While browsing around the net, looking over various Howard sites and researching some other posts I am planning for you, I came across a short Howard blurb at the Fantastic Fiction website. This is a bibliographic site seemingly created by a good-hearted fan of the genre, one without an axe to grind, save the one used to break down walls between various authors of the mystifying and the macabre. Notably, the website seems to be updated regularly, given the number of as-yet-unpublished Howard books advertised on the page.

The REH blurb located there is typical for such a site, giving an all-too-short overview of Howard’s career, mentioning stories “notable for their violent energy,” tossing in a reference to the pastiches, and of course highlighting the suicide. There are numerous little quibbles to be found — Schwarzenegger is spelled wrong, and anyone calling de Camp a “pious friend” of Howard’s might want to lease out space in whatever fortified bunker Gary Romeo has bastioned himself in down Texas way. But what most captivated my attention was the theory proposed for why Howard embraced invented epochs as settings:

Some of the pulp fiction of the short-lived Texan Robert E. Howard are straightforward Westerns or historical romance; his contribution to the history of fantasy was to realize that setting his stories of ruthless hard men in Atlantis or a mythical age shortly after its fall enabled him to write without the trammels of historical accuracy.

This is written as if it is a point of pride, a notable accomplishment on Howard’s part. But too often such praise grows faint when set under the shadow of an old argument in Howard studies, the idea that Howard’s Conan stories are a mishmash and a hodgepodge of various time-periods, with some critics opining that Howard did it that way out of laziness and the need to write fast. In other words, so he could deftly avoid worrying about the “trammels of historical accuracy.”

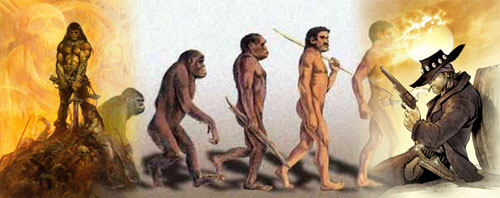

Others such as myself believe that this technique, as executed by REH, was ultimately far more mash than mish, an ingenious way for him to manipulate our expectations of historical accuracy in order to comment on history, Time, and the everlasting barbarism of man. To shock his readers with similarities not of the body — costumes, dialects, anachronisms — but of the soul. In other words, he meant to do it, planned it that way, often meticulously and by great mental and artistic exertion on his part. That in fact he took far longer to write stories containing such themes than if he had truly swore off historical accuracy.

Folks who disagree with this, who insist that Howard wrote fast and furious for the pulps with too-little regard for the substance of the tale’s milieu, are able to score a few cheap points off of various typos and word usages found in the Conan stories (swords jumping from the ground back into the scabbard, three mutually exclusive words to describe the same helmet, the key invention of stirrups appearing in Howard’s historical episodes long before they actually did in our own). But once that thin gruel is exhausted, such critics have much to answer for. Numerous articles have been written about the often uncanny historical accuracy to be found in Howard’s stories, from the usage of what was then accepted 1920’s history for the backstory of his Picts and Aryan barbarians, to the way he described guns and other implements of the Wild West, to the nuanced way Howard differentiated the trappings of armor, weapons, and battle tactics in historical tales set in the far east or in the Muslim lands of the Middle Ages. To dedicated readers of Howard, and E. Hoffmann Price’s well-known scoffing notwithstanding, it is clear that Howard invested far more time and effort into historical accuracy than he is usually given credit for. Howard even studied Gaelic and other languages as much as he could in the desolate isolation of turn-of-the-century Texas, presaging similar techniques being used at the same time by the then-Hobbitless J.R.R. Tolkien in his private thoughts and notebooks. Slipshod critics have written much about Howard’s invented names without copping to the fact that many of them — Conan, anyone? — were used with precision, expressly geared towards the evocation of historic continuity.

Many visitors to this blog have already read J. D. Charles’ exposition on “REH and Guns” for The Cimmerian (V3n1) or the two great El Borak essays written for TC by Dave Hardy (“The Great Game” in V1n2 and “Indomitable Wildness, Unquenchable Vitality” for V3n4), each of which lends credence to the idea that Howard cared much about historical accuracy. There are many more excellent essays on the subject out there — those of you wishing for a less raucous, more academically sanctioned argument can pick up a copy of the MLA indexed, peer-reviewed The Dark Man #5 for Winter 2001 and read Ed Waterman‘s “Dating ‘Wolfshead’,” which postulates (successfully to my mind) that Howard was such a stickler for historical accuracy that the unnamed time period in which the plot of the story occurs can be dated to within a few years, based on an analysis of words and archaisms that REH may well have employed with meticulous exactitude. These are only a few examples off the top of my head; there are many others.

And one only has to turn to the writings of REH fans such as Cimmerian Award-winner Dale Rippke to realize that the Hyborian Age and Kull’s Atlantis achieve their verisimilitude not only via REH’s mythic prose sparkling with “dusky, emerald witch-light,” but from Howard’s decision not to use historical allusions merely for expediency. Clearly he did his best to set his fantasy tales in a world linked to ours by race, war, thunderous migrations, and above all the hatreds and violence that have always dogged mankind, and always will. Howard was perfectly capable of writing within the trammels of historical accuracy, and to the degree that his fantasy stories — that all good fantasy stories — stray from real history, they do so in measured, thoughtful ways that serve not to free the author from history so much as bind the reader more fully to the inescapable truths of Life and Humanity.

When we finish reading “Beyond the Black River,” with its evocative conjuring of the battles for the heart and soul of the American West, who among us feels that REH used such a setting merely to be able to write westerns without worrying about accurately describing the warpaint of the Indians or the caliber of the settlers’ rifles? How silly. But get to the last lines of the tale, savor Howard’s thematic denouement, and a more audacious goal becomes clear:

“Barbarism is the natural state of mankind,” the borderer said, still staring somberly at the Cimmerian. “Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph.”

I would argue that the impact of those lines has nothing to do with fantasy per se, or with Conan, or with mere poetry or wordplay on Howard’s part. What gives them such resonance is exactly what the unnamed writer at Fantastic Fiction is criticizing: it is the fact that they are from a fantasy story that feels for all intents and purposes like a Western which gives the tale an epic sweep and timeless view of humanity that lingers long in the minds of readers. The reason so much fantasy fails and feels little more than a pastiche of Howard or Tolkien is that the writers mistake invented worlds and fantastic trappings for escape, whereas the best writers use invented realms as dreamcatchers, binding us to the tie-ribs of reality in ways otherwise impossible. A western, written with meticulous accuracy to time and place, is too often just a Western. “Beyond the Black River” is a Western too, you bet it is; but in it we find reality writ large, looming over and transcending time and place to highlight the dark, fathomless, often horrifying inner soul of mankind, replaying its grim tragedy through Age after Age.

Most interesting is how Howard’s best modern-day, “historically accurate” tales do the same thing the other way around. “The Vultures of Wahpeton,” for example, is widely considered to be Howard’s most successfully executed Western. Based on an actual historical episode, the life and death of Hendry Brown, it is one of the Howard stories being groomed for movie production by Paradox Entertainment (see the forthcoming The Cimmerian V3n7 for details). And yet in this outwardly western tale of gunfights, outlaws, and American sensibilities, let us pause and dwell for a moment on the savage incursions of near-Hyborian mysticism that intrude on the proceedings:

He hated Glanton with the merciless hate of his race, which is more enduring and relentless than the hate of an Indian or Spaniard…his creed was pagan and nakedly elemental.

The merciless hate of his race? What race would that be? The “race” of Rugged Westerner? Irish/Gael?

Ancient Cimmerian?

Howard gives us more hints, as he describes the western boomtown wherein he sets his tale of gold and gloom:

Here there were no delicate shadings or subtle contrasts. Life painted here in broad, raw colors, in bold, vivid strokes. Men who came here left behind them the delicate nuances, the cultured tranquilities of life. An empire was being built on muscle and guts and audacity, and men dreamed gigantically and wrought terrifically. No dream was too mad, no enterprise too tremendous to be accomplished.

Sound like a Western? Or one of the many “escapes” to lands of fantastic deeds and superhuman heroes that Howard is usually credited with? Is this Wahpeton, or Aquilonia?

And how does one explain the mythic, iconic Conan-ness that Howard deftly injects into the gunplay:

Middleton stared wildly about him, through the floating blue fog of smoke that veiled the room. In that fleeting instant, as he glimpsed Corcoran’s image-like face, he felt that only in such a setting as this did the Texan appear fitted. Like a somber figure of Fate he moved implacably against a background of blood and slaughter.

And again:

Middleton’s hand was a streak to his gun butt. Even in that flash he knew he was beaten — heard Corcoran’s gun roar just as he pulled trigger. He swayed back, falling, and in a blind gust of passion Corcoran emptied both guns into him as he crumpled.

For a long moment that seemed ticking into Eternity the killer stood over his victim, a somber, brooding figure that might have been carved from the iron night of the Fates.

That iron night of the Fates stretches, in Howard’s hands, from the American West all the way back to the Hyborian Age and beyond, linked together in Howard’s writings by a witch’s brew of imagery, theme, and “historical accuracy” in the truest sense. Howard’s great achievement in fantasy wasn’t to escape reality, but to confront it in a grandiose, human struggle, the epic nature of which could not be summoned with quite as much thematic power any other way.