A JRRT Birthday Post From Grognardia

Monday, January 4, 2010

posted by Deuce Richardson

Yesterday, James Maliszewski, proprieter of the Grognardia website, as well as a Friend of the Cimmerian, wrote up a thoughtful birthday post regarding Tollers. Primarily, the entry is concerned with the influence of the appendices for The Lord of the Rings upon James’ early role-playing gaming career. It’s a worthy piece and I advise the RPG-inclined to check it out.

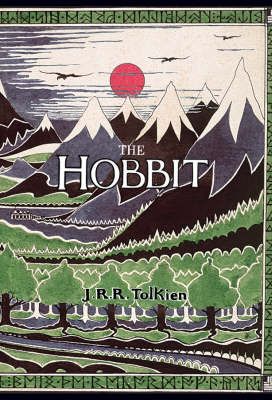

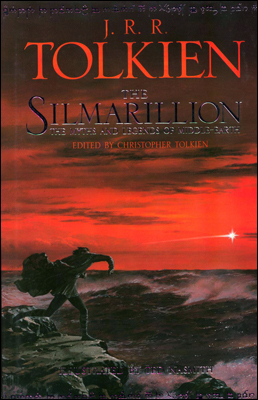

However, while not exactly a quibble, I think it worth mentioning that Tolkien did not in reality “box in” or over-explicate his sub-creation of Middle-earth as much as some surmise. If one excludes The Silmarillion and considers only The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, then JRRT left vast areas of his world unexplored and saw fit to let many metaphysical questions remain unanswered. The only region given a thorough going-over was north-western Middle-earth and even that had large areas about which little was revealed, whether in the tales themselves or in the appendices.

In contrast, Robert E. Howard had Conan personally visit many more far-flung regions (though it appears Aragorn came close to matching the Cimmerian in his own wanderings). In Howard’s (barely) post-Hyborian Age yarn, “Marchers of Valhalla,” he had Hialmar’s Æsir war-band nearly circumnavigate the globe on foot. In addition, while no official ‘appendix,’ REH’s “The Hyborian Age” essay goes a long way towards fulfilling that function.

Just something that occurred to me.

It was almost

It was almost