The above photo is well-known to those of us who have read and reread Dark Valley Destiny. In that book, the caption states: “Robert E. Howard, Dr. Isaac M. Howard, Dr. and Mrs. Solomon R. Chambers, Galveston, Texas, probably 1918.” It’s a photo that has always intrigued me, mostly because of the amazing pose REH is caught in, gazing wistfully up at the sky as if daydreaming his first stories, so distracted by the tales floating around in his mind that he can’t bring himself back to reality long enough to pose properly for the photo being taken. Dr. Howard and the Chamberses do their part to make the photo interesting, too, with Isaac standing imperiously and confidently as the nexus of attention while the others almost recoil from the towering man dominating the center of the composition.

Over the years I have been in Howard fandom, I’ve often wondered what the provenance of this photo was. Dark Valley Destiny says:

Late in 1917, Dr. Howard delivered the Chamberses’ new baby, Norris, and thereafter Dr. Chambers became restless. As he had earlier discovered that the active practice of medicine kept him away from home more than he liked, so now he found his duties at the drugstore too confining. After the Armistice of November 11, 1918, he decided to move his family to Galveston, on the Gulf of Mexico, and take up truck farming.

Of course, Dark Valley Destiny also calls the newborn Norris “Robert’s schoolmate,” and then debunks one of REH’s childhood memories by saying that schoolmate Norris didn’t remember it, so Howard probably made it up. But as we just read in the DVD excerpt above: Norris was born in 1917, making him a full eleven years younger than Howard, and so couldn’t possibly have been his schoolmate. Call me wild and crazy, but it’s small wonder he didn’t remember anything about the incident Howard wrote of considering he might not have been born yet when it happened.

Until recent years Dark Valley Destiny was the first and only place this photo was published, albeit severely cropped compared to the raw version above. I suppose de Camp got this and most of his other photos from Glenn Lord, who had been patiently hunting down and securing copies of such photos for decades. The copy above is the one Glenn has in his files, with the names written across the top like that. Glenn in turn must have got a copy from Norris, or from one of the other Chamberses.

In June of 2005, Don Herron and I went to White Settlement, Texas and interviewed Norris Chambers at length (the results of which can now be read in TC V3n10, with a further tantalizing excerpt available in V3n6). During the course of that interview I learned that Norris’ sister’s name was Deoma, which immediately set off alarm bells in my mind, because the name written on the photo above also says “Deoma.” Norris’ Mother’s name was Martha. Hmmmm. (in case you haven’t noticed, there are a lot of opportunities to say “hmmmm….” in REH scholarship).

When I got home from Texas, I looked up Deoma in the Social Security Death Index, and she is listed under Deoma E. Morgan (according to this genealogical listing on Norris’ website, Lilburn Morgan was her second husband, Lonnie Triplitt was her first). That record tells us that she was born in 1899 and died in 2000 (she was 101 years old!) That would make her around nineteen at the time of the above picture. Hmmmm — come to think of it, the lady (girl?) in that picture has always looked a little young to be the wife of the then fifty-year-old Solomon Chambers (1868-1950).

It appears, then, that de Camp assumed that Deoma Chambers was Mrs. Solomon (Martha) Chambers and wrote his caption accordingly. But now twenty-three years after the fact we finally know that the woman in the picture in not Solomon’s wife but his daughter, and hence Norris’ older sister. Those of you who already own TC V3n10 knew this already, of course — one of the perks of subscribing.

During my interview of Norris in 2005, I asked him whether he had the original of this photo, in the hope that it perhaps had some writing on the back that might pinpoint the date a bit better, or provide any additional information. He said that he didn’t have it and wasn’t sure who did, but he suspected that Deoma’s only daughter Marjorie Leeton — who is 84 years old and still living in Texas, might know where it went off to, along with several other photos Norris recalls were taken with the Howards on that Galveston trip.

Well, I contacted Marjorie, and sure enough she does have the original photo, although there are no others that she is aware of. According to her, the splotches you see on the print reproduced above are there on the original, too, perhaps caused by dripping photo developer or something at the time it was made. And most importantly, on the back of the photo itself is written the names of the subjects along with the following additional information: “Feb 1918 near Alta Loma, Texas.”

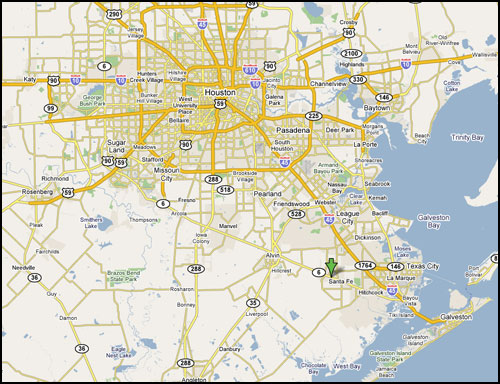

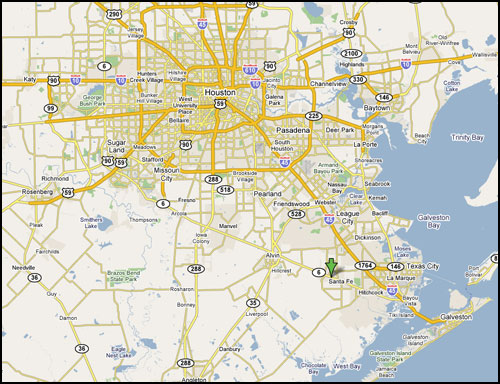

Alta Loma is a very small town in the Galveston area — you can read about its history here at the Handbook of Texas Online. Note that in recent years it’s been swallowed up and incorporated into the larger town of Santa Fe. Cimmerian readers have read all about how the Chamberses moved down there to farm and sell fruit door-to-door. Reading the Handbook of Texas entry brings home how difficult a life that must have been during those years.

So that confirms de Camp’s guess (probably a guess Norris gave him) of “probably 1918.” But it brings up another problem with the dating. If, as de Camp states, the Chamberses didn’t move down to Galveston until “after the Armistice of November 11, 1918,” then how could this photo have been taken the previous February, a full nine months before they moved? Doesn’t make sense. Perhaps they went down on a scouting trip of sorts with the Howards in February? Or perhaps de Camp’s information about them moving in November of 1918 was wrong, and they actually moved a year earlier? Norris sounded a bit vague on exactly when they moved down there, and he himself was far too young to have any memories of the years the family spent down south, so it’s possible he misremembered to de Camp. Someday I’d like to spend enough time at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, where the de Camp papers are kept, to get to the bottom of this and many other mysteries.

I’m having Norris make me a scan of the photo, both sides, so I’ll know more information directly, and will report any updates here. It will be interesting to see how much more detail is in the original photo, if any. I dearly wish the other three or four rumored photos had survived — who knows what they would have shown us? A group photo of the entire Howard trio at that age would be wonderful to see. Maybe they are still out there somewhere, waiting to be found. Stranger things have happened — Rusty Burke and Patrice Louinet found the photo of REH outside his house with Patch a mere few years ago, at the house of another old lady who knew the Howards in her youth. I’ve got to get Rusty to write up that interview and experience in The Cimmerian, it’s a doozy of a yarn.

Thank God for people like Norris Chambers and Marjorie Leeton, keepers in their own small way of the Howard flame, both via their memories and by way of a most miraculous photograph.