[redacted] and I seem to have at least a desultory Jack London thread going, so I’d like to crack open The Star Rover for this post. The novel has long had a reputation among Howardists as James Allison’s home away from home, and Fred Blosser planted a Howard studies banner in London’s text a decade ago with “The Star Rover and the People of Night” in TDM #4, May 1997, but as the title of that article hints, Fred’s focus was Rover-ian influence on “The Children of the Night.” I’m fascinated by the novel’s Chapter XVII, which finds London, who as much as anyone other than Robert W. Service made the New World’s North his own, turning his attention to the North of the Old World and affording us an example of a major American writer contributing to “the Northern thing” decades before REH, Fletcher Pratt, Poul Anderson, or Fritz Leiber.

The nativity of the chapter’s narrator, Ragnar Lodbrog (actually an Allison-style past incarnation of Darrell Standing, who is doing the hardest possible hard time in San Quentin solitary), could not be more northern, “tempest-born on a beaked ship,” and “delivered in storm, with the spume of the cresting seas salt upon [him].” “For nursery,” Ragnar tells us, “were reeling decks and the stamp and trample of men in battle or storm.” From birth he earns the enmity of Tostig Lodbrog, alias Muspell (“The Burning”, whose immediate inclination is to drown him in “a half-pot of mead.” To establish Tostig’s badassery, London alludes to the sea-king’s having eaten “the heart of Ngun after the fight at Hasfurth” and “the spiced wine he would have from no other cup than the skull of Guthlaf.” The greatest and grimmest of Northern tales comes in with an invocation of “Gudrun’s revenge on Atl, when she gave him the hearts of his children and hers to eat while battle swept the benches, tore down the hangings raped from southern coasts, and littered the feasting board with swift corpses.” Scope that not-for-the-faint-of-heart verb “raped”; London was as bruisingly powerful aboard a longship as he was alongside a dogsled, and it’s a shame he didn’t write more things like the flashback-chapters of The Star Rover.

After proto-Howardian observations about Tostig’s entourage like “Their thoughts were ferocious; so was their eating ferocious, and their drinking,” Ragnar escapes and is finally captured by the Romans, where, from the young Robert E. Howard’s point of view, the chapter goes to hell in an imperator‘s chariot. The Northron is made “a sweep-slave in the galleys” but works his way up to “freeman, a citizen, and a soldier.” We even learn that he will eventually rise to command a legion—imagine Howard’s disgust! All of the storms and stroppiness back home are just a preamble to a Gospel According to Jack, as Pontius Pilate, who is enduring a full-court press from the Sanhedrin, Ragnar, and his highborn love interest Miriam debate what should be done with a “vagrant fisherman, this wandering preacher, this piece of driftage from Galilee.” Ragnar digs himself in deeper by insisting to Miriam “The Romans are the elder brothers of us younglings of the north. Also, I wear the harness and eat the bread of Rome.” If London’s novel did indeed “generally [go to Howard’s] head like wine,” as he told Harold Preece, Ragnar’s civis Romanum sum sentiments must have been the undrinkable lees.

(Two pop culture asides: We can’t blame London for the lamentable Revenge of the Sith-associations of the term “younglings,” and thanks to Monty Python, can anyone read or see a scene featuring Pilate or other administrators of Occupied Judaea without instantaneously thinking of Biggus Dickus? I first met B. Dickus in a German movie theater in 1981, where his nom de dubbing was Schwanzus Langus–even funnier, perhaps)

For evidence of the Ragnar chapter’s impact on Howard, we need only consult the novel-fragment published for the first time in the Del Rey version of Bran Mak Morn: The Last King, which it might still be convenient to refer to by the title Glenn Lord assigned in The Last Celt, “The Wheel Turns.” (This is the abortive project referred to in an October 5, 1923 letter to Tevis Clyde Smith–“a book which doubtless would make you tired” Howard’s narrator is Hakon, who crews for Tostig the Mighty, “a terrible warrior and a man whose wish was his only law.” Tostig’s second ship is captained by one Ragnar, and another of the dramatis personae is named Lodbrog. Where a blow from London’s Tostig sends his narrator “dazed and breathless half the length of the great board”; Howard’s Tostig is no less enraged by the narrator’s disobedience, “I caught the blow on an up-flung arm but the force was enough to knock me from my feet and send me rolling along the deck.”

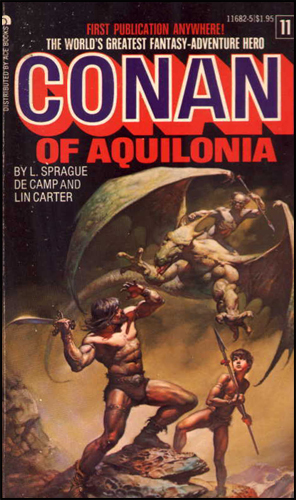

London’s Tostig feasts “under the smoky rafters of Brunanbuhr” and “Jutes” is spelled “Juts” in The Star Rover, a spelling retained by Howard, in the last sentence of whose Chapter 2, “The Viking,” two ships are “sold to the Juts at Brunanbuhr.” Howard’s fragment features an “Angle” ship helmed by Gathlaff–recall London’s reference to Guthlaf and his skull’s afterlife as a beverage holder. Interestingly, this section of “The Wheel Turns” also offers a preview of Conan’s underhanded undermining of Zaporavo in “The Pool of the Black One”:

Cunningly, without speaking against Tostig and giving him an excuse to slay me, craftily, without drawing suspicion of any sort to myself, I turned the Vikings against Tostig, against his arrogance, his over-bearing ways, his cruelty. Many of them hated Tostig anyway, so it was not such a difficult matter.

We know that when Howard was taken by a story, that story was sometimes taken by Howard, who would then make it his own. In his introduction to The Lord of Samarcand and Other Adventure Tales of the Old Orient, Patrice Louinet notes “Howard’s first attempt at writing an Oriental story was contemporary to his reading Lamb’s ‘The Wolf Chaser’ (Adventure Magazine, April 30, 1922). . .The Texan first wrote a short recap of Lamb’s story, then proceeded to write a short story, or rather outline of a story, which apparently didn’t go beyond the second page.” But I think the after-effects of London’s Ragnar chapter outlasted the rather blatant appropriation evident in “The Wheel Turns.” Might not Howard’s later “Men of the Shadows” be a sort of indignant answer-song? If barbarism is the natural state of manking, then it is damn sure the natural, the only permissible state of barbarians, and Ragnar should be ashamed of himself. Against the stark backdrop of the north of Britain, where a “high mountain wind” roars “with the voice of giants,” Howard’s unnamed Scandinavian legionary reverts to his true self as the “real” Romans are Pict-picked off one by one: “By Thor and Wotan, I would teach them how a Norseman passed! With each passing moment I became less of the cultured Roman.” We can sense Howard’s glee as his Viking remarks on “years of Roman culture [slipping] away like sea-fog before the sun” and he can’t divest himself of “all dross of education and civilization” fast enough (I feel the same way when I try to read Cicero). Picture Howard at his Underwood, glaring at his well-thumbed copy of The Star Rover as he types “I was no Roman, I was a Norseman, a hairy chested, yellow bearded barbarian. And I strode the heath as arrogantly as if I trod the deck of my own galley.”

Bran himself gets in on the de-Romanizing action: “But you are a Roman, to be sure. And yet, methinks they must grow taller Romans than I had thought. And your beard, what turned it yellow?” Is it fanciful to suggest that one reason why the first few pages of “Men of the Shadows” are a real story, rather than a rejection-earning summation of Pictish history, is because Howard was picking a fight with London/Ragnar? We need not drag in Harold Bloom’s theorizing about the anxiety of influence and the patricidal inclinations of authors just starting out to speculate along these lines.

And beyond “Men of the Shadows,” might one of Ragnar’s conversations with Miriam contain an echo-in-advance of Conan and Belît’s conversation as the Tigress glides up-river on the sinister Zarkheba? Here’s London:

Let these mad dreamers go the way of their dreaming. Deny them not what they desire, above all things, above meat and wine, above song and battle, even above love of women. Deny them not their hearts’ desires that draw them across the dark of the grave to their dreams of life beyond this world. Let them pass. But you and I abide here in all the sweet we have discovered of each other. quickly enough will come the dark, and you depart for your coasts of sun and flowers, and I for the roaring table of Valhalla.

As for other possible debts, in London we find “Once I was Ushu, the archer,” in Howard “I was Lakur the archer in the land of Kita.’ In Chapter XXI of The Star Rover, a pre-Ragnarian but equally Aryan reverie, the narrator would have us know “The sword, in battle, sings not so sweet a song as the woman sings to man merely by her laugh in the moonlight, or her love-sob in the dark, or her swaying on her way under the sun while he lies dizzy with longing in the grass.” I can’t prove it, but one of Asgrimm’s disgusted utterances in “Marchers of Valhalla” seems like a direct retort to what might have struck Howard as treacle: “The kisses and love-songs of women soon pall, but the sword sings a fresh song with each stroke.”

Returning for a moment to Before Adam, one last example of Howard redoing London to his own satisfaction possibly occurs in Chapter 1 of “The Wheel Turns,” “Back Through the Ages,” which borrows the senior writer’s term “the Younger World” and evokes “the Swift One” with a character named Swift-Foot. Red-Eye, the throwback more pongid than hominid of Before Adam, gets away with murder and worse. That surely didn’t sit well with Howard, and so we get:

For I saw red rage and there, in the swaying tree-tops, a hundred feet from the ground, we fought hand to hand, the Hairy Man and I, and bare-handed and unaided I slew him, there in tree-tops, when the world was young.

And was this cursorily described incident then one of the kernels of “Spear and Fang”? Food for thought–and in honor of London, a San Francisco treat.