Something to Do with Deathlessness, Part Three: Splintered Shards of Time’s Reflection

Friday, September 12, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Part Two: Eyes We Dare Not Meet in Dreams

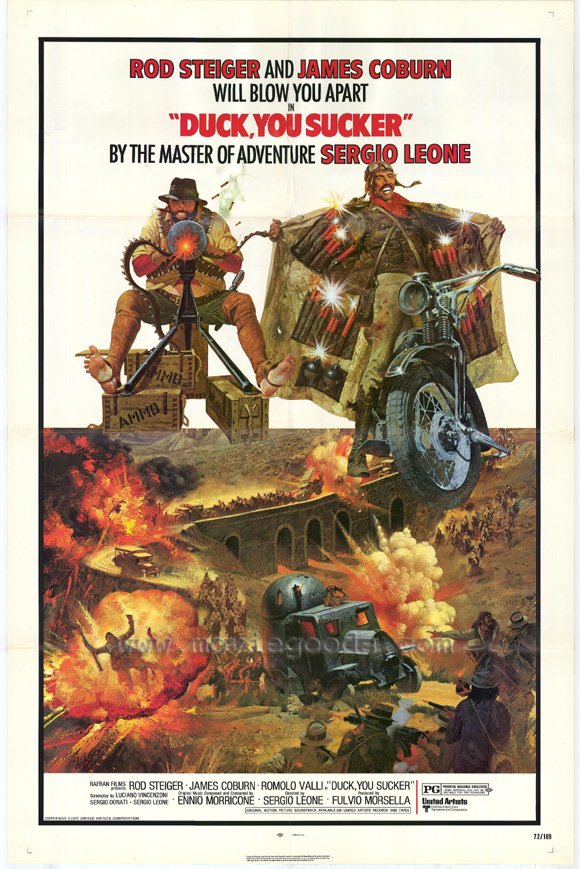

Sergio Leone’s 1972 film Duck, You Sucker was released as Once Upon a Time, the Revolution in France. Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, like Leone’s Sean Mallory, is a revolutionary, the very first revolutionary, and might nod understandingly at Mallory’s confession that “When I started using dynamite I believed in many things, all of it. . .Now I only believe in dynamite,” but Once Upon a Time, the Revolution works better as an alternate title for the 1979 Conan novel The Road of Kings than for any Kane story. Wagner wrote two Howard pastiches that redeemed the very concept of a Howard pastiche, and if The Road of Kings does not quite measure up to Legion from the Shadows it is in no small part because it is not the novel he had in mind. Just as Duck, You Sucker was a movie that Leone planned only to produce — in his head and heart he was already hard at work on Once Upon a Time in America — until the prospect of a walkout by Rod Steiger and James Coburn forced him back into the director’s chair, The Road of Kings is a fallback option, a salvage job necessitated by L. Sprague de Camp’s veto of Wagner’s original idea. The usurpation epic Day of the Lion was smothered in its cradle to make room for de Camp and Carter’s War-of-the-Roses-with-plastic-petals Conan the Liberator.

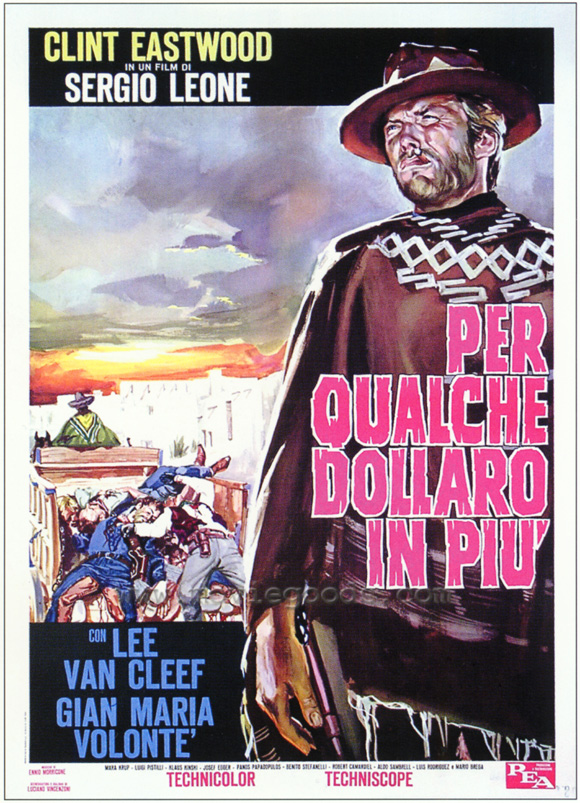

Duck, You Sucker was conceived as a riposte to spaghetti Westerns like Damiano Damiani’s A Bullet for the General or Sergio Corbucci’s A Professional Gun and Vamos a matar, compañeros, all of which involve uneasy alliances between cynical gringo or northern European mercenaries and initially apolitical campesinos who down tools and take up arms in response to injustice. Mallory, Leone’s northern European, is an explosives effort but also a full-time revolutionary, an IRA man with a British price on his head, while Juan Miranda is a bombastic bandit who is duped into a new role as “a great, grand and glorious hero of the revolution.” Wagner’s Northern mercenary is none other than Conan, ideologically naïve — his co-conspirators tease him about there being no word for “republic” in Cimmerian — but not a naïf. As a title, Day of the Lion was intended to evoke The Hour of the Dragon, and Wagner, than whom Howard has had no more alert and attentive reader, clearly picked up on the extent to which Zingara in the REH novel is not post-reconquista Spain but rather the anarchic Mexico of the same period covered by Duck, You Sucker.