Steve Tompkins and the book that never was….

Sunday, April 19, 2009

posted by Leo Grin

Print This Post

Print This Post

Here’s something I commissioned for the print edition of The Cimmerian but never used.

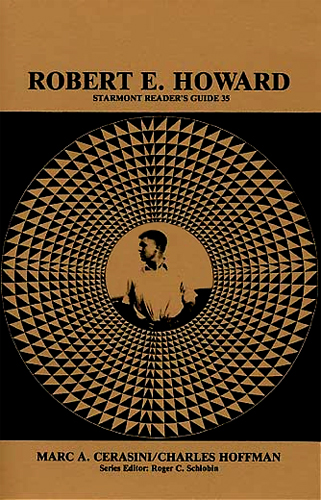

A few years ago, Charles Hoffman and Marc Cerasini undertook a revision of their old Starmont Reader’s Guide: Robert E. Howard, which was first published in the late 1980s. Wildside Press was supposed to bring out the updated version circa 2006, but — like so much else at that press — the book fell through the cracks and never appeared. At the time, I charged Steve Tompkins with interviewing Cerasini and Hoffman, and planned to have the result run in TC concurrent with the release of the book. With their revised tome MIA, however, I tucked the (lengthy and interesting, as it turned out) interview into my files, against the day when Wildside would finally get its act together.

Well, since then whole years passed, the print Cimmerian ended its run, and now Steve himself is gone. So I figure it is as good a time as any to finally unleash this interview into the world. It’s actually a very enlightening discussion — Steve asked many deep, intelligent questions, and really brought out the best in the authors. For those of you who never bought the print Cimmerian, this post is also a peek at what my TC print subscribers were regularly exposed to: Howard articles of a depth and breadth not to be found anywhere else.

So here we go: the late, lamented Steve Tompkins interviewing Howardists Charles Hoffman and Marc Cerasini about their critical volume on Robert E. Howard, plus much else. Take it away, old friend:

STEVE TOMPKINS: For each of you, what was your first exposure to Howard? If as seems likely you made the acquaintance of Conan by way of the Gnome Press or Lancer collections, please tell us what you made of the presence of posthumous collaborations and pastiches.

MARC CERASINI: I can recall my first exposure vividly. I was maybe thirteen or fourteen years old and had purchased issue # 11 of Castle of Frankenstein magazine for thirty-five cents. Inside Lin Carter had a column touting the new publishing releases and he covered the Conan books extensively. Now, the first Lancers had just come out and I was eyeing them anyway because of the beautiful Frank Frazetta covers (I knew Frank’s work from Creepy and Eerie — Vampirella had not come out yet.) On Lin’s recommendation — and the fact that my parents were going to Expo ’67 and felt guilty about leaving me behind and so footed the bill for a shopping spree — I went to my local mall and purchased the first four Conan books, and an Aurora model of Blackbeard the Pirate.

On a sunny afternoon in June I read “The People of the Black Circle” and I was hooked — changed forever. Prior to my exposure to REH, I was reading a limited amount of science fiction and horror (The ABC’s of course — Asimov, Bradbury and Clark; as well as some John Wyndham; HG Wells and Jules Verne; and the classics Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Werewolf of Paris by Guy Endore). I also read too many comics: Marvel superheroes (which I discovered with Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man), DC war comics like Sgt. Rock, Enemy Ace, Johnny Cloud, the Navajo Ace, Star Spangled War Stories where U.S. Marines battled dinosaurs and the Japanese on remote South Pacific Islands during World War II, and even movie and television tie-in books. One irony of my writing life is that I grew up reading Michael Avallone’s Man From U.N.C.L.E. novels and now I’m writing 24 novels for HarperCollins.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: My first exposure to Howard was through the Lancer Conan paperbacks. There were four out at the time, the latest being Conan the Usurper. It was Marc who turned me on to them, so he got there first. I remember him telling me, “You gotta see these!” My eyes nearly popped out and I started drooling, or at least it felt that way.

Now just to clear something up, people might assume, “So, it was the Frazetta covers.” The answer to that is, Yes and No. It was the whole packaging — the typeface and back cover copy, as well as the paintings — that did the trick. There was that bit on the back of each one; “Meet Conan, the gigantic adventurer from Cimmeria — and discover one of the greatest thrills in modern fiction.” Also, stuff like “A Hero Mightier than Tarzan…Adventures More Imaginative than Lord of the Rings.” Even the little Lancer chess piece logo and those purple page edges Lancer used to have added to the effect. The Ace editions of Conan had the same Frazetta covers, but not the same magic.

As to the pastiches and posthumous collaborations, I didn’t mind so much at first. So de Camp completed “Drums of Tombalku” in the first book. That only made sense, since you didn’t present unfinished stories in mass market paperbacks back then. But time went on, and it got worse and worse. By Conan the Wanderer half the stories were non-Howard. The Lancer series jumped the shark with Conan the Avenger. The only Howard was one half of “The Hyborian Age,” followed by Björn Nyberg’s pastiche. The previous volume, Conan, had “The Tower of the Elephant” and “Rogues in the House.” We couldn’t wait to get the next one, and then…we were aghast. I also remember an occasion where some review said, “Experienced fans agree that you can’t tell where Howard leaves off and de Camp begins,” and Marc joked, “I must not be an experienced fan.”

STEVE TOMPKINS: Marc, in the “About the Authors” section of the original Starmont Reader’s Guide, we learn that “while still an undergraduate, [you] taught an accredited course on Robert E. Howard and popular culture at Ohio University.” How did that come about? Was it a seminar or a lecture course? Did you encounter much skepticism from faculty members? Were the students taking the course expected to produce a term paper or answer essay questions for a final exam? What if anything did you draw upon for secondary literature on REH back then? At that early stage, were you trying to tie Howard in with classic American literature as you would go on to do in your TDM article “Come Back to Valusia Ag’in, Kull Honey!” Revisiting the experience in 2005, what are your thoughts?

MARC CERASINI: The course at Ohio University was a rare moment in time, a perfect storm of academic chaos mingled with the first early glimmerings among the elite gatekeepers of academia that popular culture might be more than just crap. Two professors I respected, Dr. Reid Huntley and Dr. Mark Rollins, both mentioned that the literature department had a space open for undergraduates who wished to teach a special, accredited lecture course on a particular aspect of American letters they deemed neglected. Sadly, both professors decried the fact that the program itself was being neglected and I stepped in at the last minute. I had less than a week to prepare my course curriculum for approval by the powers that be. My original concept for the course was something like “Comic books as literature” or some such, but as I put the class together I realized I couldn’t neglect the pulp fiction roots of certain comic-book icons (Doc Savage to Superman, The Shadow to Batman, etc.) so I expanded the course to something more like “Pulp Fiction, Comics, and Modern Western Mythology.”

As I wrote my proposal to submit to the literature department’s board, the pulp fiction part kept getting larger, the comic book aspect shrinking. In the end, three of the nine weeks of the course were spent on Robert E. Howard’s fiction. It was a real course, a one-time thing, and my students were expected to produce papers, one every three weeks. My secondary sources for REH were the issues of Amra I’d collected, and the Mirage Press anthologies from same. I of course tied REH in with the traditions of American literature because he fits there — James Fennimore Cooper, Melville, Jack London all come to mind, and I said pretty much the same in the essay you cited in your question. I met very little skepticism from the professors, but I think they were just happy to have the student teacher spot filled for a semester.

Looking back now, the best part of this course was that nine years later I ran into one of my former students (then a DJ at a Manhattan radio station) and he was still reading Howard! That’s my triumph.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Chuck, in the “About the Authors” section we’re also told that you have private detective and carnival-hand experience. Have those jobs ever been of use in your critical writing? In your “Hard-Boiled Heroic Critic” piece in TC, you mentioned that “Conan the Existential,” which not only put you on the map of REH criticism but helped to justify the very existence of that map, was deemed by some to be “ridiculous.” Would it be fair to suggest that those who reacted so dismissively might have felt threatened? Did writing “Existential” leave you with larger ambitions in terms of Howard criticism that led directly to the collaboration with Marc?

CHARLES HOFFMAN: I only worked as a private investigator and carnival hand a short time in my youth, when one has time for those sorts of things, and just included them in my bio to sound cool. I was an investigator for Pinkerton, and did overnight surveillance of warehouse workers who were ripping off their employer. Now here’s the interesting thing about that job: the supervisor at Pinkerton who hired me had a Frazetta print on the wall in his office. It was the one with the polar bears pulling the sled. I commented on this, and it lead to a discussion where I learned he was extremely knowledgeable about REH. He had even had a Weird Tales collection, which had been lost when his basement flooded. Now get this: he had even talked with the sheriff of Cross Plains at some point, who told him that Howard, in his final days, had not been known to sleep. This was actually the first time I had heard about REH experiencing sleep deprivation prior to his suicide, this being 1976. Still — small world, huh?

After “Conan the Existential” appeared in Ariel, it was greeted with some derisive comments in some fannish-type venue. I can’t say if they felt “threatened,” since I have no way of knowing what they were thinking. It’s just a hunch, but I would attribute it more to their being fretful about attracting scorn and ridicule from fine-art types. This was before Leslie Fiedler coined the term “middle-brow literature” in an effort to indicate that there’s a pretty wide stretch of territory between universally-acknowledged classics at one extreme and stuff with little or no merit at the other. I think there’s still some insecurity at work in the back of the minds of people who are into some form of popular culture — some nagging doubt that what they’re doing is bogus, and that the “real thing” is somewhere else. People can trip themselves up over this. In C. L. Moore’s “Shambleau” there’s a line that says there’s a part of the soul that’s a traitor. Another line I recall is from Thomas Harris’s third Hannibal Lecter novel, Hannibal: “Never agree with your critics in an effort to gain their approval. It is the worm that will destroy you.” And as an aside, isn’t it something how Marshall McLuhan dropped off the intellectual landscape since his death?

Now, did any of that clear up anything, or just make it worse?

STEVE TOMPKINS: Collaboration is a fighting word for many Howard devotees; luckily, there was nothing posthumous about yours. How did the two of you become collaborators? Did your visions for what became the Starmont Reader’s Guide dovetail from the start? How much editorial input did Roger C. Schlobin provide?

CHARLES HOFFMAN: As to how Marc and I came to collaborate on the book, the answer is the book just sort of grew out of the many discussions we had about REH over the years. The book itself started small. We started to compose a small pamphlet size essay, that was to some extent inspired by — and in reaction to — de Camp’s Blond Barbarians and Noble Savages. It was to be a sort of essential REH reading list, with brief explanations of the significance of the stories chosen.

At some point, we realized that we had enough to say about REH to write a book-length critical study. We started in earnest on it in 1979, based on sheer faith that we would find a publisher. The first part we wrote was the Bran Mak Morn chapter — having decided to leave the biographical first chapter till later — followed by Solomon Kane. We worked on the book on-and-off for about five years, writing first on electric typewriter and, starting around ’83, on Kaypro computer. Marc and I moved to New York City late in 1979 to seek careers in publishing. We shared an apartment, which made collaborating easy. We hammered out a lot of it together sentence by sentence, Marc pacing about while I wrote out what we came up with in longhand on a notepad. This would all get transcribed, and we would polish it up later.

Around 1981 we met Robert M. Price and S. T. Joshi. S. T. had already done H. P. Lovecraft for Starmont, and showed us a copy. We contacted Roger Schlobin at Starmont and soon had a contract, so we ended up writing the better part of the book knowing it would be coming out from Starmont. Schlobin edited it with a pretty light hand; we just had to conform to the Starmont format.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Chuck wrote in the aforementioned TC article that the Starmont Reader’s Guide “did not appear in print until three years later, in 1987, but it was in ’84 that we put the finishing touches on it and sent it to the publisher.” Why the delay? It must have been maddening for publication to be delayed while the field was revolutionized by events like the arrivals of The Dark Barbarian and One Who Walked Alone, or a breakthrough like the publication of a tamper-proof “The Black Stranger.” Did you consider “reopening” the manuscript? Or would that have been a nonstarter?

MARC CERASINI: We did reopen the manuscript when an advance copy of Dark Valley Destiny became available. I was aware of Blue Jay Books when that ill-fated publisher started up. I made the call to the Editor-in-Chief, took a subway from my job on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and brought home a bound galley that night. I devoured the volume in one evening, Chuck the next. We incorporated as much as we could into our page proofs, but the Starmont House volume was pretty far along by then so naturally we couldn’t do as much as we would have liked.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: I don’t know why there was a three-year delay before the Starmont book came out. I guess Starmont just had titles scheduled ahead of ours. Of course it was frustrating, because we were eager to see it in print. Now history is repeating itself. I had hoped the new edition would be out in time for the REH centennial, but that’s looking less and less likely. I do hope to see it in my lifetime.

STEVE TOMPKINS: At the risk of prying, did you have any major disagreements over content?

CHARLES HOFFMAN: There were no major disagreements that I recall. The composition actually went pretty smoothly. The ideas and energy just flowed back and forth like a good game of tennis.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Chuck, your excellent article “Cosmic Filth: Howard’s View of Evil’ in The Dark Man #3 is something of a do-over, in that you write of “The Pool of the Black One” “This is one of his most underrated works, so much so that Marc Cerasini and I overlooked it in our Starmont Reader’s Guide.” Was it difficult to skip so many second-tier Conan stories? Any others, like “Pool,'” that you wish you’d squeezed in?

CHARLES HOFFMAN: Yes, some Conan stories worthy of commentary were left out, but we just accepted that as an inevitability. As one of our reviewers, Stefan Dziemianowicz, pointed out, Conan still gets a Conan-size share of the book.

Funny how you should mention “The Vale of Lost Women” and “The Pool of the Black One” in practically the same breath. As Fred Blosser noted, Patrice Louinet totally blew off my comments about “Pool” when writing “Hyborian Genesis.” As for “The Vale of Lost Women”; if at first you don’t succeed, try try again. “Vale” and “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter” will be compared and contrasted at greater length in a future essay I’m planning, to be titled “Passion’s Barren Bliss.”

MARC CERASINI: The Pool of the Black One has always been one of my favorite stories. As a pure display of Conan’s smarts and fighting prowess there are few better examples. I also found the fantasy element to be eerie and well portrayed. However, what most interests me about this story nowadays is not the monsters and magic, but the sociopolitical interplay of the characters.

Howard describes in detail Conan’s rise and Zaporavo’s fall. He compared and contrasted their personalities throughout. We see Conan crawl aboard the pirate ship Wastrel as a desperate fugitive, to face abuse and disdain from Zaporavo, the ship’s morose and imperious Captain. Then Conan is tossed before the mast.

Howard dramatically illustrates how Conan rose from a lowly seaman to master of that ship, first by killing the bully sent by the crew to test him, then by winning the rest of the crew over by drinking, gambling and cavorting with those below the mast. Note that once Conan kills the bully sent to bait him, he never again uses his physical prowess to intimidate his fellow crewmen. He earns their trust and respect instead. This all leads eventually to Conan’s murder of Zaporavo and claiming the pirate’s ship and his mistress Sancha.

What this narrative progression suggests to me is that Robert Howard — the man — understood intellectually what he had to do in order to fit into the conventional world of Depression-era West Texas. By that I mean put on a suit and learn some social conventions to get through public/social events, to marry Novalyne, go to church on Sunday, have brunch with the school principal or the bridge club or whatever. But he just couldn’t bring himself to do it. Something about Howard’s constitution compelled him to recoil from a conventional life. Howard really did believe his writing “would go to hell” if he put on a suit and socialized with Novalyne, and he was probably right.

Tom Wolfe might say that Howard had the perfect emotional tools to become an artist, i.e., REH felt alienated from society, yet still a part of it — he felt the artist’s isolation. Yet despite this alienation, Howard saw the epic spectacle of life around him — in the boom town where he was raised, and in the volumes of history he read. And Howard was a keen observer of human nature — we know this for no other reason than because Howard wrote comedy, which is no mean feat. Death is easy, comedy is tough.

It’s pretty clear that there nothing chivalrous about Conan’s actions. He is not portrayed as a heroic figure. Conan’s rescue of Sancha and the crew are the result of enlightened self-interest, not selflessness. We’re talking Ayn Rand, not Sir Walter Scott. Conan didn’t kill Zaporavo because the Kordovan was a dour and aloof man, or even a bad captain, though arguably Zaporavo was all of those things. Conan murdered him to get ahead.

With this notion in mind, I wonder if Howard intended the name “Sancha” (Conan’s “sidekick” in this story) as an ironic counterpoint to the character Sancho Panza, the unsophisticated but quite practical sidekick in Cervantes’ Don Quixote de la Mancha. Cervantes’ novel is a satire of medieval romances that explored the antics of a character suffering from a romantic, hopeful, inspiring, yet ultimately misguided and deluded form of chivalry.

Howard may have been taking a subtle jab at polite notions of chivalry in “The People of the Black Circle” by referencing Cervantes’ character. Howard’s Kordova is a thinly-disguised Spain in its golden age, Howard’s Sancha is a much more streetwise and pragmatic figure than Sancho Panza. In fact, she is an edgy, modern protagonist.

Though a less flashy and obvious model than the colorful and violent Valeria of the Red Brotherhood, Sancha is something of a female Conan, too. A captured princess snatched by Zaporavo’s pirates, Sancha “learned what it was to be a buccaneer’s plaything, and because she was supple enough to bend without breaking, she lived where other women had died, and because she was young and vibrant with life, she came to find pleasure in the existence.”

This is an archetypal noir character Howard is describing, as pure an American literary invention as the Continental Op or Philip Marlowe. This passage and others in the Conan canon place Howard squarely in the American noir tradition of James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, and not with J.R.R. Tolkien or his legion of imitators.

As for “Vale of the Lost Women,” maybe folks just don’t like our interpretation, which seems to have become more controversial as time passes, though the interpretation itself has not changed. What Chuck and I are saying isn’t exactly politically correct these days, so maybe we should have made our point more sensitively. But we did prove our point, even if others don’t choose to see it.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Morbid curiosity prompts me to ask you about your very worst review, if there was one.

MARC CERASINI: I don’t recall a bad review for the first edition of our Howard study. Kirkus was very nice. So was Library Journal.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: Most of the reviews we got from publications like Extrapolation were fairly favorable, albeit a bit condescending. The worst panning we got was from Will Murray in Necronomicon Press’ Studies in Weird Fiction. The crux of Will’s beef was that Marc and I identified too much with REH on a personal level, and this affected our objectivity. Sometime later, at the Lovecraft Centennial Conference in Providence in 1990, we met up with S. T. Joshi, who seemed a little worried that we might be pissed at Will over his review. We assured him we weren’t. My only complaint is at the end of the review, where Will says our book had “much to recommend it” despite his criticisms. I only wish he had gone into as much detail about whatever it was he actually liked, as opposed to just being completely negative.

STEVE TOMPKINS: When did you decide that a revised and expanded edition was warranted? And how did you determine what the outermost edge of the expansion would be?

MARC CERASINI: I think we both saw a new round of REH scholarship emerging, and we both wanted to include recent revelations in a new edition. After a while it became more of a mission to get the book out there again. There’s always something new to say about Howard, and we wanted to rejoin the debate.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: I think this slowly began to dawn on us as more and more new information about REH came to light. For my part, I began to feel a definite need for a new edition sometime in the early 2000s. By that time the book had been out of print for a long time, and I did not want this particular accomplishment of ours to be forgotten.

The shape of the new version was determined by the notion that this should be a revised second edition, rather than taking on the aspect of a whole new book. The Starmont series had to do with science fiction and fantasy authors, so the emphasis of the original remained on fantasy — which is the best known aspect of Howard’s work, after all — with an additional chapter for horror, and one for all the other genres. This time around, we did not want to alter the study to the point of adding new chapters, or reconfiguring existing chapters. And I think it’s important to note that we have always regarded our book as an invitation for others to do more advanced studies about Howard. The spirit of the original and the new edition remains the same-to help readers who are just starting to look at Howard in a serious way to get up to speed. Why else bother to point out things like “Howard was fascinated by…the Picts!” All of us here know that. Think of it as kind of a Robert E. Howard for Dummies.

STEVE TOMPKINS: The 2005 version of your book is tougher on L. Sprague de Camp, although he isn’t a Reverend Griswold-style villain of the piece. The 1987 version deemed him “primarily responsible for the resurgence of interest in Robert E. Howard’s work,” but now he shares that eminence with Glenn Lord. In the discussion of Dark Valley Destiny the assertion that its “authors have laid the groundwork for all future Howard criticism” has been amended to read “These authors have laid the groundwork for future Howard studies by interviewing parties personally acquainted with the Howards before this generation passed on.” Conan Properties is now the recipient of a well-deserved slam, and you mention the crib-death of the Wagner-edited, Howard-only Conan series. Did the need for such changes seem self-evident when you returned to the book?

MARC CERASINI: That’s me chuckling — the more things change, the more they stay the same.

I just received an advance copy of the Del Rey edition of The Conquering Sword of Conan and realized that Chuck and I can now whine about the possible crib-death of the Wandering Star volume! With the trade paperback beating them to the punch, only true fans of the Wandering Star books are going to shell out two hundred bucks for something they already bought for sixteen and change. Of course, I’ll be buying a Wandering Star edition, so count me a whiner if it doesn’t show.

In L. Sprague de Camp’s and Lin Carter’s defense, if it hadn’t been for them I would never have heard of Robert E. Howard or Conan. For that I am truly grateful. The de Camps’ biography of Howard was the first, and so paved the way for a second or third or fourth down the line. That is also a good thing. Conan Properties? Yeah, that’s a shame. But what do you expect? To justify their existence CP should at least supply some measure of quality control. Who needs another movie like Conan the Destroyer, or another John Buscema Conan story?

To be frank, I feel more ill-will toward Donald M. Grant these days. While Don did a lot of wonderful things — most especially publishing Post Oaks and Sand Roughs and Novalyne’s memoir — I have to ask what freaking God gave anyone the right to publish bowdlerized versions of Howard’s Solomon Kane and Kull tales, to actually have them edited for politically correct purposes? This shortsightedness ruined what little legacy the Donald M. Grant books had. Beautiful volumes such as the two hardcover editions of Solomon Kane (both illustrated by Jeff Jones) are utterly useless because the text is corrupt, passages were altered, the race of a main character in “The Moon of Skulls” was changed, etc. It’s just sickening. Insane. There’s a special ring in hell for people who do things like this. This type of censorship is akin to today’s American academics who trumpet diversity and then try to get Thomas Sowell or Ann Coulter thrown off campus. No matter one’s sincere intent or political stripe, censorship is simply wrong. Intellectual freedom must be preserved.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: We now give credit to both de Camp and Glenn Lord for the Howard revival, not so much to diminish de Camp’s role, but to make up for slighting Glenn the first time. We tried to be fair to de Camp because I don’t think you can overestimate the importance of the things he did right. As for Dark Valley Destiny, even the first time out we described it as “long on facts but short on insights.” We didn’t find further fault with it because it came out just as we were putting the finishing touches on our book, and it was the Big New Thing. Of course, many people have subsequently found fault with de Camp’s research. He has also taken flak for his editing of Howard. We were willing to take the good with the bad up to a point, and were perfectly willing to regard him as a kind of “mixed blessing.”

However, the real ball-breaker was the whole Conan Properties debacle — endless Conan pastiches flooding the market, while Howard’s original tales were kept out of print for twenty years. Put that in caps — TWENTY YEARS!!! That is not so easy to forgive. In the new edition, we just matter-of-factly state that this has hurt de Camp’s reputation among Howard fans, which I’m sure you’ll agree is a pretty tame understatement. And yes, since we were updating as well as revising the book, we did consider it necessary to mention all this.

STEVE TOMPKINS: One of the striking through-lines of your book is the emphasis on the extent to which Howard dealt in, not necessarily subversions or perversions of biblical motifs, but certainly highly idiosyncratic and re-contextualized versions of well-known events and characters. Chuck revisited this area in his “Genesis Subverted,” one of the best REH essays of the past decade. Did you know going in to the Starmont Reader’s Guide that this was an element of his work that you wanted to highlight? Is a touch of the blasphemer useful to the aspiring fantasist?

MARC CERASINI: I don’t believe Howard had a strong religious faith — he would not have committed suicide if he possessed a real faith in something bigger than himself, and the grounding such faith provides. Rather I think the biblical references and subversions found in his work were the result of his fertile mind storing away “story” for future reference in his own fiction. Some of the best stories in literature are found in the Bible. For many, these are the stories they live by. For Howard the Bible was a rich vein to mine for his own fiction.

The Starmont House book needed to explore the religious element because right up until the middle of the twentieth century, it was virtually impossible to appreciate or even comprehend much of American literature without a thorough knowledge of the Bible. Think Herman Melville or Nathaniel Hawthorne. Howard is no exception in the sense that he used biblical allusions to make his point — check out “Worms of the Earth” or “A Witch Shall Be Born” for starters.

And by the way, the touch of the blasphemer is useful to a writer of any genre.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: We did not realize this was a key element to be emphasized when doing the Starmont Guide. Be that as it may, I think Howard would have found the Bible to be rich in source material. In his fantasies, he used history like clay, molding the Stygians from the Egyptians and so forth. The ancient Egyptians are featured prominently in the Old Testament, just as Rome is featured in the New. Howard would have appreciated the sweep and grandeur of the Old Testament, as well as a mythic resonance of the sort he strove to impart to his own work. He used biblical motifs to his own ends in creating his fiction, as many an author has done. I suppose someone somewhere might consider that blasphemous.

STEVE TOMPKINS: It was galvanizing from a generational point of view to read this in the Starmont Reader’s Guide: “In the sixties, around the time the Conan paperback boom was getting underway, movie audiences eschewed John Wayne in favor of an existential anti-hero of the old west called the Man with No Name. In the James Bond spy films, a pop culture sensation of the sixties equaled only by the Beatles, 007’s main interests are gambling, high living, and womanizing: saving the world is a secondary concern.” So Conan, who was made in a different, earlier decade, would seem in many ways to have been made for the decade in which he broke big. L. Sprague de Camp was pained by the rampant treachery of stories like “Vale of Lost Women” and “The Black Stranger,” in which Conan betrays almost everything and everyone except his intentions, anticipating not only the amoral ronin characters of Kurosawa and Leone but also a spaghetti western-steeped story like Wagner’s “Cold Light.” What do you think it was about Howard that enabled him in effect to reach the Sixties in the Thirties?

MARC CERASINI: Both Sergio Leone and Akira Kurosawa were influenced by the American hard boiled genre, mostly film noir, but I’m sure there was some American fiction that influenced them as well — and, of course, Howard emerges from this same tradition.

Kurosawa’s 1949 masterpiece Stray Dog is a straight noir film in the American mold. Kurosawa brought those same noir attitudes into his samurai films. His ronin heroes — who influenced Leone’s spaghetti Westerns — are not very different from the fedora-wearing denizens of American proletariat fiction who prowled the mean streets of New York, Chicago or Los Angeles.

Bond became popular in the 1960s for the same reason. Read Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels today and it’s apparent they are a clever fusion of traditional British espionage fiction with the hardboiled style of writing, a la Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, and Bond is a hardboiled character.

Conan’s treachery in “Vale of the Lost Women” and “The Black Stranger” mirrors the wheeling-dealing, amoral attitudes of James M. Cain characters. Conan’s sometimes harsh attitudes mirrors shamus Dan Turner, the Hollywood Detective who gleefully cracks “you can’t make catsup without smashing a few tomatoes.”

The anger and edginess of noir fiction was partly a reaction to tough economic times. Then — as now — hard work and dedication got you nowhere. The scheming underworld of cheap grifters, con men, racketeers, rape-o shit birds, hustlers, and pimps of hardboiled fiction portray human emotion and actions in the harshest terms, but at least in Howard’s day, such folks inhabited the edges of urban civilization. Nowadays they’ve moved to the boardrooms of America’s corporations. The scam hasn’t changed — only the stakes.

I also believe Howard’s appeal in the 1960s and 1970s stems from the strain of fatherlessness which infected and still infects the culture. Many members of the first generation of baby boomers felt alienated from their remote and overworked fathers — a subject poet Robert Bly explored endlessly.

Born and reared in the depths of the Depression, many boomer fathers never had a father of their own. Their fathers worked two or three jobs, or looked for work. Many men abandoned their families during the Depression, became drifters, took to the rails. The experiences of my own family during the Great Depression are not unique. My grandfather died while my father — the second oldest in a family of five — was only eight or nine years old. As soon as he was old enough (twelve maybe, because the family lied about his age) my father and his older brother were shipped off to the Civilian Conservation Corps. They lived in camps in the Southwest, in a barracks with dozens of other youths. These boys worked in the national parks and on large-scale construction projects for ten hours a day. The money they earned was paid to their families.

My father did this until he was eighteen. Then the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and he enlisted in the Army Air Force, where he served in the Eighth Air Force in their daylight bombing campaign against Germany. His two brothers joined the navy and fought in the Pacific.

The closest thing my late father had to a father of his own was Clark Gable, his commanding officer in the Army Air Corps. The war ended and my father married in the early 1950s, and two sons followed. My father was a professional — an architect — so he became even more isolated from the real world by the requirements of a white-collar job in that era. Read Philip Wylie’s sociological study A Generation of Vipers, or the novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit for two harrowing peeks at what career men like my father experienced in that rapidly-changing era. They went from Depression to war to marriage, moved quickly up the social ladder — yet were not really equipped for any of these roles because so few of them had role models for anything.

My father did his best, but he worked fifteen hours a day and golfed Saturdays — and golfing was part of work, a necessary networking activity. I recall going to the mall as a family on Friday night, watching Have Gun, Will Travel with him on Saturday night, attending church on Sunday morning. My father bought me books and encouraged me to read, but he wasn’t exactly Glenn Ford as Pa Kent in Superman.

Many of the baby boom sons of such fathers, or boys who had no fathers, found a positive role model in Howard’s fiction, in Howard’s heroes. I’ve met many Howard fans over the years, and a surprisingly large percentage of them had no father figure at all in their lives. This is, of course, and anecdotal observation and not scientific, so take it or leave it.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: This may owe something to the fact that Howard did not live a sheltered life.

He worked at crappy jobs and understood that a working-class person viewed the world in a different light than a well-compensated, respected professional. He saw a lot of the seamy side of life during the Cross Plains oil boom. He therefore understood that some boy scout, do-gooder hero might work fine for a fifteen-year-old reading the pulps, but that an adult graduate of the School of Hard Knocks reading about the same character was likely to snort, “Wow, what a sap!” Consequently he felt moved to create characters who were more “street,” like Conan.

Someone on the Web described Conan as not so much a good guy fighting bad guys, but a bad guy fighting worse guys. Still, he has his own standards, and eventually does right by the more defenseless characters in “Black Stranger” and “Vale of Lost Women.” Conan knows that he can’t do anyone any good without the power to impose his will on the world, and he knows and does what it takes to obtain and wield power. The people he screws over are “players” themselves — playing the same game and playing to win. It’s like mobsters killing other mobsters, yet trying to keep innocent bystanders from straying into the crossfire.

If Howard is accorded credit for nothing else, I think cultural commentators will note his pioneering status as a purveyor of sexy, violent entertainment. He may be granted recognition as the originator of the down-and-dirty “badass” type of hero.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Readers familiar with only the basic facts about Howard’s background might be surprised to see you assigning the son of a physician and a woman with lace-curtain pretensions of gentility to the proletariat. Also, Howard loathing the educational system to which he was subjected would seem to have been balanced by a reverence for learning, an attribute that, obviously unfairly, is often associated with the middle class. Readers might therefore be quite interested in your reasons for labeling him as working class.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: Yes, Dr. Howard was a professional, but he was a country doctor often paid in in farm produce. And REH did have some college. I consider Howard to be a “working class writer” mainly because he wrote for the pulps and not the slicks. The pulps would definitely be considered the blue collar segment of the literary world. Guys like Gibson, Dent, Cave, et al. worked at their craft — they didn’t play at it. I really think REH merits respect because he had the same no-nonsense approach to fiction writing, but was still able to produce high-caliber works like “Worms of the Earth” and “Red Nails.” I come from working-class roots myself, and share that sensibility. I had some friends who were exotic dancers, and pointed out to someone, “Nobody questions Heidi Klum’s right to earn a living by being looked at. These girls are just the blue collar version.”

STEVE TOMPKINS: “Worms of the Earth” occasions some of your most powerful passages, Howard’s best summoning your best into being. In the revised version of the book, there’s a new paragraph that perceives “Worms” as both a “modern allegory” and a “universal cautionary tale,” and even broaches the term “terrorism.” And of course terrorism frequently involves going underground both figuratively and literally, and in Howard’s story a tower that’s a symbol of imperium is brought down. Is it an uncomfortably short distance from the sympathy we feel when Bran declares “There is no weapon I would not use against Rome” to the antipathy we felt when recent enemies acted on the principle of there being no weapon they would not use against the current Rome? Also, you write “Howard’s story starkly depicts the truly horrific toll that all-consuming hatred can demand.” This prompts the thought that in his art if not his life, Howard was usually a reflective as well as a reflexive hater. Did “Worms” speak to you in an altered voice after September 11?

MARC CERASINI: I think we spoke in an altered voice after September 11 because the event altered my perspective, and I’m sure Chuck’s as well. I live in New York City so it was a very personal event. I remember the smoke on the horizon, the F-18s flying low over my backyard, missiles dripping from their wings. I smelled the burnt metal and burnt flesh for weeks, like everyone else in this city. And I knew a few people who died, too, if not well. Their stories are as everyday and common as they are poignant.

The force that murdered them and three-thousand others at Ground Zero and at the Pentagon was evil, pure and simple. Howard would have understood. In fact, I believe Robert E. Howard understood the nature of evil far better than his much-touted contemporary, H. P. Lovecraft.

Lovecraft didn’t really believe in evil at all. He was a secular humanist who found Cthulhu and his ilk terrifying because of their omnipotent isolation, their total disregard for human lives and human events. This is only natural considering HPL’s origins. Lovecraft was born among the trappings of wealth, in a grand house in Providence, Rhode Island. From this promising beginning, Lovecraft’s life was a slow and inevitable decline into poverty. It doesn’t surprise me that Lovecraft’s definition of evil can be described as a universe that doesn’t give a shit about his problems, a universe that doesn’t even notice because during the Great Depression, HPL’s plight was as common as dirt.

Howard roots are very different. He was born on the frontier, lived his whole life in rural areas. Someone who lives close to the land, who lives side-by-side with domestic and wild animals, has a very different view of the world than a city dweller. To them the forces of life and death are locked in a constant, visible struggle. The season’s change, foals are born, cattle slaughtered. The chicken axed for the Sunday roast was fed and nurtured by the slaughterer until it was fat and ready. In rural Texas hunters tracked, killed and dressed their game, and the travails of pioneers and Indians — not one generation removed — were on Howard’s ears from birth.

This life-or-death struggle made Howard very aware of the panorama of life around him, the frailty of life, the totality of death.

What’s telling to me is how much Howard loved his dog and how much he mourned its loss. At that moment, as a child, Howard probably came to regard death itself as a form of evil. In his struggle against death, Howard fed the stray cats in his barn, taking care to protect them from harm as much as he could. I believe that Howard’s fiction pulsed with a zest for life because he saw death — universal destruction, de Camp called it — as the true enemy of man.

In “Worms of the Earth,” Bran Mak Morn is stirred to hatred by the crucifixion of one of his followers, a hideous death dealt out in a capricious manner by the hated Roman masters. But what Bran ultimately unleashes, the worms who represent universal destruction with no bounds beyond a hunger for annihilation of all life, is far worse than even the Romans. The worms are worse because they are totally detached from human sympathies — which is as good a definition of modern terrorism as any other.

Without getting clinical, I think it is apparent that Howard suffered from depression and mood swings. He was also an artist, and all artists are both sensitive and idealists. Being an idealist makes for frustration because the world is far from perfect. And there is a fine line between sensitivity and anger.

I think what Howard called hatred we would call anger. Many authors are angry. All the authors I know are angry people — myself included. I don’t think Howard hated himself. I think he hated “the cussedness of things” so much that he was overwhelmed by events, including his mother’s death.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: It actually occurred to me several years before 9/11 that “Worms of the Earth” could be viewed as an allegory about terrorism. However, 9/11 did bring home to us that this was something definitely worth mentioning in the new edition of the study.

And yes, Howard could nurse hatred and grudges, but I feel he may have come to realize that at some point you have to back off and let it go. Otherwise, all that bile just poisons and sickens you while the actual object of the hatred just continues to walk around unscathed and oblivious to your scorn.

STEVE TOMPKINS: One thing that sets your book apart from many critical introductions is that it threatens to turn into a polemic at quite a few points. The reader is challenged by opinions like “The arts have been sapped of all vitality by self-aggrandizing dilettantes on one hand and crass commercial concerns on the other,” or in the new version, “Some adults are reluctant to admit that [the fantasy embodied by Conan] is attractive, in deference to liberal notions contemptuous of even a modicum of male audacity or aggression.” And when I read that “abstractions such as universal brotherhood [override] common sense and [become] detrimental to the continued survival and well-being of that society,” or about the fallacy of granting mercy to “the most vicious malefactor,” there’s a not unjustified cordite-whiff of Death Wish or Dirty Harry in the air. Obviously, we can’t talk Howard without dwelling upon civilization and its discontents, and we’ve all been tempted to draft our favorite authors to run for office on occasion; but please share your thoughts on how your own feelings found their way into the book.

MARC CERASINI: What passes for literature today has indeed been sapped of its vitality — so much so that it is dying on the vine. The great literary figures of the past — Dickens, Scott, Hemingway, Faulkner, etc. — all understood the centrality of story in their work. Today the very notion of “story” is eschewed. Putting a story in ones novel is considered pandering, a kind of bourgeoisie conceit not to be taken seriously.

But the truth is that human beings experience story almost from the moment we experience language. As people mature, they learn to live story, breath story — in films, on television, in novels and stories and comic books. Story is the basis of all faith. Story guides and instructs us. Story provides examples for living.

Now the concept of “story” is not some pulp convention created by Hugo Gernsback during the 1920s. Story has had a form and a function and rules that have remained unchanged for thousands of years. Yet today’s literary novelists shun story — at their own peril, as it turns out, and the peril of their readers.

As Tom Wolfe will tell you, the epic panorama of life, of story, has been abandoned by today’s literati, in favor of novels of self-absorbed, near-narcissistic self-absorption. (See Tom Wolfe’s brilliant essay “My Three Stooges” in Hooking Up.) Now it’s one thing for a novelist to ignore the epic parade of life around him — that’s a matter of choice. But it’s almost criminal for an author of any stature to be completely unaware of the literary works by his contemporaries, to the point of pretending they don’t exist.

This was the case when Philip Roth, penned a thoughtful piece in the September 19, 2004 edition of The New York Times about the creation of his newest tome, The Plot Against America. Plot is an alternative history in which isolationist Charles Lindbergh is elected president in 1940 and refuses to go to war against Hitler, thereby insuring the Nazi conquest of Russia and Western Europe, the total extermination of the European Jew, etc.

Yet with such a vast, epic tapestry to paint, Roth takes the predictable, post-modern approach in his novel. I quote: “To tell the story of Lindbergh’s presidency from the point of view of my own family was a spontaneous choice…It also gave me an opportunity to bring my parents back from the grave…At the center of this story is a child, myself at 7, 8 and 9 years of age. The story is narrated by me…”

So in all this vast tapestry, an Orwellian vision of a totalitarian Europe, France, England enslaved, Russia crushed under the jackboot of Nazism, and all Roth can think of writing about is himself and his family!

Roth then goes on to make one of the most absurdly ill-informed comments I have ever read. Again, I quote: “I had no literary models for reimagining the historical past. I was familiar with books that imagined a historical future, notably 1984, but as much as I admire 1984 I didn’t bother to reread it.”

Roth has never heard of a novel that imagines an alternative history of World War II? Okay, let’s forgive Roth for not knowing about the genre examples — you know, the stuff that’s beneath a man of his high-flown talents and abilities. I’m referring to authors like Harry Turtledove, who has made a career out of re-imagining history, specifically World War II. Okay, Roth can also be forgiven for not knowing Brad Linaweaver’s brilliant and quirky 1988 novel Moon of Ice, because that work is also firmly fixed in the genre of science fiction.

Less believable, however, is the notion that Philip Roth never heard of Robert Harris’ 1992 mega-blockbuster Fatherland, which also envisions a Nazi victory, America’s isolation, and a Kennedy — Joe Kennedy — in the White House. I mean, maybe Harris isn’t literature, but he’s close.

And what about Philip K. Dick’s Man in the High Castle? Surely Dick is considered literature nowadays?

In fact, I have on my shelf a literary study by Gavriel D. Rosenfeld called The World Hitler Never Made, which is hundreds of pages long and talks about over one hundred and fifty novels and stories written in the decades after the Second World War up through the last decade — all of which deal with Hitler’s victory, in stories ranging from those of epic scale, to small, intimate tales dealing with one or two characters, or a single incident.

After making this ridiculous literary gaff, Roth goes on to say: “But my talent isn’t for imagining events on the grand scale. I imagined something small, really, small enough to be credible…”

Welcome to the incredible shrinking novel, written by the incredibly shrunken novelist. (For a more thorough evisceration of the emperor’s new literary clothes, I highly recommend A Reader’s Manifesto by B. R. Myers.)

Tragically, this evident decline is not only true of novels. Painting and the plastic arts have also been corrupted.

How can anyone sane compare an obscenity like Andre Serrano’s “Piss Christ” to Michelangelo’s “Pieta — created to echo Western civilization’s faith. The Pieta represents a supreme act of faith fused with will — a will powerful enough to carve a cold piece of marble into a poignant depiction of the human dimension of godly sacrifice. “Piss Christ” is a piece of reactionary drivel churned out solely for shock value — something that is so derivative it could not even exist without the religion and the divine and liturgical art the work seeks to mock.

But hell, what do I know? I am certainly not an art historian. If you’re the sort of person who thinks a crucifix in a vat of urine or an AIDS quilt are examples of grand human achievement, then the arts are very much alive and vibrant in the twenty-first century. For you, but not for me, in the immortal words of Devo. The sheer amount of boys and young men pumped full of drugs like Ritalin because they were “diagnosed” with ADD, ADHD, or any number of supposed conditions that preclude them from sitting at a school desk for eight hours a day listening to boring drivel, should tell you that “male aggression” (a.k.a. manhood) is being dealt with in a Huxleyian manner in twenty-first century America by American parents and teachers.

In our brave new post-modern world, all males will soon be required to take a daily dose of Soma — and vote for Hillary.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: The personal content was partly deliberate and partly subconscious. In the actual writing, we were experimenting to see if we could impart something of Howard’s own style to non-fiction, to see if we could give it more verve, more snap and crackle. Call me crazy, but I think books should be fun to read.

On the other hand, there was definitely some attitude that seeped in. Popular culture wasn’t always accorded the attention it’s beginning to receive. The Starmont book was the work of two young guys who grew up being told everything they like is shit. We toned down some of the more strident notes in the new edition. Young writers do sometimes have an axe to grind, but I never knock them for it. There is so much that wouldn’t get accomplished without the zeal and vigor of youth.

Will Murray slammed us for identifying too much with REH, but I don’t apologize for that, then or now. Yes, we were in Howard’s corner, but sometimes you just have to do things that way. I mean, how sober and balanced was something like “Superman on a Psychotic Bender”? Were we just supposed to let this sort of crap slide? I remember one thing that really stuck in our craw was the whole business about Howard being “paranoid” for taking up boxing and bodybuilding. This is the sort of thing you get from certain academics and critics who have led fairly sheltered lives. Marc and I both come from a small town near Pittsburgh with a certain reputation for toughness. In places like that, if you want to read and write poetry, you’d better be ready to punch people’s lights out.

As for remaining cool and detached from one’s subject matter, there were instances like the ones you mention — Howard’s disdain for civilization, the appeal of the Conan character to men — where we had to choose between tip-toeing around these matters or taking the bull by the horns. In the preface to his Lovecraft biography, S. T. Joshi, who is pretty level-headed, wrote, “Surely we are long past the naive stage of believing that ‘objectivity’ is either possible or desirable in biography. Even the barest recital of facts is affected (in many cases unconsciously) by the biographer’s own biases, prejudices, and philosophical orientation.” This is going to hold true for S. T., Marc and me, and the author of The Ernie Bushmiller Story. To write biography or criticism about a figure that’s of interest only to a select audience is to undertake a labor-intensive project that has little chance of bringing in all that much money. So if you don’t think that your subject is great, then what in the hell are you wasting your time for?

STEVE TOMPKINS: Your comments reminded me of some things I’ve read by Karl Edward Wagner’s good friend John Mayer about what it was like to be passionate about genre fiction in a 1950s high school. As you suggest, now that we’ve reached an era in which academic conferences on Joss Whedon’s Buffy are capacity-crowded and geek culture (a term I dislike) has become a self-refueling engine that drives much of our commerce, it may be difficult for younger readers to imagine The Way Things Used To Be.

Also, the 1987 version of your book was noteworthy for more references to other writers, thinkers, and poets than had been the norm in what was written about Howard. If you don’t mind, please give us a sort of Murderers’ Row of the authors you believe anyone who’s serious about REH should also make a point of reading.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: There was a time not so long ago when reading comic books and science fiction was really going against the grain. Comics were seriously frowned upon by parents and educators. They thought kids would just look at the pictures and not read. Of course, the truth was that comics readers were being exposed to words like “nefarious” and “invulnerable.” Whereas the pablum we were given in school almost seemed like it was designed to make people hate reading forever, and indeed there are any number of adults today who haven’t read a book since high school. Like REH, I “hated school and hate the memory of school.” I’m often troubled by the notion that its true primary purpose is to train people to tell time, follow a schedule, and sit at little desks doing what they’re told. It serves the purposes of “the man” that people read well enough to function adequately and follow orders, but not to enjoy reading enough to take an interest in anything that might prove too stimulating or thought-provoking.

Marc and I both grew up in the midst of a lot of plodding and unimaginative adults. Science fiction was dismissed with a derisive “That couldn’t happen!” You had to defend it with this lame routine about how Jules Verne predicted submarines and so forth, because anything more esoteric would get dismissed with another derisive snort. Just looking back on all this now is really bumming me out. Goddamn stupid motherfuckers.

As to who else Howard readers should look at, the first name that springs to mind is his favorite writer, Jack London. Martin Eden is of special interest because it really slams home how a working class person trying to make a career in the arts is swimming upstream in a river of glue. Martin Eden, London’s fictional alter ego, takes every beating there is and finally triumphs to become a celebrated author, but he’s so embittered by the struggle that he kills himself anyway. Other writers would be Howard’s Weird Tales colleagues, most notably H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and C. L. Moore. Lovecraft learned of Howard’s suicide from Moore. Not even Joshi has been able to find out how she knew of it before anyone else. Just a thought that occurred to me just now: might Moore have married Howard at some point instead of Henry Kuttner if the former had lived?

STEVE TOMPKINS: Do you believe that there is a distinctively American approach to fantasy? And if so, how does REH slot into that approach? Also, if his work is indeed blood-red, white, and blue, does that serve to make him more rather than less appealing to a worldwide readership?

MARC CERASINI: I agree with Don Herron in that I believe Howard was an American proletariat author in the hardboiled vein. Hardboiled fiction, and its film noir counterpart, are purely American inventions now popular all over the world.

In no way does Howard’s fiction resemble the British fantasy which dominated the genre in Howard’s time and still pretty much dominates today. There is no epic quest in Howard’s fiction, beyond the rather perfunctory search for the Heart of Ahriman in Hour of the Dragon. There are no elves or fairies or gnomes or “little people” to be found in Howard, unless one counts the shriveled, degenerate worms of the earth.

Though Howard’s fantasies are set in ancient times, his characters reflect America. Solomon Kane’s Puritanism is the same dour faith that tamed the Northeastern wilderness, that gained a foothold on America’s shores. Kane’s drive for justice in the face of uncivilized darkness reflects America’s singular determination to bring enlightenment to the world through example — and sometimes force.

King Kull seeks the proper role of kingship the way Washington, Jefferson and Franklin wrestled with the conundrum of leadership without a king.

Conan is, among many other things, an outlaw, something of a frontier gunslinger, a Capitalist hustler and a self-reliant loner — all powerful and evocative American archetypes.

Howard’s singularly American values sets him apart from all other authors working in the fantasy vein.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: Howard’s fantasy was a departure from the European tradition, as Don Herron has pointed out, by being tougher, grittier and more “street.” Marc and I called Conan an embodiment of American dreams and values in the sense that he’s a self-assured winner with a healthy appetite for money, sex, and experience. And of course Howard wrote any number of westerns and stories with regional U.S. settings. So yes, REH is very much an American writer. Still, I imagine that the vigor and vividness of his prose would go over very well in places like Japan and Australia. A collection of his Celtic stories could be a really big hit in Ireland.

STEVE TOMPKINS: My own feeling, as someone whose copy of the 1987 version has long since been broken in binding if not in spirit, is that you’ve now made a superb survey even better. That having been said, two of your conclusions continue to trouble me. In the context of discussing “”The Valley of the Worm,” you write “Only the narrow-minded or over-sensitive would take offense at the racial attitudes reflected in this and other stories by Howard.” Please explain why that isn’t an excessively preemptive and peremptory generalization.

MARC CERASINI: “The Valley of the Worm” is very obviously a fantasy, and the outdated racial notions put forth in that story do not trouble me in any way. If one is troubled by such things, I suggest Howard may not be your cup of grog. Try Harry Potter. Or Eragon. There are no non-politically correct opinions to be found in either series.

STEVE TOMPKINS: There often seem to be as many different views of Howard’s race-based attitudes as there are Howard fans. After your look at “Black Canaan,” you’ve added a discussion of Howard’s black characters and an acquittal on the charge of bigotry. By contending “Howard was by no means a virulent racist by the standards of the day. There is no evidence that he harbored any sort of active hostility towards blacks or other minority groups,” haven’t you left quite a hostage to fortune pending the eventual dissemination of something like “The Last White Man,” or the really virulent fulminations where Howard was reacting to the Massie case or venting in (often unpublished) letters?

MARC CERASINI: That’s a real “do you still beat your wife” kind of question, and my gut response would be, why ask if Howard was a closet racist? Is Alice Walker anti-male? Is Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials anti-Christian? Is E. L. Doctorow anti-American? Is Philip Roth anti-gentile? Were Lewis Carroll and J. M. Barrie closet pedophiles?

So what if they were, or are? Should we dismiss these authors out of hand because we may not agree with all of their opinions, or because they had some quirky opinions, or even twisted sexual kinks?

In these oversensitive times, one could find elements of racism and sexism in Howard’s works. And in Jack London’s and Mark Twain’s too. And how about that fellow Jean Raspail? Should we reject the prophetic author of The Camp of the Saints because he harbored decidedly un-politically correct thoughts about African immigrants (and was hammered for them when his novel appeared) even though the conflagration Raspail warned against is currently engulfing France?

I maintain that Howard was less prejudiced than the average man of his day, of his class and environment. Despite marginally offensive passages found in “The Black Stranger” and elsewhere, Howard also created a number of sympathetic, wise, even superior African characters (Remember N’Longa?).

And I’ll bet the “virulent fulminations” of Howard’s unpublished letters and his “The Last White Man” pale in comparison to H. P. Lovecraft’s railings against the “mongrel hordes” of “apelike Negroes” and “rat-faced Semites” that “infested the streets of New York City.” And wasn’t it H. P. Lovecraft who wrote the poem “On the Creation of Niggers?”

Now before I get e-mails and letters from Lovecraftians, let me make one thing clear. I am not attacking Lovecraft. He’s one of my favorite authors, a genius whose works are celebrated all over the world and rightly so. All I’m asking is should we all turn our collective backs on Lovecraft, universally reject all of his work, his legacy, because Lovecraft wrote a racist poem or had a racist thought?

CHARLES HOFFMAN: I guess we must not be explaining this clearly enough. It’s all a matter of context. Yeah sure, REH would be considered a racist by today’s standards, but then, so could just about anybody who died before 1960. Abraham Lincoln was a racist by today’s standards — maybe not the Abe Lincoln on the penny, but the real guy for sure. You can look this stuff up. As for Howard, that’s why we use those qualifying clauses like “By the standards of the day” and “For a Southerner who died in 1936.”

Exactly when did he write stuff like “The Last White Man” and “The Fear Master”? Fairly early on, I would imagine. Some of this shows the influence of Jack London, who sounded the alarm about the “Yellow Peril.” London, however, is redeemed in the eyes of left-leaning intellectuals by the fact that he was a Marxist. Howard would have inherited his share of prejudice, but I think he may have mellowed as he grew older and had to sort out the feelings of erotic attraction he harbored towards black women — and don’t tell me the hotter passages about Nakari in “The Moon of Skulls” aren’t pure jerk-off fantasy. He would have had to wrestle with questions about how big a deal race is after all. This would have lead him to stuff like “The Dead Remember” and Ace Jessel. I believe we described his handling of the latter as being “sympathetic, albeit condescending.” But try going back in time to circa 1935 and finding another white man within a hundred-mile radius of Cross Plains who showed as much empathy to blacks and Indians as REH did. On the other hand, this doesn’t mean he never made harsh remarks about them. People are not consistent in their attitudes. You have to allow for a certain amount of ambiguity as well. Another thing you have to keep in mind is that no one in 1935 would have known what the hell a “racist” was.

Unfortunately for Howard, and to a greater extent Lovecraft, racism is the one thing most thoroughly condemned in today’s society. His reputation could never be so threatened by charges that he was a drunkard or doper or whatever. To make matters worse, people are so incredibly thin-skinned about this nowadays. One need only step a little out of line to be labeled a racist or homophobe or whatever, and in my opinion this can only lead to ill feeling worse than that which originally existed. You couldn’t make Blazing Saddles now. I saw this several times in 1974 as part of fairly integrated audiences, and everyone loved it. Less than twenty years after the start of the civil rights movement, and it was like “We’re so cool we can laugh at this shit.” But not today, I’d wager. I guess it’s a matter of “two steps forward, one step back.” Or else, a matter of crabby people getting their way. Nowadays, everyone has such a big axe to grind.

And that’s the problem as far as REH is concerned. Rusty Burke may think it’s okay to matter-of-factly state “Robert Howard was a racist” and move on in his essay about Howard’s “piney woods” stories. The only trouble is, with the word “racist,” people hear it and immediately think the worst. We’re talking fangs and cloven hoofs here. Like REH was running around lynching blacks with a maniacal gleam in his eye and evil laughter erupting from his throat. So if you simply “admit” that “Howard was a racist,” you are really just handing some pipsqueak, who may already feel threatened by all the so-called “macho” stuff in Howard’s work, something big to harp on. That’s why we felt the need to place all this in some sort of context.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Of course you had all manner of Procustean choices to make, but you include no discussion of the individual El Borak stories, not even “Hawk of the Hills,” “Son of the White Wolf,” or “The Lost Valley of Iskander.” Was this simply the tyranny of page count at work, or do you find Francis Xavier Gordon to be a comparatively less resonant or multidimensional character than the fantasy heroes?

MARC CERASINI: I don’t find these tales particularly entertaining nor important. The fantasy element is marginal, and I don’t find the settings at all convincing. While I’m no stickler for the facts, in the case of these stories Howard would have been better served if he’d done a little bit more research, and thought about his characters and motivations a little bit more.

As it stands, Howard attempted to mimic the career of T. E. Lawrence without exploring the dark side of a civilized man “going native,” which is surprising because Howard seldom eschewed exploring his characters’ dark side. Probably this is due to the fact that Lawrence of Arabia’s exploits and career had yet to be thoroughly examined and dissected when Howard wrote these tales. He was still considered a hero, a British adventurer. The deconstruction of Lawrence’s life and reputation would not come until much later. Yet it is still disappointing because Howard wrote convincingly about the way native philosophy can get under the skin and corrupt a civilized man’s soul in the Solomon Kane tales, and in “Black Canaan,” so this omission in the El Borak tales is all the more glaring.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: We did try to give the El Borak stories their due by pointing out that they were written at the same time as the Conan stories, when Howard was at the top of his game. Yes, we do discuss them collectively rather than individually. At the time we were doing the original Starmont book, we didn’t have much more to say about them. Of course, a lot has recently been written about them by others, since these stories of intrigue in the Middle East are very timely. Right now, I would just like to add that Francis Gordon seems a very different character from Kirby O’Donnell, despite superficial similarities. Though steeped in Eastern ways, Gordon never goes completely native, as O’Donnell does. Gordon is the ultimate Western interloper. Mention is made of his past as a gunfighter from El Paso, and his grandfather’s exploits as an Indian fighter — you can’t get more “West” than that. And in one story, Gordon just walks into a camp of natives and starts telling everyone how to do everything. Kirby O’Donnell is a character I wish REH had written more stories about, but it seems like he could only come up with that one “treasure hunter” plot device.

STEVE TOMPKINS: You write “Howard wisely decided against actually setting any of the Conan stories in Cimmeria; it is occasionally mentioned, but never presented to us,” and that adverb “wisely” interests me. De Camp and Carter never trespassed in the land of darkness and deep night, but from the Eighties onward John Maddox Roberts, an initially reluctant Roy Thomas, Loren Coleman, and Kurt Busiek have all set pastiches there. Does piercing the Cimmerian mists always puncture the Cimmerian mystique? We do stop in at Atlantis at the start of the Kull series; do you think the role of Kull’s home island is different than that of Cimmeria in the Conan stories?

MARC CERASINI: One need only read a few pages of the first of the new Age of Conan novels from Ace, or read the issues of the Dark Horse Conan comic set in Cimmeria, to witness this demystification first hand.

I don’t know about you, but I prefer to envision Cimmeria in poetic, metaphorical terms — godlike men striding the earth, wielding massive iron swords as if they were giants. I don’t want to see a cast of fur-wrapped Young Adult characters who think, talk, and act like a role-playing gaming clique minus the dice. Or even worse, Conan versus the schoolyard bully, as we saw in a recent Dark Horse comic.

That said, demystification of Conan and Cimmeria may be unavoidable. John Milius (an otherwise fine filmmaker) made Conan the Barbarian as Conan versus the California Lifestyle and we saw the result.

Even worse, Dark Horse just offered a comic where King Conan wanders to Khitai and battled a killer turtle! You can almost hear the story conference now. “Well, Khitai is kind of like Japan so let’s put samurai in it.” This train of “thought” somehow led to an attack by a Hyborian Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle.

Suddenly we’re back to the bad old days at Marvel again.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: The very name Cimmeria is evocative and mysterious. Most people are unfamiliar with the name, and most of those who do know it in connection with Conan. The poem “Cimmeria” was written after the bulk of Howard’s other poetry, and could be among the very last poems, other than story headings, that he wrote. It is a remarkably effective venture into blank verse; I don’t recall REH doing any others. And Conan’s own recollections in “Phoenix” are almost as spare as haiku — skies nearly always gray, wind moaning drearily down the valleys. In both cases, we have something like a magic spell being chanted. It all goes to convey a sense of beyondness. Cimmeria is beyond the pale of civilization, beyond the last frontier.

Of course pastiche writers are going to explore Cimmeria. That’s what pastiches are for. They’re a separate thing from the canon, so you can satisfy your curiosity without it reflecting on the original effect Howard was going for. Also, Roy Thomas was doing the monthly Conan comic, plus Savage Sword, and both ran for a good many years, so it only makes sense that he fill in all the nooks and crannies. I remember one that took place in the Border Kingdom.

Atlantis is a whole different story. Atlantis, unlike Cimmeria, is a name that everyone and his brother does know. And the image they invariably have is of this super-civilization, in some cases the very fountainhead of all science and culture. Howard was really out to rock the boat by portraying Atlantis as a primitive, sparsely settled land roamed by barbaric tribesmen. Therefore he had to go into some detailed description and even set some action there in order to convey his non-conformist vision of the Lost Continent.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Chuck, in 2005 you contributed a thought-provoking overview of Howard’s spicies to The Cimmerian. Is there still an aspect of Howard’s creativity, even after the upsurge in activity that’s been going on of late, that either of you would consider to be under-appreciated or neglected?

MARC CERASINI: I think Howard’s comedies have been neglected, and they are most surely under-appreciated. But creating an academic study of Howard’s comedy is somehow regarded as less sexy than his fantasy creations, so it hasn’t happened and probably won’t any time soon.

CHARLES HOFFMAN: I don’t know. Sometimes, some new insight concerning an individual story will occur to me upon re-reading. For instance, it recently struck me that “The People of the Black Coast” may be the most Lovecraftian of any Howard story. Note that that is “Lovecraftian,” not “Cthulhoid.” No Von Juntz, no “Nameless Cults.” But here we have humanity taken down a peg by the discovery of a mentally more advanced species, evolved along non-mammalian lines, that regards human beings as of no more interest than any other lab specimens.

STEVE TOMPKINS: Howard created two unforgettable usurpers, and there have been a host of pretenders to his own throne. Which writers would you consider his true-born heirs in modern heroic fantasy? To put it another way, if you could do another Starmont Guide or critical introduction, to whom would it be devoted?

CHARLES HOFFMAN: As to who’s hot stuff in heroic fantasy today, I couldn’t answer that because (gulp!) I haven’t read any! I read Thongor, Brak and Elric in the Seventies, but nothing but Howard since. I suppose someone could write a good book about Jane Gaskell’s work — I would like to re-read that at some point. As to whom I would like to write about, there are two individuals I’ve written about that I would like to treat at greater length. The first is James Clavell. When he died, I really felt like I had lost a grandfather. If you want to understand how the world works, read James Clavell. The other is Bruce Lee, whom I consider one of the most remarkable men of the twentieth century.

MARC CERASINI: As I’ve stated above, I don’t regard Howard as exclusively a fantasist, so I really can’t name his true-born heroic fantasy heir — especially since in my view the genre has become pretty predictable. I’ve read pretty much everything Howard ever wrote and I can’t find a traditional elf, gnome, fairy, sprite, epic quest, or leprechaun anywhere. Therefore, I believe something like Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, James Ellroy’s American Tabloid, or James Clavell’s Shogun, Tai-pan and King Rat are closer to the vein in which Howard was writing, yet these authors and works are not precise matches, either.

So who else could I pick?

Fritz Leiber wrote excellent fantasies, but I don’t count the Grey Mouser tales among them. I enjoyed the Brak the Barbarian stories, but felt John Jakes hit his stride with his historical novels. Moorcock’s Elric is a fascinating character — very Clark Ashton Smith. But Elric springs from the British tradition, complete with a magical sword, a la King Arthur, so he hardly counts.

Should I choose the ecologically-sensitive, anti-war fantasies of David Gemmell? No way.

How about the Dark Elf tales of R. A. Salvatore?

The epic quest fantasy of Richard Jordan?

Gormless, derivative drivel like Eragon and Eldest?

Do any of those authors remind you of the magnificent and sublime stories of Robert E. Howard?

I don’t think so.