Sewer Charons, Scarab Beetles, and Salieri-ism

Sunday, March 8, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Dickens was meant by Heaven to be the great melodramatist; so that even his literary end was melodramatic. Something more seems hinted at in the cutting short of Edwin Drood by Dickens than the mere cutting short of a good novel by a great man. It seems rather like the last taunt of some elf, leaving the world, that it should be this story which is not ended, this story which is only a story. The only one of Dickens’ novels which he did not finish was the only one that really needed finishing…

Dickens dies in the act of telling, not his tenth novel, but his first news of murder. He drops down dead as he is in the act of denouncing the assassin. It is permitted to Dickens, in short, to come to a literary end as strange as his literary beginning.G. K. Chesterton, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens

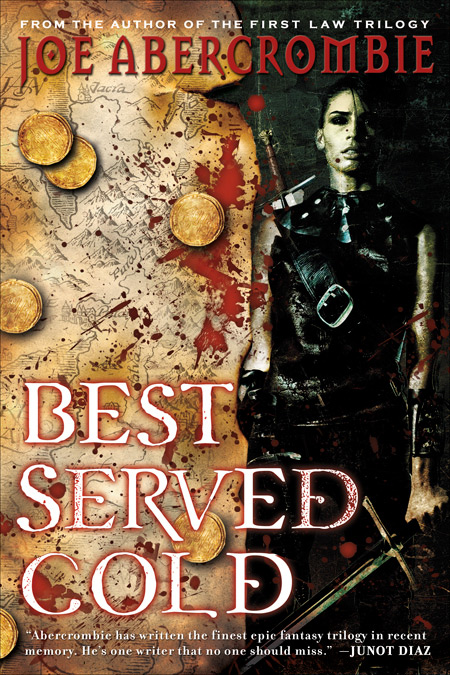

Darting come-hither glances at potential posthumous collaborators since Charles Dickens’ death in 1870, The Mystery of Edwin Drood has been completed more often than Form 1040-EZ. Dan Simmons‘ new novel isn’t just another attempt at closure and conclusiveness. Instead, Drood — the heftiness of which, as with The Terror (2007) before it, would better suit a tome intended for the bookstores of Brobdingnag than a burden to be borne by puny, hernia-prone hominids like us — plays with Chesterton’s already playful suggestions of a “melodramatic” or “strange” literary end for Dickens, of an interrupted assassin-denunciation, of the “something more” seemingly “hinted at in the cutting short of a good novel.”

Sometimes I think Harlan Ellison’s last major contribution to the fantastique, the purple-and-gold or black-and-red genres, was his part in the “discovery” of Dan Simmons. The Song of Kali (1985) so lastingly traumatized some of us that while watching Slumdog Millionaire we had to calm ourselves with reminders that Mumbai is a reassuring 1,677 kilometers away from Calcutta. Ever since that first novel, Simmons has succeeded at almost everything he has sought to do – and he has sought to do things undreamed of by even the most imaginative horror, science fiction, and dark fantasy specialists.