Saturday, August 16, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

In the article I recently posted surveying Sword-and-Sorcery since the Eighties, it was a particular pleasure to push the ornery-in-the-best-sense, refusing-to-consent-to-consensual-reality work of Matthew Stover as hard as I could. Stover’s latest novel will be throwing elbows on bookstore shelves this fall, and over at his blog he’s been musing about how, while the women who enjoy the adventures of Hari Kaine (an assassin as lethally talented at kingdom-decapitating as Gemmell’s Waylander) really, really enjoy them, a certain post-graduate studies quality makes demands that will at least partially exclude some readers:

The real problem with gathering feminine readership for the Acts of Caine, it seems to me, is that [Heroes Die, Stover’s first Caine novel] depends on an SFF-savvy reader — for it to have full effect, the reader should already be well-versed to the point of exhaustion with the various tropes that the story is twisting into less-familiar shapes. Which seems to be more of a guy thing, overall.

Make sure the woman you lend the book to has already read Conan and Bran Mak Morn, Elric and Hawkmoon and Fafhrd & Gray Mouser and the like, and I’m pretty sure she’ll like Caine.

This is a problem with male readership as well. As one editor at Del Rey told me:

“What stops Caine from being more successful is that he’s only accessible to people who are already hardcore fans. Write something ‘entry-level’ — not necessarily Harry Potter, but even more grown-up entry-level like most of Jonathan Carroll or Neil Gaiman, something where someone who knows nothing about SF and fantasy can enjoy it — and you’re golden.”

Unfortunately for me and my career, I’ve never been able to pull something like that together, outside of Star Wars.

(Continue reading this post)

Thursday, August 14, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

Speaking of Ernest Hemingway, whom Steve mentions in his last post, friend of The Cimmerian John J. Miller has a brand new piece on the Master and his fishing habits in The Wall-Street Journal. Miller’s interest is more than professional — he grew up in Michigan and recently vacationed “Up North” in Seney, where the Hemingway stories discussed take place.

Friday, July 25, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

[When Howard Andrew Jones writes about sword-and-sorcery and the desirability of “putting a new edge on an old blade,” it behooves those of us as protective of the subgenre as he is to pay attention, and perhaps pay him the compliment of trying to put our own thoughts in order. To that end, and with a bemused glance at a June 22 post by Gary Romeo, who never loses an opportunity to generalize about Howard purists even if he did lose the chance to celebrate the centennial of his nearest and dearest, I’m rolling out the following article, originally written in 2006 for an anthology that apparently could not be more snake-bitten were it to traipse barefoot through Stygia]

The subgenre of modern fantasy with which Robert E. Howard is nearly synonymous died down in the mid-1980s but did not die out. Far from it; sword-and-sorcery proved to be as difficult to kill as many of its protagonists. But before we can celebrate Howard’s legacy by following the subgenre’s fortunes for the last several decades, we need to establish what we mean by sword-and-sorcery. For starters, what is meant at least for the purposes of this article is an approach to heroic fantasy that became aware of itself when Howard decisively expanded on the promise and premise of Lord Dunsany’s 1908 story “The Fortress Unvanquishable Save for Sacnoth” with “The Shadow Kingdom” in 1929.

The verb “expanded” is chosen with no disrespect whatsoever intended toward Dunsany’s story; it is possible that during his much-debated involvement with sword-and-sorcery, L. Sprague de Camp never did the subgenre more of a favor than when he selected “The Fortress” for his anthology The Fantastic Swordsmen (1967).

(Here, on the other hand, Leo argues that the only place for poor old “Sacnoth” in an S & S muscle car is: the ejector seat)

(Continue reading this post)

Saturday, June 21, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

Over at his blog, Charles Saunders has just added an interesting new post on the influences driving the protagonist of his latest book of stories, Dossouye. Just click on the link and then click on “Blog.”

Monday, May 26, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

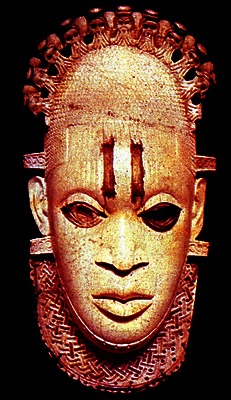

A champion is someone who gets up when he can’t. Charles Saunders, whose “Fists of Cross Plains” (which can be read at Damon Sasser’s REH: Two-Gun Raconteur website) is a blow-by-blow of a fanciful Robert E. Howard Heavyweight Championship staged, and ultimately upstaged by audience participation, in the Texan’s hometown, has earned that Dempseyism. The creator of Imaro of Nyumbani and Dossouye, she who was once an ahosi in the army of the Leopard King of Abomey, has had plenty of practice in shrugging off the slings, arrows, and belaying pins of outrageous publishing misfortune. Most recently, just as he promised in his TC interview last year, he has bounced back to his feet after being floored by the disappointment of Night Shade Books’ decision to give up on a relaunched Imaro series after just two installments, a Short Count to rival the infamous Long Count of the Dempsey/Tunney rematch. Saunders is now working with the most simpatico publisher he’s ever had, himself, and the first offering of that partnership is Dossouye, a “Sword-and-Soul epic” that can and should be ordered from lulu.com.

(Continue reading this post)

Sunday, May 25, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

Charles Saunders has started a blog, and so far the posts have been quite substantive and interesting. The latest is a rundown of some of the major influences for his S&S hero Imaro, and the overview covers a lot of ground, including several mentions of REH. He has a comment engine running, too, so you can talk back to him and start a discussion on the posts. Well worth a look.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

Cimmerian readers are aware of the intellectual battle that has been waged in The Lion’s Den about H. P. Lovecraft since the release of “Lovecraft’s Southern Vacation” in TC V3n2 (February 2006). One of that discussion’s prime participants, Graeme Phillips from England, has recently published the first issue of a new ‘zine dedicated to the man who was Providence. Titled Cyäegha, and produced in a run of sixty numbered copies, the first issue is dedicated to the Belgian Mythos writer Eddy C. Bertin and runs twenty-eight pages.

For a contents listing and ordering information, go here.

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

My copy of Dossouye is ordered and on the way, and I’ll have more to say about it another time. Until then, head over to Charles Saunders’ brand new website, complete with blog, links to interviews, and of course information on his new book.

Friday, April 11, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Any given year is a demonstration of mortality in action, but so far 2008 has been especially hellbent on inaugurating the afterlives of figures who had permanent luxury suites in the Tompkinsian pantheon: George MacDonald Fraser, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Fagles, and now Charlton Heston.

No sooner was I surfing the first wave of obituaries and career summaries than I was muttering and cursing. Everything else Heston did was being reduced to flotsam bobbing atop each half of the parted Red Sea, or dust beneath Judah Ben-Hur’s chariot wheels. It’s difficult to be objective about those movies because they became the Easter season equivalent of the Yule log, always on the TV screen in the background. When I try to watch either, it isn’t long before I wish someone had spiked the holy water. Oh, Ben-Hur retains some interest because of the involvement of Gore Vidal, Yakima Canutt, and a young assistant director named Sergio Leone, and the early scenes at the Egyptian court in The Ten Commandments are entertaining, mostly because of Yul Brynner’s seething Ramses (had he not gotten all that emoting out of his system, would he ever have been able to play the robot gunfighter in Westworld?) But I prefer Heston’s mid-career parts, when cracks in the Michelangelo-sculpted marble and verdigris on the gleaming bronze began to be detectable, so I was glad to find Manohla Dargis’ “The Man Who Touched Evil and Saved the World” in the New York Times: “My fondness for Mr. Heston can be traced back to the films I saw growing up, most important, his great dystopian trilogy, Planet of the Apes (1968), The Omega Man (1971), and Soylent Green (1973).” Had Ms. Dargis bethought her of how Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) ends, she might have reconsidered the second half of her tribute’s title, but I’m with her on the Dominus of Dystopia; whenever I read Howard’s “The Last Laugh” (an overheated discussion of which concludes an essay printed in TC V5n1), despite the probable Conanomorphism of the protagonist’s appearance, I imagine Charlton Heston, the last word in last stands and the first choice for the day after the end of the world.

(Continue reading this post)

Saturday, March 29, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Arma virumque cano…Robert Fagles, who unleashed what some of us consider the supremely Howardian gifts of intensity and immediacy on The Iliad (1990), The Odyssey (1996), and The Aeneid (2006), died this week. Died, save for the imperishable legacy that yet lives and will keep right on flying out of bookstores like the winged monkeys in The Wizard of Oz (er, that is, if they were noble and tragic).

The classicist Oliver Taplin wrote of the Fagles Iliad that “his narrative has real pace, it presses onward, leading the reader forward with an irresistible flow.” The speed of a cheetah, the spring of a leopard, the strength of a tiger, all in one translator/poet package. A fellow member of the Princeton faculty, Paul Muldoon, remembers Fagles as “a quiet man, diligent and decorous, yet one who was unexpectedly equal to the swagger and savagery of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey in a way no one had managed before him. It was as if two key texts of Western literature had been adapted by a director of Westerns like Leone or Peckinpah.” That, O Prince, is high praise indeed.

(Continue reading this post)