Little Lost, and Much Gained, In Translation

Saturday, March 29, 2008

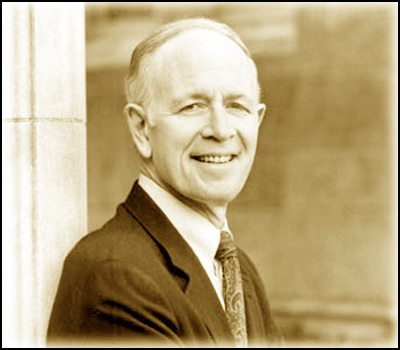

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Arma virumque cano…Robert Fagles, who unleashed what some of us consider the supremely Howardian gifts of intensity and immediacy on The Iliad (1990), The Odyssey (1996), and The Aeneid (2006), died this week. Died, save for the imperishable legacy that yet lives and will keep right on flying out of bookstores like the winged monkeys in The Wizard of Oz (er, that is, if they were noble and tragic).

The classicist Oliver Taplin wrote of the Fagles Iliad that “his narrative has real pace, it presses onward, leading the reader forward with an irresistible flow.” The speed of a cheetah, the spring of a leopard, the strength of a tiger, all in one translator/poet package. A fellow member of the Princeton faculty, Paul Muldoon, remembers Fagles as “a quiet man, diligent and decorous, yet one who was unexpectedly equal to the swagger and savagery of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey in a way no one had managed before him. It was as if two key texts of Western literature had been adapted by a director of Westerns like Leone or Peckinpah.” That, O Prince, is high praise indeed.

Writing in the darkest depths of the Forties, as the Third Reich’s Nacht und Nebel obscured and threatened to erase European civilization, Simone Weil responded with the 20th century’s most memorable observation about the first Western epic: “The true hero, the true subject matter, the center of the Iliad is force.” In Fagles, Homer’s poem at last met a translator forceful enough to turn that fearsome true hero loose upon an unsuspecting–and unsuspected by the publishing industry–readership. If you don’t believe me, invest a few minutes at your earliest convenience in an encounter with the Fagles version of Achilles manslaughtering his way toward the gates of Troy, Hector, and destiny. Divorce the words “death star” from their Lucasfilm associations, and you have the vengeful son of Peleus: something brilliantly baleful that should be visible only as an inhuman gleam, far off in the heavens, now brought cataclysmically to earth and destroying everything in its path (I can think of no finer compliment to pay Robert E. Howard than that in a sort of dark miracle, he briefly achieved a similar murderous paroxysm in the paragraphs where Turlogh goes berserk after the death of Moira in “The Dark Man”).

I was privileged to be able to ask Fagles a question once, about the continuity between the Iliadic Achilles and the man we meet again in The Odyssey‘s underworld sequence, when he did a reading at the Union Square Barnes & Noble in Manhattan. Much luckier were those few freshmen at Princeton who wangled their way into a seminar he taught for years and years: an immersion in the Homeric epics, with their translator and revivifier as diving instructor! Fagles’ only rival as a contemporary master of The Matter of Troy is the great Christopher Logue, who in War Music, Kings, The Husbands, All Day Permanent Red, and now Cold Calls has retold many books of The Iliad with daring, dangerous anachronisms that annihilate the distance between us and Homer; although Fagles never went that far, he once admitted that he was constantly “on the prowl for modern voices of the heroic,” and singled out Ken Burns’ The Civil War for drawing on the full resources of 19th-century American speech and rhetoric (the Burns documentary, of course, made Shelby Foote a star, and Foote’s Civil War tripledecker has been described, justifiably, as “the American Iliad“). Robert Frost here, Eliot there, Yeats here, there, and everywhere–the best poets are the most welcome of ghostly guests at Fagles’ Homeric banquets.

While at the 2006 World Fantasy Convention, the publisher/editor of The Cimmerian and I were equally jazzed by two imminent releases: Kull: Exile of Atlantis and the Fagles Aeneid. How thrilling it must have been, for a man who’d labored long on the seesaw battles wherein Hector and Achilles, Paris and Ajax are still alive, finally to get to chronicle, thanks to Virgil, the toppling of the topless towers, that archetypal apocalypse from which the stench of burning flesh and the screams of the women and children still reach us. Among the prodigies Fagles performed was to bring Turnus, often dismissed as a Hector knockoff, an ersatz Homeric antagonist, to powerful life and poignant death. And his comment that “In Virgil as in Homer, you find great reservoirs of memory,” affords a clue as to why his translations are no core curriculum chore but as affecting as The Lord of the Rings or “The Shadow Kingdom.”

I should really mention his Oresteia (1975) and versions of the Three Theban Plays by Sophocles (1982); when his Antigone speaks, every word is like the pierce-the-heart blow Uma Thurman’s Bride holds in reserve for David Carradine’s Bill. But nothing I could say would come near doing justice to either Fagles’ work, or for that matter the coruscating introductions Bernard Knox contributed to the three epics, nigh-ultimate triumphs in their own right. So instead:

Vale, to an imperator of translation.

LEO ADDS: His were the words and poetry of a vanished age — like Robert E. Howard he possessed that rare gift for communing with spirits and bringing their long-lost ways and dreams to life for modern readers:

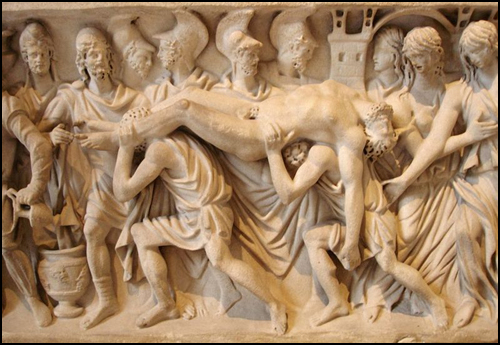

But when the tenth Dawn brought light to the mortal world

they carried gallant Hector forth, streaming tears,

and they placed his corpse aloft the pyre’s crest,

flung a torch and set it aflame.At last,

when young Dawn with her rose-red fingers shone once more,

the people massed around illustrious Hector’s pyre. . .

And once they’d gathered, crowding the meeting grounds,

they first put out the fires with glistening wine,

wherever the flames still burned in all their fury.

Then they collected the white bones of Hector —

all his brothers, his friends-in-arms, mourning,

and warm tears came streaming down their cheeks.

They places the bones they found in a golden chest,

shrouding them round and round in soft purple cloths.

They quickly lowered the chest in a deep, hollow grave

and over it piled a cope of huge stones closely set,

then hastily heaped a barrow, posted lookouts all around

for fear the Achaean combat troops would launch their attack

before the time agreed. And once they’d heaped the mound

they turned back home to Troy, and gathering once again

they shared a splendid funeral feast in Hector’s honor,

held in the house of Priam, king by will of Zeus.And so the Trojans buried Hector breaker of horses.