Paging Edgar Winter

Wednesday, March 14, 2007

posted by Leo Grin

Print This Post

Print This Post

Camille Paglia, one of my favorite cultural commentators — I gracefully set aside our political disagreements — remarked in a recent column upon an exciting new book of literary criticism due to be released on May 1:

I read a fabulous book last week — John Lauritsen’s The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein, which will be published in May by the gay-themed Pagan Press, based in Dorchester, Mass. Lauritsen, who is known for his work in gay history and for his heterodox views of the AIDS epidemic, sent me an advance copy, which arrived as I was on my way to midterm exams. Its thesis is that the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and not his wife, the feminist idol, Mary Shelley, wrote Frankenstein and that the hidden theme of that book is male love.

As I sat there reading while proctoring exams, I tried unsuccessfully to stifle my chortles and guffaws of admiring laughter — which were definitely distracting the students in the first rows. Lauritsen’s book is important not only for its audacious theme but for the devastating portrait it draws of the insularity and turgidity of the current academy. As an independent scholar, Lauritsen is beholden to no one. As a consequence, he can fight openly with myopic professors and, without fear of retribution, condemn them for their inability to read and reason.

This book, which is a hybrid of mystery story, polemic and paean to poetic beauty, shows just how boring literary criticism has become over the past 40 years. I haven’t been this exhilarated by a book about literature since I devoured Leslie Fiedler’s iconoclastic essays in college back in the 1960s. All that crappy poststructuralism that poured out of universities for so long pretended to challenge power but was itself just the time-serving piety of a status-conscious new establishment. Lauritsen’s book shows what true sedition and transgression are all about.

Lauritsen assembles an overwhelming case that Mary Shelley, as a badly educated teenager, could not possibly have written the soaring prose of Frankenstein (which has her husband’s intensity of tone and headlong cadences all over it) and that the so-called manuscript in her hand is simply one example of the clerical work she did for many writers as a copyist. I was stunned to learn about the destruction of records undertaken by Mary for years after Percy’s death in 1822 in a boating accident in Italy. Crucial pages covering the weeks when “Frankenstein” was composed were ripped out of a journal. And Percy Shelley’s identity as the author seems to have been known in British literary circles, as illustrated by a Knights Quarterly review published in 1824 that Lauritsen reprints in the appendix.

The stupidity and invested self-interest of prominent literary scholars are lavishly on display here in exchanges reproduced from a Romanticism listserv or in dueling letters to the editor, which Lauritsen forcefully contradicts in acerbic footnotes. This is a funny, wonderful, revelatory book that I hope will inspire ambitious graduate students and young faculty to strike blows for truth in our mired profession, paralyzed by convention and fear.

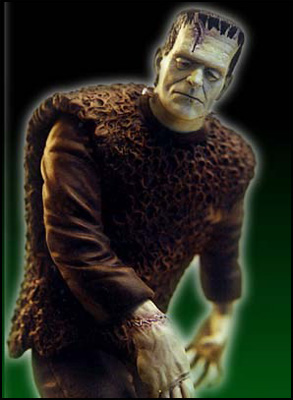

One assumes that this book will either be roundly ignored or savaged by readers, scholars, and academics of all stripes. But just imagine if this book isn’t some crackpot theory, and if considered scrutiny or future textual and stylometric examination proves it to be all-too-true. What a bombshell — think of all the books out there that would be wrong, all of the films and fiction that would be, in effect, perpetuating a great lie. It makes the hurdles Howard scholars have to navigate — crazed suicide, Oedipal hack, sloppy amateur — look like pebbles in the road by comparison. Would they digitally remove Elsa Lanchester at the beginning of James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein, the way they’re currently taking out guns, cigarettes, and images of the Twin Towers? Sillier things have happened. (And how will that seismic revelation color Bysshe Shelley’s review of the novel?)

More interesting to me is her comments on how boring literary criticism has become, and the exhilaration that is the gift of the best criticism. The function of literary criticism to my mind is quite simple: illuminate the work being examined in such a way that it can never be read again without recalling the critic’s ideas, leaving the work permanently expanded in the reader’s mind. Within those parameters, anything goes. Humor, wit, audaciousness, anger — I welcome all of these things in criticism as long as the goal of expansion is obtained. Criticism need not — must not? — be boring or plodding, weighed down with footnotes and stylistic rules and lame academic posturing. And yet too many critics become so mired in self-created mazes of pet theorizing and laborious deconstruction that the work itself is not illuminated but lost entirely. Paglia’s right: when a really well-written piece of criticism comes along, it’s exhilarating, and it sends you scurrying back to the original work with eyes wide open, regenerating the old stories and giving them beachheads of modern relevance with which to carry on into the twenty-first century.

If Bysshe Shelley becomes the undisputed author of Frankenstein, what will that do to his reputation? If Howard becomes the subject of books written by exhilarating critics with talents and insights capable of expanding Howard’s modern relevance and artistic achievement, what will that do for him, and by extension for the genre of Sword-and-Sorcery? I look forward to the day we have our own stable of Camille Paglias, John Lauritsens, and Leslie Fiedlers in Howard studies, writing books that intelligently challenge and frustrate and inspire, and that force people again and again back to the original works.