern” (the Master of Yimsha), or pre-human rather than “African.”

What really matters, though, is a signature passage from “Queen of the Black Coast” turning up in what still has a claim, albeit a somewhat shaky one, to being the newspaper of record. Very cool.