Cold Cuts

Friday, February 27, 2009

posted by Steve Trout

“It’s like some sick joke!” — Dr. McKenna

In my admittedly somewhat jejune research into Howard’s psychology, I’ve long questioned the Freudian interpretation of the father-son clash as primarily sexual, the so-called Oedipus complex.

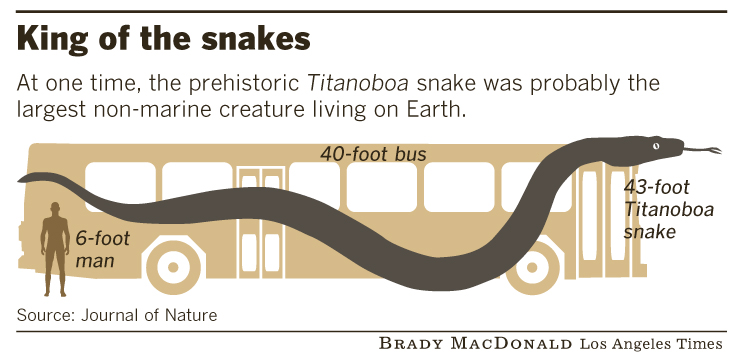

For this, and many other of Freud’s theories, to finally become accepted by the medical establishment, the modifying and corrective theories of Freud’s onetime disciple, Alfred Adler, have generally been adopted. Though considered another of the great Viennese psychologists, Adler is less well known to the general public; but to those interested in Howard and “Oedipalism” he is well worth looking into. Adler [1870-1937] suggested that the son strove not for mama’s sex but for “the laurels, the possibilities, the strength of his father.” He also suggested that this conflict was universal, based on the inferiority a baby inherits upon the realization that all other humans in his immediate environment are not helpless like him, but god-like beings of massive size and strength, with uncanny powers of food production, movement, etc. The development of character begins with how the child reacts to this weakness. On the one end, a child may remain convinced of his weakness, and demonstrate it to gain control through sympathy, and on the other side, the child may determine to become as powerful as the father (the dominant figure in the family) and thus begin the rivalry. It is not the mother that is at stake so much as the world; a blind striving forpower that Adler calls the “masculine rebellion.”

Adler says the infant “learns to overvalue the size and stature which enables one to open a door, or the ability to move heavy objects, or the right of other to give commands and claim obedience to them. A desire to grow, to become as strong or even stronger than all others, arises in his soul.” This is much easier to swallow than Freud’s sex-based theory — Freud was obsessed with sex, anyway.

One might speculate that at the ultimate extreme, the infantile urge is wanting to kill God and rule the cosmos; that should sound at least vaguely familiar to any of you longtime fans of Karl Edward Wagner and Kane. I think if you read Adler you can get a handle on why Howard valued strength, power and freedom, saw the world, perhaps, as an adversary, and get away from the notion that that means he wanted to sleep with his mother. My own browsing included his selection in Psychologies of 1930, his Understanding Human Nature (Greenburg, 1946), The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology (Harcourt, Brace, 1924) and a couple of edited “revivals” of his work published recently, whose titles I have no notes of.

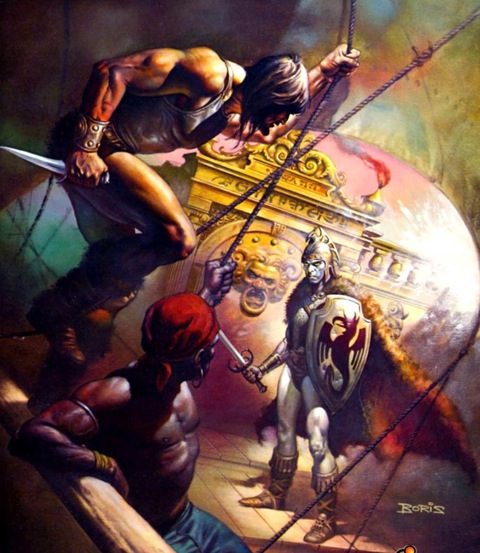

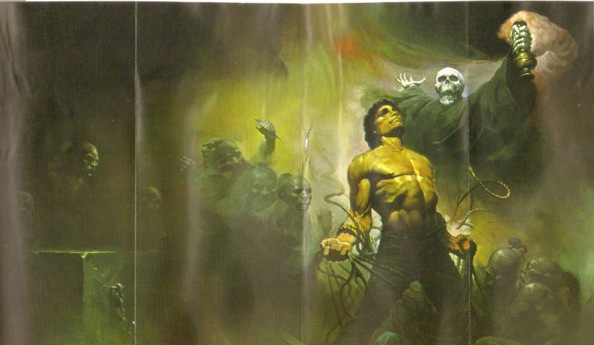

By all accounts, Dr. Howard was a man who projected power such as would seem daunting, and would make a great impression on a small boy growing up in his household. I believe infantile rage is somewhat (in my view) justified, and similar to the precepts of thought I was currently reading in Forrest McDonald’s Novus Ordo Seculorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution [University Press of Kansas, 1985]. I have also noted (thanks to Vern Clark) that Howard had used the idea of toppling God, or at least come close to it, in his portion of “The Challenge from Beyond.” Of course, gods (with a small “g”) like Atali’s brothers, various Lovecraftian monsters worshipped in isolated citadels, and Khosatrel Khel in “The Devil in Iron” (“he stalked through the world like a god…and the city of Dagon…worshipped him”) lie spread like litter across the paths of Conan, Esau Cairn, and Niord.

In a related note, I’ve spoken also of the Alpha Male concept and how the Adler discussion was very close to the idea that all males are born instinctively desiring to be Alpha. I’ve suggested that the source of Conan’s appeal was that we were seeing through the eyes of the ultimate Alpha Male, living vicariously the royal life we’ve felt our birthright since infancy — and make no mistake, even though Conan is only King in the later stories, in all stories he is the dominant character, powerful and aggressive.

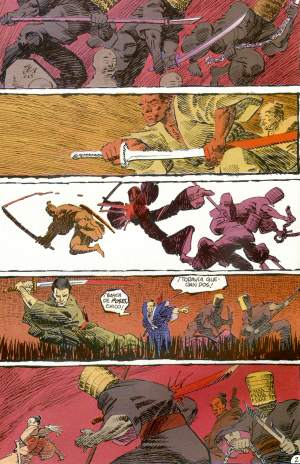

Recently in the bookstore, I saw a new coffee-table book on The Art of Sin City. I poked through it, and read the R.C. Harvey introduction. Miller had told this guy how his book Ronin had been an artistic turning point, and for some reason, I decided to go home and re-read Ronin. I’m not going to go into the plot too much, but the lead character, Billy Challas, is a freak. Born without limbs, he also possesses a “mind over matter” telekinetic power. Until he brings this power out, he is an exaggerated infant — limbless, helpless,dependent. He is repressing the bulk of this power because of an incident where he turned a neighbor kid who was tormenting him into a nasty spot on the wall, at which point his mother went postal and institutionalized him. But now, this cybernetic computer at the industrial complex he somehow ended up in is trying to unlock Billy’s telekinesis — through some kind of mental link, the computer-hive mind known as Virgo has him locked into a fantasy world where he has arms, legs and power — a masterless samurai, or Ronin, facing a demonic enemy and his minions. This fantasy somehow extends to envelope the people around him. And it is a violent fantasy, with the Ronin bearing a very sharp sword that, well… here’s how Dr. McKenna and his shrink work it out:

Dr. M: The power still exists [despite being repressed]… and Billy — he’d be unhappy. Armless and legless — he’d have to be unhappy. So what would he do?

Psych: Who knows? He’s not my patient. There’s no way I can talk about somebody I’ve never met. Still… he’d probably have a rich fantasy life…

Dr. M: Yes. Yes. And these fantasies — where would they come from?

Psych: Wherever. Fairy tales. TV. Movies. Like that.

Dr. M: And they might be violent?

Psych: Could be. Especially if he was angry.

Dr. M: Angry? He’d be raging! What else? He’d hate everybody! Everybody with all their arms and legs… he’d want to take their arms and legs and …and… …he’d want to chop…It’s like some sick joke! (laughs, a bit hysterically)

In the end, the multi-layered Ronin plot is, like Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream, a kind of satiric, psychological criticism of the sword and sorcery genre. But instead of the Freudian sexual overtones of the latter, Ronin is using the Adlerian themes of infantile helplessness transformed into rage. Remember this: helplessness means rage. Envy. Powerlessness can then easily turn to hate. Examples of Howard characters using a sword to dismember, behead, and otherwise carve up people are rampant in his works. It’s clear when you get Conan mad and give him a sword or axe, what happens to his enemies. Meat. And Howard gleefully paints each butchering stroke, to leave no doubt. Conan was, according to Fritz Leiber, the character into whom Howard “was best able to inject his furious dreams of danger and power and unending adventure…” Furious. Gleeful. And this takes us back to the bullies in his life.

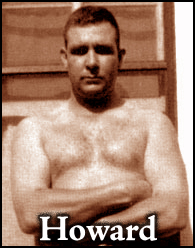

Despite the over the top exagerations of biographer/critic deCamp, there is no reason to doubt the fundamental story we get from Doc Howard, Tevis Clyde Smith, and Novalyne. Howard was, for a time, made miserable by a few bullies who were larger than him, and more numerous. (“overgrown”, older boys”, “half-again his size”, “no one to take my part”) And this had a profound effect on him. (“Unforgettable hatred”, “today.. crush his damned head… the way I would a cantaloupe,” left its mark on Bob until the end, and was responsible for much of his bitterness.) Of course Howard didn’t speak of this period much, or write of it to correspondents. It was a time of shame for him. Most hateful of all, I would think, was the fact that he was helpless. Like a baby, in the grip of the stronger, bigger kids. He entered in to build his body up because of it. Perhaps the fact that he became ill at an age where he was just beginning to walk played a part.

There is another guy who built himself up, like Howard, devising his own low-budget body development plan using auto parts he found in a vacant lot:

“It came from deep-rooted insecurity. You kind of create a muscular shell to protect that soft inside. You try to build yourself into the image that you think people will respect, and it tends to get a little extreme. It’s like playing God, rebuilding your body in your own image.”

— Sylvester Stallone.

Playing God — the opposite of helplessness. Insecurity, protecting the softness inside, seeking respect (or at least to be left alone) — and getting a little extreme. These all seem to describe Howard very well.

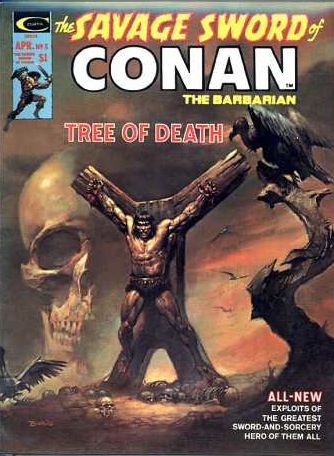

Conan, the mighty swordsman and most successful projection of furious dreams of power, is someone we seldom think of as helpless — yet hung on a cross, dead vulture at his feet, this is how Olgerd Vladislav finds him in “A Witch Shall Be Born.” We are told that Conan looks with revulsion on Khauran, the city that had betrayed him, and left him here “like a hare nailed to a tree”. Once his hands are freed, Conan is quick to demonstrate he is no longer helpless — he pushes his helper Djebel away, grabs the pincers with his swollen hands and pulls the nails from his feet himself. A stunningly improbably feat of toughness, but imperative to Conan’s way of being — and he knows the desert men are judging him to see if he’s fit to live, so it is not just pride or self-image, but survival, that drives the act.

Once he has usurped the Zaporoskan’s leadership within the horde, Conan has to deal with Olgerd. Practicality would suggest he be killed — yet he did save the Cimmerian’s life(however rudely and unkindly), so Conan would violate his code, I think, by killing him. Yet Olgerd has done a sinful thing in that he witnessed Conan in his helpless state, so before banishing him, Conan renders Olgerd helpless by breaking his sword-arm. Like the Ronin character, who avenges his limbless helplessness by rendering his enemies limbless, Conan erases his former helplessness by inflicting it on Olgerd. And with Constantius, the true author of it — well, what else is there to do but nail him up on a cross of his own?

Finally, one can surmise that hating helplessness, watching his mother struggle and fade in her lengthy, debilitating illness, Howard’s desire to go out “quickly and suddenly, in the full tide of my strength and health” (as he wrote to August W. Derleth) is his final trumping of the possibility of his ever being helpless again, and should be considered a factor in his plans to suicide.