Clark Ashton Smith’s The Maze of the Enchanter from Night Shade Books

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

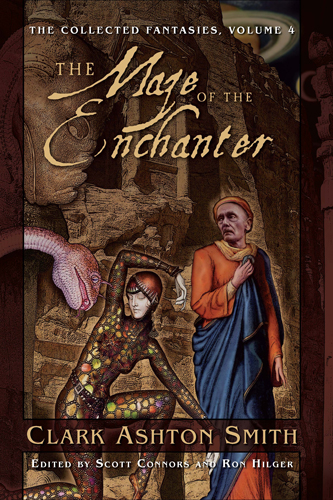

I recently received my copy of The Maze of the Enchanter: Volume Four of the Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith. Edited by Scott Connors and Ron Hilger and published by Night Shade Books, this is a sumptuous volume. Filled with sardonic, mystic and grotesque delights, The Maze of the Enchanter is a feast even for the well-read CAS aficionado. Held within its finely-bound pages are tales restored (wherever possible) to the form in which Smith envisioned them before he was prevailed upon to make emendations due to editorial fiat.

Night Shade’s “Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith” series is ambitious, seeking to put every completed tale penned by CAS between quality covers, with the ordering dictated by date of composition. Volume Four encompasses the period from May of 1932 through March of 1933. There are many, including myself, who see this period as one of Clark Ashton Smith at his height, when his imagination, enthusiasm and word-craft were at full strength.

The jacket art for The Maze of the Enchanter, as with all others in the series, has been rendered by Jason Van Hollander. Once again, Van Hollander utilized photo reference to work in examples of of Smith’s own primitive and surrealistic art, as well as a likeness of the Enchanter of Auburn himself (in this case, standing in for Maal Dweb). I’d like to think that Klarkash-Ton would be pleased.

The collection leads off with “The Mandrakes,” a tale set amidst Smith’s invented medieval province of Averoigne. Though proficient and entertaining (as are nearly all of CAS’ tales), the story does not stand out.

The same cannot be said for “The Beast of Averoigne.” The tale is both poignant and horrific. Editors Hilger and Connors have restored over a thousand words of text that CAS removed at the behest of Weird Tales’ editor, Farnsworth Wright. Having read three different versions of the story, I feel this is the best.

“The Star-Change” is an ambitious science-fiction tale, one which Smith had high hopes for. However, even his mastery of the language fails to quite do the concept justice. Entertaining, but ultimately, a noble failure.

“The Disinterment of Venus,” which Smith described to August Derleth as “a rather wicked story,” features elements both risque and ghastly, a combination that CAS used in several other tales.

Klarkash-Ton returned to his lost arctic continent of Hyperborea in “The White Sybil.” One of his most-reprinted tales, “The White Sybil” is nearly a prose poem, a literary form of which CAS is the (almost) undisputed master. Besides the haunting beauty of the story itself, I am intrigued by the  parallels betwixt “The White Sybil” and Robert E. Howard’s “The Frost Giant’s Daughter.” Both tales involve the pursuit of a mysterious female of ethereal and icy beauty, which pursuit ends with the protagonist nearly dead in the icy wastes, with only a mysterious memento as proof of his adventure. Of course, there are stark (and fairly predictable) differences. Smith’s protagonist is a poet, while Howard’s hero is a red-handed barbarian. Still, the congruences are almost eerie when one considers that Smith wrote his tale just a few months after Howard and there is no chance whatsoever that CAS could have known of “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter.”

parallels betwixt “The White Sybil” and Robert E. Howard’s “The Frost Giant’s Daughter.” Both tales involve the pursuit of a mysterious female of ethereal and icy beauty, which pursuit ends with the protagonist nearly dead in the icy wastes, with only a mysterious memento as proof of his adventure. Of course, there are stark (and fairly predictable) differences. Smith’s protagonist is a poet, while Howard’s hero is a red-handed barbarian. Still, the congruences are almost eerie when one considers that Smith wrote his tale just a few months after Howard and there is no chance whatsoever that CAS could have known of “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter.”

Hyperborea is also the setting of “The Ice-Demon.” This tale is one that I hold up as an example of Smith’s pioneering work in the sub-genre of sword-and-sorcery (though it is not to be compared to “The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles” nor “The Black Abbott of Puthuum”). Quangah, a barbarian huntsman, guides two venal merchants in their quest for a treasure lost to the eponymous entity of the tale. Once again, we see some temporal and thematic coincidence between CAS and REH. The protagonist of Howard’s “The Cairn on the Headland” (written a few months after “The Ice-Demon”) is forced to lead a greedy academic to the grave of Odin, who is then revealed in all his boreal, Lovecraftian glory. Something cold, eldritch and vaguely Odinic must have been in the air in the second half of 1932, since August Derleth wrote his first Ithaqua tale at almost the exact same time.

Smith returned to what was probably his favorite venue with “The Isle of Torturers,” which takes place in Zothique, the last continent of a dying Earth. Sardonic and ironic, it hearkens back to one of CAS’ primary influences, Edgar Allan Poe.

David Lasser, the editor for Wonder Stories, suggested the plot of “The Dimension of Chance” to Smith. Like “The Star-Change,” the concept is one that would be difficult for any author to pull off.

“The Dweller in the Gulf” is set upon Smith’s conception of a future Mars, one with sentient inhabitants, that is being slowly colonized by humans from Earth. Smith called the story “monstrous and cruel.” It is definitely that. The tale is also a gem of science-fictional horror.

Clark Ashton Smith introduced his ultraterrene sorceror, Maal Dweb, with “The Maze of the Enchanter.” The story is set upon the world of Xiccarph, which circles a trinary star-system. This tale, as well as its sequel, “The Flower-Women,” would seem to have been an influence upon Jack Vance.

William Beckford’s Vathek was one of Klarkash-Ton’s primary literary influences. When H.P. Lovecraft suggested to Smith that he should complete the third and unfinished tale in Beckford’s The Episodes of Vathek, the Enchanter of Auburn jumped at the chance. In my opinion, Smith’s “posthumous collaboration” with Beckford on “The Third Episode of Vathek” is one of the most successful examples of its kind.

Amongst the “Dark Trinity” of Howard, Lovecraft and Smith, the fiction of CAS has always been the hardest to come by. After several years of yearning  to read his tales, I managed to find The Last Incantation (edited by Donald Sidney-Fryer) at a nearby K-Mart when I was about sixteen. “Genius Loci” was the last story therein, and it is the twelfth in The Maze of the Enchanter. I have read “Genius Loci” many, many times and have recommended it to numerous friends. Not one of them has ever regretted the reading of it (to my knowledge). A masterful tale of quiet, supernatural horror.

to read his tales, I managed to find The Last Incantation (edited by Donald Sidney-Fryer) at a nearby K-Mart when I was about sixteen. “Genius Loci” was the last story therein, and it is the twelfth in The Maze of the Enchanter. I have read “Genius Loci” many, many times and have recommended it to numerous friends. Not one of them has ever regretted the reading of it (to my knowledge). A masterful tale of quiet, supernatural horror.

“The Secret of the Cairn” was probably the heretofore-undiscovered gem in this collection for me. I have read almost all of CAS’ tales, but somehow this one had slipped by until now.

Klarkash-Ton made another foray into the realm of sword-and-sorcery with “The Charnel God.” Robert E. Howard commented to Smith that, “I don’t know when I’ve read anything I admired more.” ‘Nuff said.

Smith followed up that Zothiquean tale with another masterwork: “The Dark Eidolon.” Therein, CAS spins a yarn of hubris, hate and sorcerous vengeance. We can only imagine the additional dark delights the unedited story would have provided, since the original seems lost.

“The Voyage of King Euvoran” is a story also set in Zothique (though originally intended for a Hyperborean clime). While picaresque, droll and all-around entertaining, I don’t find it one of Smith’s best tales (even though it provides data that the fantasy cartographer in me appreciates).

Returning to his future Mars, Smith penned “Vulthoom.” While good, I don’t think it holds up against “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis” or “The Dweller in the Gulf.”

“The Weaver in the Vaults” is another excellent tale set in Zothique. It once again proves that if someone goes underground in a Clark Ashton Smith story, that someone probably won’t come back alive.

The appendices for this volume (as in all volumes previous) are provided by the crack team of Connors and Hilger. As always, their commentaries are concise and informative. The editors and Night Shade have a lot to be proud of with this book and I can’t wait for the fifth and final installment.