Guest blogger Gary Romeo writes in to respond to some of the criticisms TC blogger [redacted] leveled at both Gary and L. Sprague de Camp in Mark’s previous post. Here’s Gary:

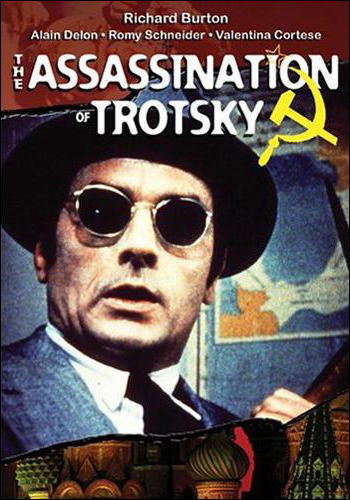

“By the 1920s, Leon Trotsky had been labeled by Stalin as an enemy of the Soviet State. He had all memory of Leon eliminated after Trotsky’s exile, turning Leon into what has subsequently been called ‘the annihilated shadow’.”

The Secret Life of Leon Trotsky — Robert Elias

“Trotsky ended up being almost like Stalin’s imaginary friend. You know, that imaginary friend some of us had as kids, the one you could blame stuff on.”

The Sheila Variations — Sheila O’Malley

The editors at Wandering Star had sought to eliminate de Camp. In their various book introductions the editors would refer to “several critics,” “schools of thought,” and “some observers.” De Camp’s name was being systemically eliminated from any Robert E. Howard discussion. Even when appropriating de Camp’s idea that Howard’s youthful stay in that Texas area known as Dark Valley became the source for Cimmeria, they refused to mention his name. Patrice Louinet later confessed: “there is absolutely no denying de Camp made the Cimmeria/Dark Valley connection before me. Not acknowledging this fact — the anteriority of the link, not the so-called borrowing — was an editorial decision on my part. De Camp […] was not gonna be in this book, period.”

But de Camp did not disappear so easily. [redacted] has resurrected him to be the person of blame for every criticism of Robert E. Howard.

The latest critic to have been tainted by the Sprague Virus, according to Mark, is Arnold Fenner. I feel compelled to do another “Nuh Uh!” to Mark’s “Waaah. Waaah.”

First off, Mark tells us the book is a mere eight stories for $100. The cost for the two Wandering Star Conan volumes was over $400, and they don’t comprise a complete set either. Mark was apparently unaware that there is a mass market hardcover available from Amazon for a mere $16.50.

Like Mark, I am bewildered by the tack that Fenner chose to take. It is obvious that Howard fans today want all praise and glory, and have no stomach for insights that are not wholly complimentary. Why Fenner wrote what he did will have to explained by Fenner, but they are not the same observations made by de Camp. Mark implies that Fenner got his information from reading The Miscast Barbarian. Lets look at it.

One issue Fenner seems to have a beef with is Howard fans, like Sprague de Camp, who try to emphasize Howard’s toughness. De Camp says in The Miscast Barbarian that “by the time Robert entered the Cross Plains High School, Howard was a large, powerful youth. When fully grown, he was 5 feet 11 inches tall and weighed around 200 pounds, most of it muscle.” Fenner writes “photographs of Robert show him as an unscarred, well-fed, and not terribly muscular young man.” If Fenner read The Miscast Barbarian he certainly disagrees with de Camp.

Fenner brings up Howard’s mention of enemies. This most likely comes from Fenner remembering the scene where Novalyne Price spots Robert’s gun while they are driving in his car as much as anything de Camp wrote.

Mark is on firmer ground when quoting Fenner about the suicide and Howard’s attachment to his mother. But there are other sources than de Camp for all this. There is Novalyne’s book and movie, as mentioned before. And de Camp was not the only one writing of Howard’s attachment to his mother and focusing on the suicide in the early 60s and 70s. Glenn Lord wrote in an introduction to the Bear Creek stories that “An excessive devotion to his mother proved to be his Achilles’ heel.” And every issue of The Howard Collector ended with the Howard death verse, “All fled, all done…”

By the end of Mark’s critique even he realizes Fenner is disagreeing with de Camp on major issues. “Howard’s use of poetical style is well documented by nearly everyone who’s written critically of the man in the past two decades (even de Camp noted it…),” says Mark in response to another Fenner criticism.

The same is true for most critics of Robert Howard. They disagree with de Camp. Let’s look at three commonly quoted critics. Sam Lundwall, Franz Rottensteiner, and Stephen King.

Lundwall’s book Science Fiction: What it’s All About quotes de Camp’s defense of Sword-and-Sorcery and his stress on the genre’s entertainment value. Lundwall states:

After having delivered this unabashed praise to escapism, de Camp goes on to note the renewed interest in Heroic Fantasy and in this respect he is undoubtedly right. Old classics are reissued by the score together with new stories of blood, thunder and well-sharpened swords. The spectrum goes from the gentle novels of James Branch Cabell to the sadistic tales of Robert E. Howard… however, looking at the state of the world — the real world — today. I can well believe there are some deeper reasons too. There was a similar interest in heroes and mighty deeds in Hitler’s Germany.

Lundwall is clearly stating that his opinion is different, by a large degree, than de Camp’s. De Camp’s view is that it is all good escapism. Lundwall is making an argument that the violent nature is not just escapism. Lundwall is saying REH is dangerous fascist-inducing stuff. So saying that this critic is influenced by de Camp is clearly wrong.

Later, Lundwall again quotes de Camp to disagree. Lundwall quotes de Camp, “[S&S provides] the reader with a heroic model with whom he for a moment can identify himself…” Lundwall’s rebuttal, “As far as entertainment goes, I can’t see anything wrong with this. Though I still dislike the over-emphasis on violence.”

So even though Lundwall later mentions the suicide, he is not doing it as a mindless drone hypnotized by de Campian propaganda. He is disagreeing with de Camp on fundamental points.

Franz Rottensteiner is another case. His The Fantasy Book quotes another de Camp defense of Sword-and-Sorcery. Rottensteiner follows the de Camp quote with a dismissive, “Apologists of this kind of entertainment trace its development back through Eric Rucker Eddison and Lord Dunsany to William Morris…. But in fact it is not even the debilitated offspring of these sagas, but rather a misbegotten child of our own technological civilization, offering a quick escape from an oppressive world.” Rottensteiner, like Lundwall, is disagreeing with de Camp to a large degree. De Camp never talked about fascist underpinnings or escaping from an “oppressive world,” just a mundane one. These guys have their own axes to grind, that are clearly different from de Camp’s views.

Stephen King is no de Campian-influenced fan of the genre either. King in Danse Macabre says “This kind of fiction, commonly called ‘sword & sorcery’ by its fans, is not fantasy at its lowest, but it still has a tacky feel….” He then goes on, “The only writer who really got away with this sort of stuff was Robert E. Howard….” Then, “Howard overcame the limitations of his puerile material by the force and fury of his writing…” Then comes the truncated Del Rey quote: “Stories such as “The People of the Black Circle” glow with the fierce and eldritch light of his frenzied intensity. At his best, Howard was the Thomas Wolfe of fantasy, and most of his Conan tales seem to almost fall over themselves in their need to get out.” But King follows that with, “Yet his other work was either unremarkable or just abysmal….”

By pointing out that de Camp is not always to blame for a critic’s negative appraisal of Howard (among other things) I have been labeled by the de Camp bashers as a decampista. It is as fine a label as any, but please don’t forget that I (and Steve Allsup) are REH fans first and foremost. I am not a fanatical de Camp fan. I like him well enough and enjoy his work but, hell, remember I forgot his birthday!

Mark makes a final plea that publishers should only hire admiring critics like Rusty Burke, himself, or others cut from the same cloth to write introductions to Robert E. Howard material. In other words, a stifling of thought, sameness, is preferred over anything that might veer from the current orthodoxy. Mark ends by basically issuing a boycott of the product. Paradox holds the Conan/Robert E. Howard franchise these days and would most likely agree on a boycott of these public-domain publications. But they should be wary of a fandom that calls for sameness and rigidity in all things related to Robert E. Howard.