An Occurrence, But Not at Owl Creek Bridge

Friday, May 25, 2007

posted by Steve Tompkins

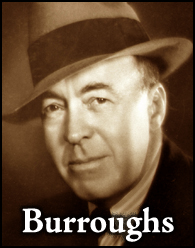

Heading into the holiday weekend and with Howard Days dominating the event horizon like a black colossus, I thought that as a capper to some recent Jack London posts I would excerpt one of my favorite literary anecdotes (my all-time favorite involves Joyce’s habit, after goading this or that belligerent drunk or intolerable pest in Parisian nightspots, of delegating to his drinking buddy, the younger, bigger, and stronger Ernest Hemingway, with the airy instruction “Deal with him, Hemingway. Deal with him”). This one features not only London and the most significant American weirdist between Poe and Lovecraft, but also George Sterling (who is likely to notch more index appearances than anyone save Clark Ashton Smith and possibly HPL in Scott Connors’ can’t-be-published-soon-enough CAS biography) and is on loan from Richard Saunders’ 1985 Ambrose Bierce: The Making of a Misanthrope. The Saunders book is not unimpeachable–“Although the poem received national attention and made other critics accept Sterling as a serious poet, ‘A Wine of Wizardry’ was far from the masterpiece Bierce had labeled it,” he snipes at the key non-Klarkashtonian poem in CAS studies –but I will always be grateful to it for the disclosure that London squired Sterling “through the exotic world of Chinese brothels on the Barbary Coast”–and for this epic encounter:

[Sterling] seized upon the opportunity of arranging a meeting between the two titans by personally inviting London (a member of the club since 1904) to attend the August 1910 High Jinks at the Bohemian Grove, which he knew Bierce would be attending.

Clearly Sterling was a great admirer of both men. but his motive for putting together the two writers, one of whom was known to be a socialist and the other known contentiously to label anyone veering from the accepted political norm as an anarchist, is still a matter of conjecture. Some biographers suggest that Sterling set up the meeting to establish once and for all which man would be his guru. Others think it was simply a mischievous prank. Regardless of his motive, in the summer of 1910 the chief players in this little drama were approaching the event quite differently.

While Bierce had spent most of the early summer leisurely canoeing on the Russian River and hiking in the woods around Guerneville, London had become despondent over the results of the July Fourth heavyweight boxing match held in Reno between the great white hope, Jim Jeffries, and the reigning title holder and first black heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson. A white supremacist, London covered the fight for the San Francisco Chronicle, and after Johnson knocked out Jeffries in the fifteenth round the paper’s headline read “Jack London Sees Tragedy in the Defeat of White Champion.” Moreover, London had lost a considerable amount of money by betting on Jeffries, and he was in such a terrible mood over it that he was ready for a fight himself, writing to Charmian in late July about his impending meeting with Bierce: “Damn Ambrose Bierce. I won’t look for trouble, but if he jumps me, I’ll go him a few at his own game. I can play act and abuse just for the pure fun of it. If we meet, and he’s introduced, I shall wait and watch for his hand to go out first. If it doesn’t, hostilities begin right there.”

When the two men finally converged under the same roof at the Bohemian Club in August a nervous George Sterling thought better of the match up. “You mustn’t meet him,” the poet pleaded with Bierce, according to his own account of the tension-filled encounter. “You’d be at each other’s throats in five minutes.”

“Nonsense,” said Bierce, already tipsy and leaning on the rustic redwood bar at the club, “bring him on. I’ll treat him like a Dutch uncle.”

As it turned out Bierce kept his word, for when a huge crowd of club members gathered around the bar to witness what they thought would be the English-language culmination of two celebrated and opposing points of view, all they saw was a tentative introduction by Sterling, an outstretched hand offered by Bierce and London’s acceptance of his open gesture of friendship. While the threat of actual physical combat was lessened by Bierce’s uncharacteristically warm greeting, most observers still stood at a safe distance. There was no need to be leery. Bierce had somehow learned that Jack and Charmian’s first child had died only a few days after birth several months earlier and had therefore decided in advance that things would be kept light. Having lost two grown children of his own, Bierce was sensitive to London’s loss, although the subject was never brought up. Instead the two men matched each other drink for drink and gradually found they had more in common than they thought. Bierce had worked for William Randolph Hearst when the man had first broken into newspaper publishing after acquiring the Examiner, and London had done some brilliant reporting for that same newspaper while covering the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Furthermore, their mutual damnation and total rejection of the artists’ colony at Carmel created an odd intellectual bond. Bierce’s comment that he would never want to be identified with Carmel because he was “warned by Hawthorne and Brook Farm” (a reference to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s brief but disappointing association with an experimental art colony in West Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1841) reflected exactly what London felt, and in fact one of London’s novels published three years later, The Valley of the Moon, was his vindication of the choice to marry Charmian and live in isolated Glen Ellen.

Politics aside, the two writers proceeded to get so blitzed that Sterling and Arnold Genthe (the famed society photographer who also managed to capture the early Carmel years, as well as everyday scenes of the pre-1906 Chinatown in San Francisco) were forced to come to their aid. According to Genthe’s autobiography As I Remember, he and Sterling were forced to remove the two men to a nearby campsite, where the four of them sat around a roaring fire drinking and philosophizing until “none of us quite knew what we were talking about.”

After several more hours of serious drinking the quartet demonstrated the degree of their inebriation by deciding to continue their alcoholic odyssey at Upshack, about two miles away. After crossing the dangerous Russian River in a rowboat the men stumbled along a set of railroad tracks that paralleled the river for a few hundred yards, then noticed Bierce had disappeared. Retracing their route while calling out his name, the three men finally spotted him at the bottom of a twenty-foot embankment. Evidently Bierce’s derby hat had fallen off his head and rolled to the water’s edge, and he had climbed down the steep slope to fetch it and decided to curl up in a soft fern bed for a short nap. When his companions woke him up he put on his derby, climbed back up the tracks and resumed the trek to his brother’s cabin as if nothing had happened. Upon reaching Upshack Sterling promptly passed out, and Bierce and London continued to drink and talk the night away like long-lost buddies, each consuming a bottle of Three Star Martel in the process.