Frazetta & Howard, Moorcock & Howard

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

posted by Steve Tompkins

Bear with me for this first paragraph. Most people who are fascinated by Alexander the Great know that Mary Renault wrote an Alexandriad, a trilogy of novels about the conqueror’s life and the succession wars that raged after his death: Fire From Heaven (1969), The Persian Boy (1972), and Funeral Games (1981). But some might not be aware that Alexander first appeared in the final chapter of a fourth book, The Mask of Apollo (1966). Renault’s narrator, Nikeratos, a Greek actor who has watched, and narrowly escaped with his life from, Plato’s doomed attempt to bring an ideal city-state into being in Sicily, meets the young prince at the Macedonian court in Pella, and they discuss whether Achilles should have killed Agamemnon and what an alliance between the Achaeans and Trojans for the purpose of eastward expansion might have achieved. Once back in Athens, Nikeratos muses “He will wander through the world like a flame, like a lion, seeking, never finding, never knowing (for he will look always forward, never back) that while he was still a child the thing he seeks slipped from the world, worn out and spent.” What Renault is getting at is that time and chance have denied Alexander exposure to Plato’s poetry, leaving him only the far more prosaic Aristotle. The Mask of Apollo ends this way:

All tragedies deal with fated meetings; how else could there be a play? Fate deals its stroke; sorrow is purged, or turned to rejoicing; there is death, or triumph; there has been a meeting, and a change. No one will ever make a tragedy — and that is as well, for one could not bear it — whose grief is that the principals never met.

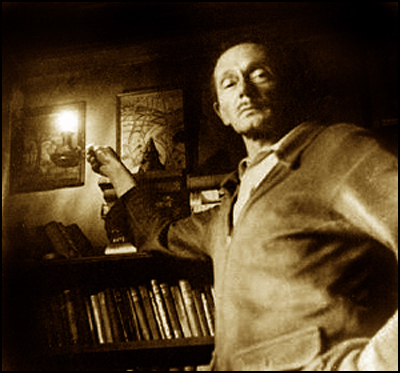

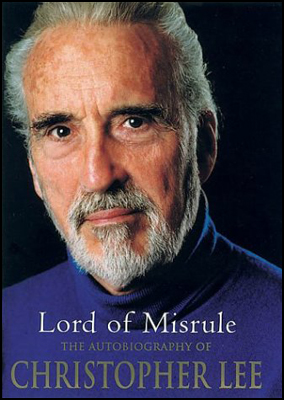

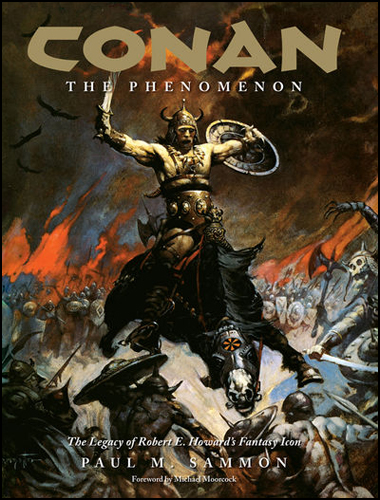

On page 57 of Paul M. Sammon’s Conan: The Phenomenon, Frank Frazetta is quoted (by way of frankfrazetta.com) as saying “I feel a certain sense of loss that Howard isn’t alive to appreciate what I’ve done with Conan.” A certain sense of loss; for me that loss is quite similar to Mary Renault’s even-more-unbearable form of tragedy in which the principals are divided by circumstance or chronology.