Sunday, April 27, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

I think it’s fair to say that during 2007 we here at TC‘s Centcom were both anniversary-minded and Tolkien-minded, but fell down on the job when it came to being Tolkien anniversary-minded. In other words, we celebrated the diamond jubilee of “The Phoenix on the Sword” and the miracle of filial piety that saw The Children of Húrin into bestselling print as a near-novelistic standalone, but we spaced on the 30th anniversary of The Silmarillion, that gateway to the First and Second Ages of Middle-earth. Unfinished (but unbeatable) tales, false starts better than the true finishes of most fantasists, and all the priceless detritus of what Tom Shippey termed “intense and brooding systematization” would follow, but the 1977 book came first — as it also did, in its earliest form of The Book of Lost Tales, in Tolkien’s creative life.

The Simarillion‘s thirty years at large in the world have played out as something of a Thirty Years War. Ted Nasmith’s painted realizations of Silm.-scenes are far more vivid than the poor-visibility-or-soft-focus efforts of certain mistier Tolkien illustrators, but he was fairly mild-mannered when he described the work as “magnificent but underappreciated.” It occasionally seems to me that Mein Kampf hasn’t been reviewed as vitriolically and vindictively as The Silmarillion. Much-purchased upon publication but anecdotally little-read, dismayingly “like the Old Testament,” “as boring as the endless legalistic pedantries of Leviticus,” “a telephone directory in Elvish,” or “a stone soup of the most mouth-mangling names ever seen in print.” One worthy speculated that someone capable of reading The Iliad “for pleasure” might just about be able to enjoy The Silmarillion — his disbelief that any such freak existed, or should be permitted to exist, was so tangible it might as well have been in Braille. The Time reviewer back in October of 1977 bemoaned the absence of “a single, unifying quest” and “a band of brothers for the reader to identify with.” As it happens The Silmarillion‘s central narrative does indeed feature a single unifying quest, and it’s the stuff of nightmares, the nightmares endured and perpetrated by a band of literal brothers hagridden by an overbold oath sworn in haste and repented at sorrowful leisure.

(Continue reading this post)

Thursday, April 24, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

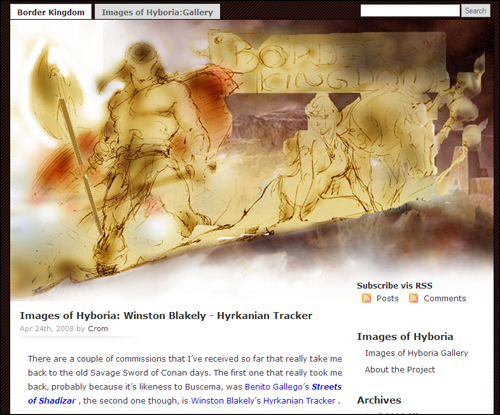

Cimmerian reader Zack Esser has created a new website dedicated to all things Howard and fantasy. It’s called BorderKingdom, and it promises to be, among much else, a prime showcase for Hyborian Age art. He has a blog that will regularly publish new artwork and essays, and a gallery titled Images of Hyboria. Head over and give it a look.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

Cimmerian readers are aware of the intellectual battle that has been waged in The Lion’s Den about H. P. Lovecraft since the release of “Lovecraft’s Southern Vacation” in TC V3n2 (February 2006). One of that discussion’s prime participants, Graeme Phillips from England, has recently published the first issue of a new ‘zine dedicated to the man who was Providence. Titled Cyäegha, and produced in a run of sixty numbered copies, the first issue is dedicated to the Belgian Mythos writer Eddy C. Bertin and runs twenty-eight pages.

For a contents listing and ordering information, go here.

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

posted by Leo Grin

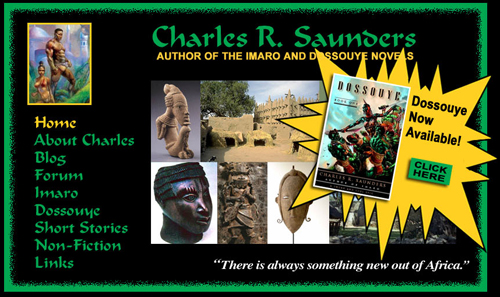

My copy of Dossouye is ordered and on the way, and I’ll have more to say about it another time. Until then, head over to Charles Saunders’ brand new website, complete with blog, links to interviews, and of course information on his new book.

Friday, April 11, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Any given year is a demonstration of mortality in action, but so far 2008 has been especially hellbent on inaugurating the afterlives of figures who had permanent luxury suites in the Tompkinsian pantheon: George MacDonald Fraser, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Fagles, and now Charlton Heston.

No sooner was I surfing the first wave of obituaries and career summaries than I was muttering and cursing. Everything else Heston did was being reduced to flotsam bobbing atop each half of the parted Red Sea, or dust beneath Judah Ben-Hur’s chariot wheels. It’s difficult to be objective about those movies because they became the Easter season equivalent of the Yule log, always on the TV screen in the background. When I try to watch either, it isn’t long before I wish someone had spiked the holy water. Oh, Ben-Hur retains some interest because of the involvement of Gore Vidal, Yakima Canutt, and a young assistant director named Sergio Leone, and the early scenes at the Egyptian court in The Ten Commandments are entertaining, mostly because of Yul Brynner’s seething Ramses (had he not gotten all that emoting out of his system, would he ever have been able to play the robot gunfighter in Westworld?) But I prefer Heston’s mid-career parts, when cracks in the Michelangelo-sculpted marble and verdigris on the gleaming bronze began to be detectable, so I was glad to find Manohla Dargis’ “The Man Who Touched Evil and Saved the World” in the New York Times: “My fondness for Mr. Heston can be traced back to the films I saw growing up, most important, his great dystopian trilogy, Planet of the Apes (1968), The Omega Man (1971), and Soylent Green (1973).” Had Ms. Dargis bethought her of how Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) ends, she might have reconsidered the second half of her tribute’s title, but I’m with her on the Dominus of Dystopia; whenever I read Howard’s “The Last Laugh” (an overheated discussion of which concludes an essay printed in TC V5n1), despite the probable Conanomorphism of the protagonist’s appearance, I imagine Charlton Heston, the last word in last stands and the first choice for the day after the end of the world.

(Continue reading this post)