Mystic Chords of Memory and the Melancholy Tune Thereof

Saturday, February 7, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Mary Emmaline Reed is sharing her childhood memories of Alabama around 1865 with her granddaughter’s new swain, specifically the depredations of the locust-outdoing “riff-raff” that showed up soon after the Union Army:

Bob lunged forward in his chair. He’d hung on every word, and now he reacted physically. It is one thing to read history, but it’s altogether different to talk with someone who remembered. “And there was nothing you could do about it?” His voice was venomous against the injustice.

“Well,” Mammy mused, “yes and no. There was a little bit of help.”

“Help?” Bob picked up the word quickly. And though I’d heard the story many times, tonight, it was new again. Bob’s interest, his emotion, his deepest attention to Mammy while she talked, made me participate in the story.

“There was a man we called the ‘safety man,'” Mammy said slowly. “The people were starving, and Mr. Lincoln and the government sent in ‘safe men’ to help you. When the safety man came, the riff-raff ran off. When they came in to harass and bother you, somebody had to go get the safety man.”

Bob’s eyes were intent on Mammy’s face, and his voice was soft. “This is the first I heard of the safety man.”

“Safety men traveled around the country. Sometimes they were there when you needed them, but most of the time they stayed in town,” Mammy went on. “We tried to keep a horse and a cow or two hidden down in the woods, or the hills., but the riff-raff or the soldiers nearly always found them. If they found your horse before you could get away, then a man or boy had to run all the way to town to get the safety man. We lived several miles from town. It took time. Then, too, the safety man might not be there because someone else had got him first.”

“What could the safety man do?” Bob wanted to know.

“If he got there before the riff-raff left, he could make them put the things back and leave you alone. Sometimes, if they were already gone, he followed them to get your things back, but he couldn’t always get all of it. Still, if it hadn’t been for the safety man, things would have been much worse.”

“You said ‘Mr. Lincoln and the government,'” Bob said. “I suppose you hated Lincoln?”

Mammy shook her head. “No. Not in my family. He was on the other side, but we thought he was a good man and that he helped all he could. There’s not much anybody can do with the riff-raff that follows an army.”

Bob shook his head violently, as if to clear his mind of a horrible experience. “I guess I can see how you’d feel — even about Lincoln.”

Whereupon he rises “awkwardly,” shrugs as if to give his discombobulation the slip, and seeks shelter in humor. Among the gifts Novalyne Price Ellis gave us in One Who Walked Alone — some of which are routinely overlooked by prosecutorial REH fans eager to identify fingerprints other than Howard’s on the smoking gun — is this priceless, and all but Price-less, conversation and the vignette in which it’s embedded. So much of our reason for blogging is captured here: the way he participated in, personalized history, like parched ground gulping down rainwater; the concomitant respect-bordering-on-reverence for the aged (from a man for whom the middle age that was only just approaching seems to have been the emotive equivalent of anyone else’s old age); the skepticism about non-forceful measures implicit in the question “What could the safety man do?”; and of course the readiness to hate that served him the way the Scissorhands did Edward. It’s a shame the word hater has been so randomized and slangified in our current popular culture, because Howard was a world-class hater, so it’s arresting and amusing to witness him running up against someone who lived the history about which he is predisposed to seethe, someone disinclined to hate, inclined to credit “the other side” with compassion. By recording this one scene Mrs. Ellis created a more generous and genuine memorial to her grandmother than any mausoleum or tombstone-statuary.

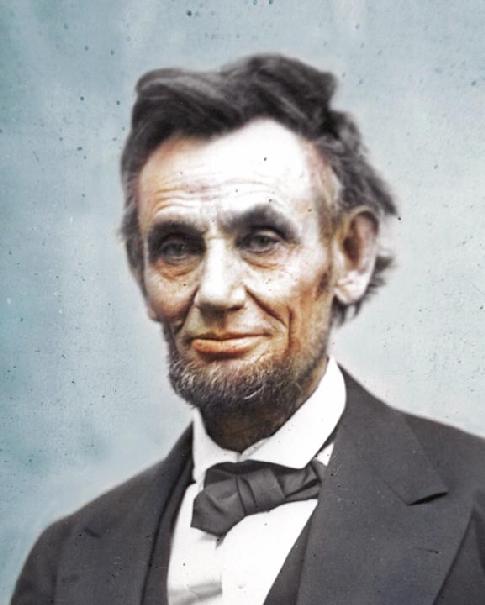

The courtesy of Mary Emmaline Reed’s “Mr. Lincoln” and the fairness of her “good man” verdict have been on my mind lately, what with the 200th birthday of our first president from Illinois coming up on February 12. And this morning’s New York Times included an article about the reopening of Ford’s Theater:

Barely 12 feet above the stage’s floor is the balustrade on which Lincoln collapsed after John Wilkes Booth shot a bullet from a .44-caliber Deringer into the back of his skull. The presidential box is draped with flags, as it was on that Good Friday evening, April 14, 1865. Hanging at the center of the balcony’s front wall, displayed for actors and audience, is the same framed portrait of Washington above which Lincoln sat.

Later, when I am led into the box itself, the theater’s director, Paul R. Tetreault, points out that the picture’s frame is nicked on its upper left side — a mark left by Booth’s spur as he leapt down onto the stage. And in the narrow arena of the box, it all becomes plausible. The comic play “Our American Cousin” would have been droning on below as Booth, who had sneaked in, silently pulled the red carpet aside to find the pine bar from a music stand he had secreted there earlier; he used it to jam the door shut.

Lincoln, 56, sat in an upholstered rocker (a reproduction: the original is in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich.); his wife, Mary, on a low, caned-bottom chair. A little farther in is the original couch on which Maj. Henry Rathbone and his fiancée sat before he attacked the intruder after Lincoln was shot, deflecting the sweep of Booth’s knife blade with his arm, which was slashed, gushing blood over everything.

It would be jejune to note that Mrs. Reed was a better person than Booth, or those who cling to Sic semper tyrannus diehardism even today. I myself haven’t been to Ford’s since high school, but remember the theater as one of those sites where Events-with-a-capital-E crowd in closer than comfort-zone maintenance would countenance. Given the chance to visit, would Robert E. Howard have sensed the ghostly presence of a tyrannicide, or merely that of a hate-blinded back-shooter?

(Students of the Cold War or the Kennedy Administration might recall an exchange once the Cuban Missile Crisis had been brought to what almost everyone save outliers way over on the left or the right would agree was a successful resolution: “Maybe this is the week I should go to the theater,” JFK joked. To which his brother the Attorney General replied, “If you go, I want to go with you.” Doubly wince-worthy to read at any time after 1968)