Fans of Sword-and-Sorcery have cause to rejoice at the impending release of The Children of Húrin by J.R.R. Tolkien, an author I hold in unparalleled esteem for reasons largely beyond my ability to explain.

Tolkien was my first and my best, the man who set me atop a sorcerous, literary Lonely Mountain from which I have blissfully viewed the world ever since. He taught me that history was magical, and that myth was but truth under another name. To this day I marvel at the fell majesty and cadence inherent in even his most mundane passages, how every word chimes like notes from a perfectly tuned instrument. He was a master at enclosing whole worlds within outwardly innocuous words — in The Road to Middle Earth and J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, two of the most revelatory volumes written about Tolkien, philologist Tom Shippey demonstrates to devastating effect how precise the author was in choosing words with fascinating etymologies that point like bony fingers towards long forgotten historical deeps. As a fantasist’s fantasist, his legendarium contains seemingly endless layers of rich literary sediment and mythological substrata, with ages of fallen cities and relics and histories and theology waiting — sometimes for decades — to be unearthed by a perceptive reader. More than any other author I’ve read, his work defies attempts to subjugate it, to feel as if you have gathered its full measure and discovered all its secrets. The scope of the various tales he wrote of Arda and Middle Earth can only be compared to the near infinite and daunting immensity of real history — perhaps because so much of Tolkien’s work is tied not to fantasy but to reality, with deftly utilized words chosen for deep-seated philological reasons that resonate often unconsciously in our minds, each of them Wonderstrands as intricate as they are beautiful.

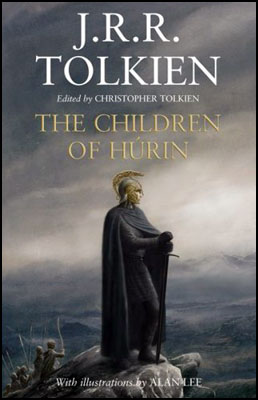

You see, I told you I couldn’t explain it. Suffice it to say that Tolkien reached literary heights that most fantasy authors haven’t even dreamed of, much less accomplished. Oftentimes the “high fantasy” genre that has sprung up at the feet of his achievement feels so desiccated precisely because he set the bar so unfathomably high. Knowing this, it is no small matter that The Children of Húrin is on its way to bookstores this April 17, for the tale housed within constitutes the Englishman’s most bloody, war-torn, and tragic story, one that virtually demands comparison to Howard’s gloomy dreamscapes in the sister realm of Sword-and-Sorcery.

Most of what we’ll read in The Children of Húrin has been published before, either in The Silmarillion or in sundry volumes of The History of Middle Earth. The difference here is that for the first time all of these disparate gems are now to be united into a towering, 320-page masterpiece that threatens to bring the pathos of the story home with a forcefulness not seen since The Lord of the Rings thundered onto the scene fifty years ago. The tale contains some of the very best things Tolkien ever wrote, passages that (to use an analogy oft employed by fellow blogger Steve Tompkins) perform open-heart surgery on the reader, scenes that I cherish above all others in literature. My gut tells me Howard would have valued them, too. Listen:

Then all the hosts of Angband swarmed against them, and they bridged the stream with their dead, and encircled the remnant of Hithlum as a gathering tide about a rock. There as the sun westered on the sixth day, and the shadow of Ered Wethrin grew dark, Huor fell pierced with a venomed arrow in his eye, and all the valiant Men of Hador were slain about him in a heap; and the Orcs hewed their heads and piled them as a mound of gold in the sunset.

Last of all Húrin stood alone. Then he cast aside his shield, and wielded an axe two-handed; and it is sung that the axe smoked in the black blood of the troll-guard of Gothmog until it withered, and each time that he slew Húrin cried: “Aure entuluva! Day shall come again!” Seventy times he uttered that cry; but they took him at last alive, by the command of Morgoth, for the Orcs grappled him with their hands, which clung to him still though he hewed off their arms; and ever their numbers were renewed, until at last he fell buried beneath them. Then Gothmog bound him and dragged him to Angband with mockery.

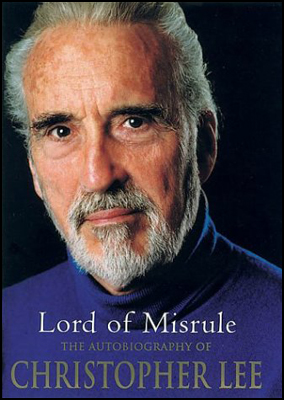

I’m hoping that this new release serves as an Athelas salve of sorts for me. The last few years have been bitter ones for this Tolkien fan, as the Peter Jackson movies methodically reforged the Englishman’s masterpiece into a often silly and irreverent roller-coaster ride for audiences addicted to a Six Flags level of momentum and excitement. The arguments I’ve heard in favor of Jackson’s vision — epic widescreen compositions worthy of Kurosawa or Leone, actors who bring a Shakespearian eloquence and grandeur to the proceedings — seem to be hopelessly offset by the reductio ad absurdum of Jackson’s painfully offensive ghettoizing of Tolkien’s meticulously constructed story. Trash-talking dialogue (“Let’s hunt some Orc, yo!”), hip-hop battle tactics (Legolas bustin’ moves on Oliphants and poppin’ caps into cave trolls and Uruk-hai) and hobbit fart jokes mix uneasily with Fabio-inspired romance to create a Frankenstein’s monster Rings that occasionally wows or moves but in the end fails utterly to convey the grand themes that were Tolkien’s life’s blood. Say what you will of John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian — even at his worst he directed the material with a refreshing seriousness, and his attempts at comedy and battle prowess grew organically out of a fundamentally grave story and characters. By the end (the sixth consecutive end, by my count) of Jackson’s Return of the King I felt insulted not only for Tolkien but on behalf of legions of dead lying forgotten under poppy-strewn fields and ancient Saxon ruins. One of the few assuagements to be had in a post-Jackson world dominated by Armani Aragorn and Aerosmith Arwen is knowing that Christopher Tolkien shares my dismay in spades, a hollow triumph to be sure, but one which helps reduce my feelings of loneliness whenever the Moviegoing Majority sings the praises of travesties like Jackson’s predacious Faramir or his puffed-up and self-important Théoden.

I’m also tired of the artistic talent dominating modern Tolkien publishing — Alan Lee doesn’t do it for me, never has. His desaturated and dreary vision too often transforms Middle Earth into a chilled morgue viewed through a pale shroud. For all of the perceived faults of the greeting card school of Tolkien illustration — Darrell K. Sweet, the Brothers Hildebrandt — at least their work overflows with color and vibrant emotion, both features of Tolkien’s prose that I delight in. In my mind’s eye Tolkien’s universe is awash in primary colors: orange torchlight and campfires, stunningly green woodlands, and skies the rich blue of lapis lazuli. Above all Lee fails the Elves, a race haunted by sadness and loss, yes, but who for all of that remain hopelessly devoted to a beauty the likes of which we might only see today in a particularly exceptional National Geographic photo essay. The pseudo-Celtic, Enya-esque conception of the elves as envisioned by Lee — ghostly hypnotic figures sleepwalking through monochromatic woods of perpetual torpor — make the Elves seem less like God’s Elder Children and more like phantoms from a 70s “be-in.”

Take a good look at the frowning, severe, and morose Lee-and-Jackson-designed Elves above, and then ponder Tolkien’s lighthearted exchange between these selfsame Elves and Bilbo Baggins in The Fellowship of the Ring, after Bilbo has recited a poem for their amusement in Rivendell:

The chanting ceased. Frodo opened his eyes and saw that Bilbo was seated on his stool in a circle of listeners, who were smiling and applauding.

“Now we had better have it again,” said an Elf.

Bilbo got up and bowed. “I am flattered, Lindir,” he said. “But it would be too tiring to repeat it all.”

“Not too tiring for you,” the Elves answered laughing. “You know you are never tired of reciting your own verses. But really we cannot answer your question at one hearing!”

“What!” cried Bilbo. “You can’t tell which parts were mine, and which were the Dúnadan’s?”

“It is not easy for us to tell the difference between two mortals,” said the Elf.

“Nonsense, Lindir,” snorted Bilbo. “If you can’t distinguish between a Man and a Hobbit, your judgement is poorer than I imagined. They’re as different as peas and apples.”

“Maybe. To sheep other sheep no doubt appear different,” laughed Lindir. “Or to shepherds. But Mortals have not been our study. We have other business.”

Imagine that: Elves laughing and joking and smiling and applauding! The above scene, along with so much else in Tolkien’s original epic, remains inconceivable in Jackson and Lee’s stylized, reductive renderings of Middle Earth. The cover to The Children of Húrin, revealed just this morning, is one of Lee’s less objectionable efforts, but I’m dreading the moment when I have to view the interior plates, and hope that there will eventually be an illustration-free hardcover edition. I yearn for something different: set Darrell K. Sweet’s often artificial fantasy work aside for a moment, and take a gander at his outstanding western paintings — that’s the full spectrum and sweeping majesty that Middle Earth demands. Or consider another artist likely to elicit groans from the Frazetta-lovers of Howardom: Thomas Kinkade. The self-proclaimed “Painter of Light” has seldom demonstrated a facility for painting characters or portraits, but his unsurpassed ability to tinge outwardly mundane landscapes with innate magic and immortal beauty is perhaps the closest any artist has come to hinting at what Tolkien’s Rivendell, Lórien, Vales of Anduin, or Grey Havens should look like. Such artists, their abilities properly channeled, would provide a welcome antidote to Middle Earth’s decades-long, Lee-conjured cloud cover.

I love how Amazon.com declares that Húrin is “the first complete book by J.R.R. Tolkien in three decades,” as if the redoubtable professor were still alive and hunched at his desk, methodically teasing and conjuring new stories from his invented world. Of course that’s not far from the truth, because Tolkien’s work yet seethes with passion and sorrow and tears unnumbered, attracting readers both new and old to black axes and white flames, to starlit hopes and mires of blood, to armies “ten thousand strong, with bright mail and long swords and spears like a forest.” His tales ever remind us of both our need for heroes and our penchant for hubris — of the power of evil, and the redemption of sacrifice:

By the command of Morgoth the Orcs with great labour gathered all the bodies of those who had fallen in the great battle, and all their harness and weapons, and piled them in a great mound in the midst of Anfauglith; and it was like a hill that could be seen from afar. Haudh-en-Ndengin the Elves named it, the Hill of Slain, and Haudh-en-Nirnaeth, the Hill of Tears. But grass came there and grew again long and green upon that hill, alone in all the desert that Morgoth made; and no creature of Morgoth trod thereafter upon the earth beneath which the swords of the Eldar and the Edain crumbled into rust.

April 17 can’t come soon enough.