The Conscience, and the Kisses, of a King

Saturday, January 24, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

. . .the house of life was riven asunder and the human trinity dissolved, and the worm which never dies, that which lies sleeping within us all, was made tangible and an external thing, and clothed with a garment of flesh.

Arthur Machen, The Three Impostors

Within the overall gift-that-keeps-on-giving jamboree of The Collected Letters of Robert E. Howard, for those of us who consider “Worms of the Earth” the greatest story this great writer ever told, a comment in a November 1932 letter to Tevis Clyde Smith is more precious than mithril or orichalchum: “The readers took well to my ‘Worms of the Earth’ story. I didn’t know how they’d like the copulation touch.”

I’m beyond baffled that not one of the few Howardists who had access to all-or-most of his letters has ever quoted this; we have so little on the subject of “Worms” from its author, really just the mea culpa to H. P. Lovecraft about having misspelled (or Celticized) “Eboracum” as “Ebbracum” and the well-known, Howard-as-his-own-best-critic insight that “Worms” was the only time he looked through Pictish eyes and spoke with a Pictish tongue. Much more is going on in his “copulation touch,” the night Bran Mak Morn spends with Atla the witch-woman, than Romanophobic politics making for strange bedfellows. The sex isn’t just sex; it’s transgressive sex; Howard’s hero demeans himself en route to damning himself.

The episode crackles with tension, the tension between what Howard allowed himself to say, or was allowed to say by his sense of (Farnsworth) Wright and wrong, and what Atla (an aspect of Howard himself) wanted him to say, the tension between the Thirties and our own time, the tension between viewing Atla and Bran through an American Studies prism or a history-of-weird-fiction prism, the tension between soft-bigotry-of-low expectations as to what a sword-and-sorcery story should be and what “Worms” actually is. It’s our good fortune that all such tensions add up to a creative tension that make this masterpiece sit up straighter on its throne and reign if anything even more more regally. As per Richard Slotkin in Regeneration Through Violence, popular literature often “replaces the troublesome and problematic facts of the real world with a counterworld of pseudofacts,” whereas the powers, and ambitions, of an artist “enable him to see further into his material and extract more from it in the way of moral, social, and metaphysical meaning.” Witness “Worms,” which, as Don Herron long ago pointed out with his distinctive precision and concision, casts “an ironic light” on the “entire body of Howard’s fiction.”

To keep this from being as long as William Henry Harrison’s Inaugural, we’ll join the story already in progress, as Bran rides past fen-men who speak “a strange mixed tongue whose long-blended elements had forgotten their pristine separate sources.” Very soon such words are going to be made flesh, mingled flesh. The king, we’re told, scorns the fen-dwellers as “men of mixed strains,” for “the chiefs of Bran’s folk had kept their blood from foreign taint since the beginnings of time” (Here we must set aside our reservations about endogamy and accept that we’re in Howard’s fantasy). Keep that phrase “foreign taint” in mind; pride goeth before a fall into a taint that will redefine foreignness.

Bran continues westward (to go west can mean to go deathward), “blackly etched against the dim crimson fire of the sunset” — foreboding colors, and (coincidentally?) the two that haunt American mythology. Howard likens him to “the last man on the day after the end of the world,” and a world, the marginalization-reversing, culture-uplifting world aspired to in “Men of the Shadows” and sustained in “Kings of the Night,” will end during the course of the story. If in some ways a last man is little different from a first man, the Pictish Adam is about to meet his Lilith:

The woman was not old, yet the evil wisdom of ages was in her eyes; her garments were ragged and scanty, her black locks tangled and unkempt, lending her an aspect of wildness well in keeping with her grim surroundings. Her red lips laughed, but there was no mirth in her laughter, only a hint of mockery, and under the lips her teeth showed, sharp and pointed like fangs.

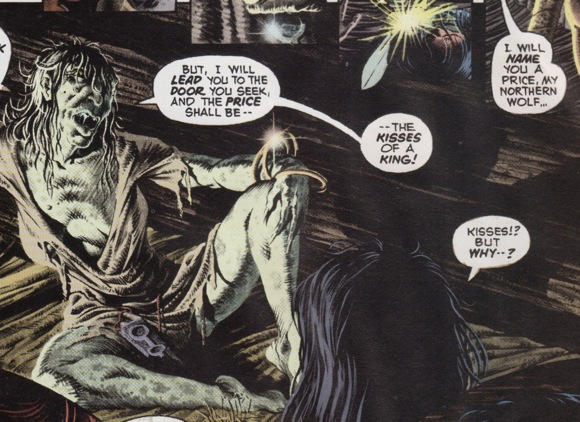

One purpose of fangs, of course, is to inject venom, which brings us to the Atla-question: scaly-sexy (preserving the old, old association of the serpent with temptation) or more suitable for a ka nama kaa lajerama-ing? Fred Blosser’s “Bran Mak Morn. . .Destroyer” in the Wandering Star/Cross Plains Comics’ Worms of the Earth (one of Jim Keegan’s many finest hours) memorably describes Tim Conrad’s Atla as “a gaunt, bony-chested, stringy-haired harpy who somewhat favors the Old Witch from EC Comics’ venerable Haunt of Fear. ”

Gary Gianni’s Atla in Bran Mak Morn: The Last King could be the weirder sister of the Conrad version, and Fred’s caveat could apply to both:

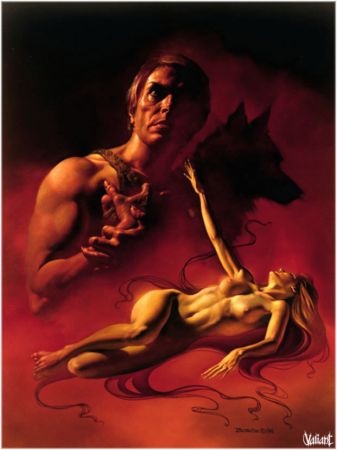

. . .Howard’s description implies that Atla projects some measure of slatternly allure, for all that Bran feels “an involuntary shudder” when he touches her. Echoes of this appear in the sinister tryst between Schwarzenegger’s Conan and the slinky witch played by Cassandra Gaviola in the movie Conan the Barbarian, a scene surely inspired by the fateful meeting of Bran and Atla in “Worms.” For obvious reasons, Bran doesn’t respond as eagerly to Atla as Conan does to Gaviola’s femme fatale, nevertheless, the sexual current is undeniable.

(Those who’ve brought themselves to read or read about the King Conan: Crown of Iron screenplay will recall that John Milius continued his smash-and-grabs on “Worms” with the ersatz-Pict “Orlock Mak Morn” –please kill me forthwith)

Fred generously makes the case that “through visual shorthand, the artists make it impossible for the reader to see [Atla} as anything other than alien. The horror of Bran’s sexual compromise, thusly, is magnified.” Which is where I part company with him; comics often aren’t in the business of selling subtlety, but for me much of the horror of the bargaining-and-bedding is vitiated if Atla is a freakshow from the get-go.

When she taunts Bran at one point, her laughter is “like sweet and deadly venom,” and my preferred visualization would capture the sweetness as well as the deadly part. I might even upgrade Fred’s “measure of slatternly allure” to disturbing beauty; amidst the murk and mire of “Worms,” Howard supplies a coldly beautiful visual in Chapter V, as the starlight dims by comparison to “the glitter in the eyes of the woman [gliding] beside the king.” Atla’s tragedy — and “Worms” makes room for her tragedy as well as Bran’s — is that she can’t quite pass, to use a simple, single-syllable American idiom that contains generations of misery. The king’s loathing, that shudder he can’t suppress, should come from what he senses about her, not what he sees straightaway.

She identifies herself as “the witch-woman of Dagon-moor,” and her living conditions suggest deprivation as well as privacy: a broken bench, a scanty meal, a squalid hearth. Bran notes “her lithe, almost serpentine motions, the ears which [are] almost pointed, the yellow eyes which [slant] curiously.” Inside the hut, when Atla turns to him it is with “a supple twist of her whole body”; supple is usually a hot-to-trot adjective for Howard. Plus her first reaction when Bran broaches the Worms suggests that the witch and the were-woman are in abeyance for the nonce; she breaks a jar and stammers.

The king dismisses her pretense of ignorance: “By the mottles on your skin, by the slanting of your eyes, by the taint in your veins, I speak with full knowledge and meaning.” This is perhaps unwise of him –full knowledge in the biblical sense is yet to come. Note the recurrence of the taint concept, and also the threefold “by the. . .” repetition, which echoes Bran’s earlier “By the thorn in the foot, the adder in the path, the venom in the cup, the dagger in the dark” vengeance-vow. In their “Robert E. Howard, Bran Mak Morn and the Picts” essay, Rusty Burke and Patrice Louinet trace Howard’s poem “The Song of a Mad Minstrel” to Kipling’s “A Pict’s Song” in Puck of Pook’s Hill. In which case Bran’s aforementioned vow is also part of the same line of descent: thorns pierce feet in all three. But my literary ectoplasm-detector doesn’t stop there. The most ingrained “By the..”-construction for the literate English speaker is that in Act IV, scene 1 of Macbeth: By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes. And something wicked is indeed on the way here (Me, I believe there’s more of the Witch of Endor than the Scottish play’s witches in Atla, though).

Atla informs Bran that he has in fact heard naught but a bird singing, an appeal to an upper world both natural and comparatively rational, but he corrects her: not birdsong but the hissing of a viper has reached him. “I come seeking a link between two worlds; I have found it.” He has in fact found not just the link between, but the legacy of, two worlds; and it is the Pict who proceeds to place miscegenation on the conversational table: “. . .they still steal forth in the night to grip women straying on the moors,” he reminds Atla, in effect citing her “slanted eyes” as evidence.

He tries her, unsuccessfully, with blade and bribe: “What is this rusty metal to me?” she says of the coins he displays. The rejection of wealth — earlier in the story Bran himself regards gold as “so much dust, flowing through his fingers,” and essentially useless in Pictdom — is a sword that cuts both ways. Next, he offers “the head of an enemy,” revenge on her behalf as the price of, and precursor to, his own revenge. She’s ready for him: “By the blood in my veins, with its heritage of ancient hate, who is mine enemy but thee?” A Macbethian echo again, coupled with a verbal intimacy foreshadowing the physical intimacy to follow.

When Atla’s dagger proves to be her least lethal weapon, Bran casts her aside with “a loathing flirt of his wrist.” The oxymoron is brilliant; a loathsome flirtation is exactly what’s been going on, and he doesn’t toss her just anywhere, but “across her grass-strewn bunk.” (Grass as a natural veneer for an unnatural act?) Atla laughs up at him — Invitingly? Excitingly? — and having bared her teeth, she will next bare her soul — oh yes, she owns one, as becomes clear when she narrows the distance between hostess and guest, physical, racial, and moral: “I will lead you to the doors of Hell if you wish –and the price shall be the kisses of a king!” And once again a central text of the Western imagination looms up behind Howard’s characters by way of “the doors of Hell”: Virgil’s facilis descensus Averno; noctes atque dies patet atri ianua Ditis, rendered by John Dryden in 1697 as

The gates of hell are open night and day;

Smooth the descent, and easy is the way.

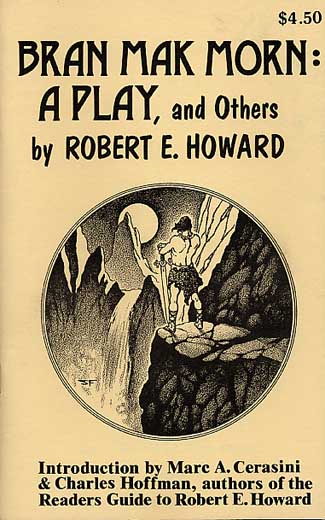

Without meaning to slight its non-verbal interludes, “Worms” is utterly propelled by utterances. Although far from talky, the story is speech-centric — consider for a moment the king’s threat-cascade that sprays and stays his immemorial enemies inside Dagon’s Barrow — with Howard’s reference to having spoken with a Pictish tongue all the more arresting accordingly. Words illuminate actions in some very dark places; in fact, one way of looking at “Worms” is as the true Bran Mak Morn: A Play. The story can be broken down into — and could be adapted for the stage as — the following exchanges:

1. Sulla/Bran

2. Bran/Grom

3. Gonar/Bran

4. Atla/Bran

5. Bran/Worms (with Atla as their mouthpiece)

6. Legionary/Bran

7. Bran/Atla

Atla’s half of Number 4 culminates in one of Howard’s most revelatory speeches, a passage that showcases the extent to which poet and pulp pro are co-pilots in his finest work. An audiobook of “Worms” would have to be performed, not just read aloud, with Kevlar-piercing thespian firepower. Were-woman does not rule out “Ware, woman!”

“What of my blasted and bitter life, I whom mortal men loathe and fear? I have not known the love of men, the clasp of a strong arm, the sting of human kisses, I, Atla, the were-woman of the moors! What have I known but the lone winds of the fens, the dreary fire of cold sunsets, the whispering of the marsh-grasses? — the faces that blink up at me in the waters of the meres; the footpad of night-things in the gloom, the glimmer of red eyes, the grisly murmur of nameless beings in the night!

“I am half human, at least! Have I not known sorrow and yearning and crying wistfulness, and the drear ache of loneliness! Give to me, king — give me your fierce kisses and your hurtful barbarian’s embrace. Then in the long years to come I shall not utterly eat out my heart in vain envy of the white-bosomed women of men; for I shall have a memory few of them can boast — the kisses of a king! One night of love, O king, and I will guide you to the gates of Hell!”

Which is to say, to the gates of a realm that hath no fury, but also no desire, like that of a woman heretofore scorned. As a cheerless conflagration, Atla’s “dreary fire of cold sunsets” surpasses the “dim crimson fire of the sunset” and “desolate crimson of the sunset’s afterglow” we find elsewhere in the story: throughout “Worms,” the light always fails or flinches, and hate affords the only heat.

Her speech is an exceptionally rich text; the white-bosomed women are a callback to Bran’s divertissements while ambassadoring in Eboracum, and the fens where Atla lairs are of course Grendel-country. By conjuring night-thing footpads, red glimmers, and grisly murmurs, the witch all but ushers that renowned shadow-stalker onstage (and is the monster of Dagon’s Mere a Nessie-type creature or a river-hag or “water-carline” like Peg Powler, Jenny Greenteeth, or Mama Grendel?) In his essay “Grendel: Bordering the Human,” Philip Cardew characterizes Beowulf’s foeman as “a liminal being, a being of margins and peripheries, poised between two worlds.” So’s Atla (amusingly, one of the Anglo-Saxon poem’s Grendel-terms, heorowearh hetelic, hateful blood-wolf, works better for Bran himself). Time and chance have even interpolated an allusion Howard can’t possibly have intended — who now can read of “the faces that blink up at me in the meres” and not think of Tolkien’s Dead Marshes?

Most of this is an imagery-expansion from the story’s early draft, and thank the Moon-god for late-arriving inspiration, because Atla’s human attributes can only drop from her “like a cloak in the night” if the story has established those attributes. What Bran is about to have to live with is horrible, but so is the life the witch has lived. Skirting indelicacy, we might say that where Bran only reluctantly enters Atla, Howard has entered into her first and far more fundamentally. He not only suffered his witch to live, but suffered with her. The ecosystem of Atla’s isolation is short on post oaks and sand roughs, yet we intuit that her creator knows this emotional terrain like the back of the hand he sometimes felt he’d received from his community.

As Chapter IV begins we rejoin the erstwhile bargainers on the morning after; dawn’s “cold gray mists” enshroud Bran “like a clammy cloak,” a reminder of the enfolding clamminess of the night just passed. “Make good your part of the contract,” he demands, seeking refuge in the legally, rather than emotionally, binding. Atla’s “red lips [smile] terribly”; she has ties that bind on her mind, too. She invokes the cutting of the thread that “bound Them to human life,” and emphasizes the neolithic apartheid Bran’s ancestors enforced: “Far, far apart have they grown.”

If we read on in a Viennese accent, the king’s penetration of Dagon’s Barrow, “a round hillock overgrown with rank grass of a curious fungoid appearance” jumps out at us. Likewise “the foul charnel-house scent,” his fear of “a fall into unknown and unlighted depths,” and the fact that the stone of the passageway is “slimy to the touch, like a serpent’s lair.” Maybe Farnsworth Wright was distracted by one of Seabury Quinn’s whiphanded workouts the same day as “Worms” crossed his desk.

In the finished story, a new and iron-fingered paragraph precedes Atla’s insistence that the Black Stone be restored to the Worms. For Bran, the ignorance of Caesar’s invaders has begun to seem like bliss: “Well for the Romans that they know not the secrets of this accursed land!” he bellows. But Atla has identified the chink in his armor, as she could not when plying her dagger: “Are they [all the horrors he’s just listed] more foul than a mortal who seeks their aid?”

At the climax, Atla’s “You blench at a little thing. . .” in the early draft is drama-boosted through reconfiguration as a question: “Do you blench at so small a thing?” And whereas in the draft, she merely shrieks with fearful laughter, in the published “Worms” she does so while shedding “all human attributes. . .like a cloak in the night.” The simile caps much previous imagery; the story billows with cloaks metaphorical and mundane. Atla loses her human attributes after Bran regains his humane attributes, and the cumulative impact of serial cloakings and uncloakings is darkly epiphanic — of course the attributes in question fall away like a cloak in the night; how could they not? After that, we take leave of Bran as “a hunted ghost,” and of Atla as a sound effect, the “hellish laughter of the howling were-woman.” Snakes don’t howl; at the end, the character is as lupine as she is ophidian.

Had “Worms” been written by a British fantasist, we could stop right about here, celebrating Howard for rendering explicit (by Thirties standards) the implicit sexual dread of the Machen-devised Black Seal/Little People story-cycle. A human intensifier, our reason for blogging never leaves a trope or motif more pallid, perfunctory, or half-hearted than it was when he found it, and all around his “copulation touch” there swarm the ghosts of fairest flowers dragged underground by troglodytes, from Persephone in the grip of Hades through Machen and post-Morlockian tunnelers like those of Richard Laymon’s The Cellar and Neil Marshall’s The Descent. But we’re dealing with an American, and a Southwesterner at that, so other shades, those of concepts like squaw and halfbreed and mulatto, also circle Atla’s hut.

Upon publication in TC V4n3 (June 2007), David Hardy’s “Worms of the Frontier” became required reading for Howardists of a vermicular persuasion. He writes “Bran does what he must to get his revenge, but his situation has linked him with deep fears of American racial identity.” The deepest such fear is miscegenation, during which the Otherness of the Other is put to the test, and the reason why a borderline-enticing Atla is so important to me is that Bran commits miscegenation, not the teratophilia the Atla of Tim Conrad or Gary Gianni would entail.

Miscegenation is a word that, like the Gettysburg Address, was a product of the Civil War year of 1863, having been coined for a Lincoln-baiting, button-pushing pamphlet written by two Democratic hacks. An unappealingly freighted, reassuringly dated term that has almost nothing to do with anything we see happening all around us today, but one required for any serious discussion of two of Howard’s greatest stories, “Worms of the Earth” and “Black Canaan.” To engage with such stories we must resummon the hysteria about “mongrelization” that during the low points of the HPL/REH correspondence makes them come across like the two all-time least attractive members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, shrieking about mud being tracked onto Mount Vernon’s cherry-tree hardwood floors.

As it happens Howard explained his sliding scale for miscegenation in “Marchers of Valhalla”:

A man is no better and no worse than his feelings regarding the women of his blood, which is the true and only test of racial consciousness. A man will take to himself the stranger woman, and sit down at meat with the stranger man, and feel no twinge of race-consciousness. It is only when he sees the alien man in possession of, or intent upon, a woman of his blood, that he realizes the difference in race and strain.

At this late date a shorter translation might read, What’s mine is mine, what’s yours is negotiable. “Home games” are out of the question; Howard’s inflexibility on this point is virulently demonstrated by his ravings about the Massie case, during which all of the skepticism about institutions and authorities so evident in the Conan series deserted him, as did, his Bible Belt upbringing notwithstanding, the story of Potiphar’s wife. We catch him speculating to HPL in May 1932 about how different, and doubtless miscegenation-minded, inferiors would smell while roasting, and he even anticipates Pearl Harbor by wishing he could lead “a squadron of bombing-planes” against Hawaii. That kind of posturing rules out perspective, complexity, and creativity, so no home games leaves us with, well, away games. Both “Worms of the Earth” and “Black Canaan” are away games, white man and woman of color, or in Atla’s case woman-of-color-fantastication.

These stories (“Wolves Beyond the Border,” featuring Kwarada the witch, might have been another) are compelling in part because race war and the war between the sexes are being waged simultaneously. “Black Canaan” provides the inflammation without the consummation; “Worms” provides the consummation without the inflammation. The Kirby Buckner story is the more hot-blooded, the Bran story, cold-blooded, and not just because of Atla’s parentage.

Buckner really doth protest too much: “I had confronted sorcery beyond my power to resist. I had felt my will mastered by the mesmerism in a brown woman’s eyes.” One need know little about the Reconstruction-era South to grasp the provocation of that verb “mastered.” He also confides “I could not deny the incredible magnetism of this brown enchantress,” and it is easy to suspect that the Bride of Damballah’s juju is a fig leaf, that the story’s soundtrack should embrace anachronism and be “Brown Sugar.” Arguably more honest is his admission, “All the black rivers of Africa were surging and foaming within my consciousness, roaring into a torrent that was sweeping me down to engulf me in an ocean of doom.”

Back in 2004, when the honor of working on The Black Stranger and Other American Tales was mine, I wrote “Sinuous and insinuating, the Bride of Damballah is both the result of, and an incitement to, miscegenation, the true forbidden fruit of the American Eden.” If we accept that her real intention is not to seduce, but to sacrifice Buckner, it is Atla who looks to repeat her family history; the coerced sex that yielded her is the preamble to the coaxed sex to which Bran yields. The half-human witch gets her man where the half-white Bride does not, a carnal example of the “liberation of imagination” that Richard Matthews sees as fantasy’s mission statement.

While describing Bran’s “black eyes, black hair and dark skin to HPL in January 1932, Howard noted “This was not my own type; I was blond and rather above medium size than below. Most of my friends were of the same mold. Pronounced brunet types such as this were mainly represented by Mexicans and Indians, whom I disliked. ” By March of that same year he was admitting that Lovecraft was right to compare his Pict-affinity to “the Eastern boy’s Indian-complex.” In “Worms,” Howard teleports Natty Bumppo’s nervously-brandished “man without a cross” status as the bearer of “white gifts” to a more ancient frontier: if the Picts are Indians, we meet the Indians’ Indians, the aborigines they displaced and disinherited, as we also do in the actual Southwestern setting of “The Valley of the Lost.” But that story lacks liminality, lacks Atla. Previously a “man without a cross,” Bran becomes a man double-crossed, a dark-eyed Pict who “lowers” himself to coitus with a species-straddling witch.

Unlike Don Herron, I’m an admirer of Karl Edward Wagner’s Legion from the Shadows, but in a different, more perverse sequel to the story, Bran might have found no sexual healing in the arms of “purely” Pictish or Celtic women —supposing Atla were his best, rather than his worst experience? Once you’ve gone snakey, all else is just fakey. Actually, having absorbed the story of Arthur and his sister Morgause years before I read “Worms,” my fealty has always been to an even darker outcome, the sinister signposts to which would be Atla’s “stay and let me show you the real fruits of the pits” and “in their own time, they will come to you again!” In nine months’ time? Could the tidings we receive long centuries later in “The Dark Man” from Brogar, that “Bran Mak Morn fell in battle; the nation fell apart,” involve not just renewed Roman aggression but the Mordred of a Caledonian Camlann? Posit a careworn Bran, with no trueborn heirs, and the arrival at Baal-dor of a son with the ability to, yes, cloak himself in human attributes. . .What other “real fruit” would so bear out the witch’s But you are stained with the taint taunt?

For me, despite the shrugs of his apologists, nothing so discredits L. Sprague de Camp’s Dark Valley Destiny as his failure, in a frickin’ critical biography, to mention “Worms of the Earth” even once. He was absolutely wrong to have ignored the story, which David Hardy is absolutely right in classifying as a frontier story. The frontier of what Bran will endure to enact his revenge, the frontier of what we the readers are willing to deem human, muster sympathy for and empathy with, the frontier of the territory the sword-and-sorcery subgenre can claim. How far into the “dim fens of the west” are we willing to venture?