Some REH recommendations

Monday, June 11, 2007

posted by Leo Grin

Print This Post

Print This Post

At this year’s Howard Days I was struck by the quality of some of the publications debuting there, and thought I’d pass on my thoughts to the Howardian public.

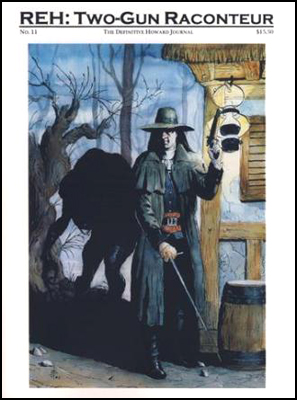

Over the last year Damon Sasser, a good friend of The Cimmerian, has actively striven to improve his flagship publication REH: Two-Gun Raconteur in a variety of ways. From soliciting more thoughtful articles to starting a blog for Howard-related news, he’s taking the best that the 1970s fanzine heyday had to offer — lots of art, rare Howard originals — and fusing it with the more scholarly, serious tone of the modern era. I note that Damon has re-christened his magazine from “The Definitive Howard Fanzine” to “The Definitive Howard Journal.” A small change, but it hints at the subtle improvements quietly executed behind the scenes.

The result of all this tinkering is a blend and accessibility that no other Howard publication can match. For those who value rare Howard stories, poems, and fragments, the latest ish contains REH’s “A Touch of Color,” published previously only in the nearly impossible-to-find chapbook Pay Day. Canadian Charles Saunders, one of fantasy’s primordial black talents, brings his vast store of knowledge on African history to bear on Howard’s Hyborian Age. Danny Street tells you everything you’d want to know about Howard’s conception of the alluring, poisonous flower known as the Lotus. Morgan Holmes reviews a new Conan comic, and Cimmerian stalwarts Leon Nielsen and [redacted] fill out the issue with even more articles. The artists include recent Cimmerian Award winner and REHupa Official Editor Bill Cavalier.

Whether you are a comic-book loving, RPG-playing fan, or an academic intent on studying Howard as a classic American writer, there is something for you in REH: Two-Gun Raconteur #11.

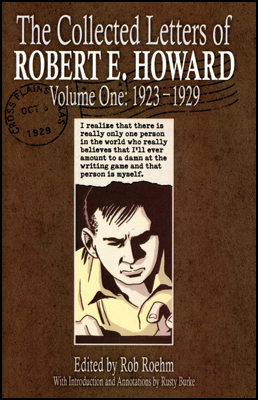

There’s been a lot of bagging on the publications put out by the Robert E. Howard Foundation of late, but it looks as if things are turning around. This latest book, which was handed out to subscribers of the series at Howard Days, suffers from none of the deficiencies of A Rhyme of Salem Town and Other Poems. Well, I still blanch at the cover — comic book imagery, no matter how skilled, subliminally infantilizes the thoughts within, whereas a sepia-toned photograph would have lent an aura of Golden Age class and distinction to those same thoughts. But the book itself is meaty, well-formatted, and filled to the brim with previously unpublished REH.

If you are the proud owner of the two-volumes of Necronomicon Press’ Selected Letters of REH, you frankly will be astounded by all of the new material on display here. The claim made by Robert M. Price in the Introduction to Volume 2 of Necro’s Selected Letters — that, unlike Lovecraft, Howard fails to reveal his true personality in his correspondence — is destroyed once and for all in a flurry of new revelations and insights into the mind of the Father of Sword-and-Sorcery. And to think that this treasure chest of riches in only the first of three set to appear this year. It’s an achievement.

My guess is that by the time this project is finished, REH’s three volumes of correspondence will have opened up as many doors to further study as Lovecraft’s five-volume series did back in the day. The publication of such a project, and the intrinsic fascination of the letters within, is a massive confirmation of Howard’s value and interest as an author worthy of, and capable of absorbing and rewarding, serious study. This is the kind of thing that tends to shake loose all kinds of scholarship that would otherwise never have been written. It’s a galvanizing force in the field, and I predict that old and new Howard fans alike will find much within these books that will spur them on to new explorations of the Texan’s fiction.

The mental picture we have of Howard is about to become much richer and more complex, exactly as Lovecraft’s did when his own letters were published. Howard’s was a serious, thoughtful, brilliant mind, and learning about how his personal life and experiences crept into (and often overwhelmed) his fiction can only improve one’s evaluation of his artistry. The snide criticisms and flippant dismissals of yesteryear keep looking sillier and sillier in the face of such books.