The Cimmerian V4n3 — June 2007

Edited by Leo Grin | Illustrated by Andrew Cryer

40 pages

This issue was printed in two editions. The deluxe edition, numbered 1–75, uses a black linen cover with foil-stamped midnight blue text. The limited edition, numbered 76–225, uses a midnight blue cover with solid black text.

DELUXE COPIES DESTROYED: 0

LIMITED COPIES DESTROYED: 40

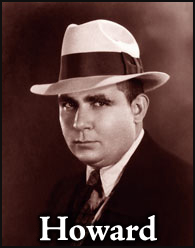

Features a look into REH’s influence on Heavy Metal music, a piece on Bran Mak Morn as a classic American hero in a European setting, a deep exploration of the history of the Howardian honorific “The Father of Sword-and-Sorcery,” a wonderful essay on the thematic undercurrents coursing through Howard’s Solomon Kane tales, poetry by Anthony Avacato, a rough-and-tumble Lion’s Den, and more.

EXCERPTS:

With the exception of a few earlier albums, most of Manowar’s covers have been painted by Ken Kelly. These usually depict a warrior that could be considered Manowar’s mascot. The figure in question is a giant of a man with long black hair, most often bearing battle wounds, always with sword in hand, and sometimes a war hammer in the other hand. Broken chains dangle from his wrists, and the fires of Hell burn behind him. Bodies of his slain enemies are often strewn about, demons fly behind him, and women of human and succubi persuasion are sometimes seen kneeling at his feet. Sometimes he bears the trophies of battle (skulls or severed heads, large gold rings, etc.), other times he triumphantly carries a flag, leading his soldiers out of the gateway to Hell. But the most important thing about this muscular figure of war and death is his face…his features are never shown, his face always shadowed in darkness, burning red eyes the only discernible feature. This, to me, is a representation of the narrator of REH’s poem “A Word From The Outer Dark.” He is the Dark Barbarian, bringing fire, steel, and death to all in his path. I don’t know if this is intentional or not, but it’s a powerful connection to the spirit of REH’s work.

— from “‘An Iron Harp Played Through a Marshall Amp” by Scott Hall

In his legends of the Picts REH presents us with a Celtic Twilight, a story of the decline of pre-Celtic Britain in the face of new threats. He explicitly links the Picts to America-in “Men of the Shadows,” he goes so far as to describe the Picts as originating in the Americas. In “The Black Stranger” and “Beyond the Black River” the Picts are described as no less than fictional, Hyborian Age equivalents of Indians, to the point where it was easy for Howard to later rewrite the Picts in “Black Stranger” as Indians in “Sword of the Red Brotherhood,” a pirate tale set in seventeenth-century America. His Pictish tales thus are distinctly American stories which themselves manage to colonize a European setting. In doing so, they recapitulate American history with a vengeance.

— from “Worms of the Frontier” by David A. Hardy

[Lin Carter’s] main idea is that Howard created Sword-and-Sorcery with the popularity of Conan, with Solomon Kane as more of a precursor to full-blown Sword-and-Sorcery. There’s a lot of critical byplay at work here. De Camp’s thoughts on fantasy were often influenced by the younger Carter — he once remarked he had never realized the position of William Morris in the imaginary-world tradition until reading one of Lin’s fanzine articles. In turn, it was de Camp who included a Solomon Kane story in one of his heroic fantasy anthologies, possibly firing Lin’s imagination about the importance of Kane in the formation of the subgenre.

— from “The Father of Sword-and-Sorcery” by Gary Romeo

Throughout Kane is repeatedly described in diabolic terms: “This Solomon Kane is a demon from hell,” “he comes from hell,” he looks “like-Satan,” he is “ghostly,” his face includes the “satanic darkness of his lowering brows” and a “Mephistophelean trend of the lower features.” A Puritan, warped by Howard into demon, devil, and ghost! How different from the Conan stories, where the similes and metaphors revolve around the fierce predators of our natural world. Howard occasionally describes Kane in such a manner, but more often than not far darker imagery threatens to overpower us.

— from “‘Raising Kane” by Paul Shovlin

The “riot of anachronisms” charge is simply true. There is the celebrated case in which a Howardian protagonist shoots Tamerlane with a pistol some centuries before pistols were invented. Remember that de Camp was soon to be the author of The Ancient Engineers and Great Cities of the Ancient World. He knew a great deal about ancient technologies and when and how they developed. The Hyborian Age is indeed a riot of anachronisms. One may reasonably ask why the Aquilonians, who can make heavy plate armor and field large squadrons of heavy cavalry, don’t simply conquer the entire Hyborian world, since they are on about a fourteenth-century level and much of the rest seems on about the technological level of the Romans, or even lower.

Furthermore, a society which can make plate armor can make other large metal objects, like church bells, or, if they have gunpowder, cannons. Remember that in our world full-plate armor came into use about the same time as the first cannons. One also wonders why this technology doesn’t diffuse throughout the civilized lands of Hyboria. It can’t all be rigidly-guarded state secrets.

It was precisely this kind of detail that so exasperated Sprague’s colleague Fletcher Pratt about Howard. But Sprague being, I think, much more of a romantic, was sufficiently caught up in the sweep and color of Howard’s storytelling that he was willing to forgive much. The important point is that this does not turn Howard’s faults into his virtues. Some of his works do show signs of haste. Some do show careless research. It’s not as if Howard is the only writer to commit such sins. Even Shakespeare has a clock striking in the Rome of Julius Caesar.

— Darrell Schweitzer, writing in The Lion’s Den