Clark Ashton Smith’s The Maze of the Enchanter from Night Shade Books

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

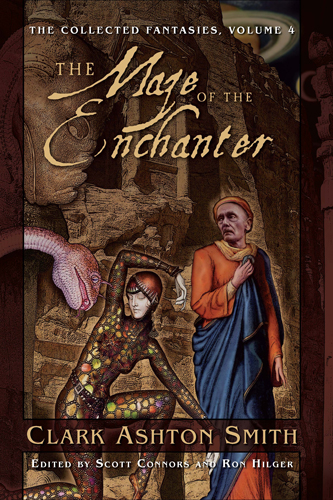

I recently received my copy of The Maze of the Enchanter: Volume Four of the Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith. Edited by Scott Connors and Ron Hilger and published by Night Shade Books, this is a sumptuous volume. Filled with sardonic, mystic and grotesque delights, The Maze of the Enchanter is a feast even for the well-read CAS aficionado. Held within its finely-bound pages are tales restored (wherever possible) to the form in which Smith envisioned them before he was prevailed upon to make emendations due to editorial fiat.

Night Shade’s “Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith” series is ambitious, seeking to put every completed tale penned by CAS between quality covers, with the ordering dictated by date of composition. Volume Four encompasses the period from May of 1932 through March of 1933. There are many, including myself, who see this period as one of Clark Ashton Smith at his height, when his imagination, enthusiasm and word-craft were at full strength.

The jacket art for The Maze of the Enchanter, as with all others in the series, has been rendered by Jason Van Hollander. Once again, Van Hollander utilized photo reference to work in examples of of Smith’s own primitive and surrealistic art, as well as a likeness of the Enchanter of Auburn himself (in this case, standing in for Maal Dweb). I’d like to think that Klarkash-Ton would be pleased.