What a Mummer Wild, What an Insane Child

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Mark’s post about the new Batman film from a Howardist’s perspective was one of the better contributions to the long Dark Knight of the soul that’s fallen on the blogosphere, arguably a wee bit more plausible than the following Andrew Klavan assertion in The Wall Street Journal: “There seems to me no question that the Batman film The Dark Knight, currently breaking every box office record in history, is at some level a paean of praise to the fortitude and moral courage that has been shown by George W. Bush in this time of terror and war. Like W, Batman is vilified and despised for confronting terrorists in the only terms they understand.” Artist Drew Friedman begs to differ. And Cheney, the No. 2 who tries harder? Is he maybe Harvey Dent? Or remember the online debates when 300 was released? Was Bush Leonidas, or was he Xerxes? And who was Palpatine in Revenge of the Sith? Back when Viggo Mortensen was capturing so many imaginations in 2002 and 2003, a REHupan proudly reprinted a letter he’d sent to his local newspaper that anointed Bush the American Aragorn, the hero-king who was defending the West against the Evil gathering in the East.

Was there ever a time when popular culture did not lend itself to this sort of game, one that the left-handed and the right-handed both line up to play? The concept of a Manchurian candidate long ago escaped the control of Richard Condon or John Frankenheimer. High Noon, Rio Bravo, and High Plains Drifter have been arguing among themselves for decades (in his Playboy interview John Wayne labeled High Noon “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my life”. Richard Slotkin’s Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth Century America is a book I dote on (and may well have quoted from more than from Howard’s own works during my REHupa years), and yet once in a great while a mulish part of me wonders, can every single Western between 1962 and 1976 really have been about Vietnam?

Mark didn’t backtrack to Batman Begins in his post; when I recently caught up with Christopher Nolan’s first venture into cowled cinema I was disappointed by Ras Al Ghul’s key speeches: “The League of Shadows has been a check against human corruption for thousands of years. We sacked Rome, loaded trade ships with plague rats, burned London to the ground. Every time a civilization reaches the pinnacle of its decadence, we return to restore the balance.” The Liam Neeson character also says “Gotham’s time has come, like Constantinople or Rome before it, the city has become a breeding ground for suffering and injustice. It is beyond saving and must be allowed to die.” First of all, did London truly become a markedly more virtuous place after the Great Fire of 1666? Also, Rome and Constantinople are rather obvious and/or timid choices; listing, say, Mycenae, Persepolis, and Teotihuacan as ancient targets of the League and Paris in 1789, St. Petersburg in 1917, Berlin in 1933 and Moscow in 1991 as more modern ones would have been much more thought-provoking. Still, for the REH-minded the League’s mission statement is interesting, as if some third force had barged into “A Song of the Naked Lands” to fulfill the function Howard gives to the barbarians. The League would seem to be half Old Testament deity frowning at the goings-on in the Cities of the Plain and half predator with its nostrils permanently flared to detect the rotten-ripe, incipient-carrion scent of intensely perishable civilizations.

It took the talents of Frank Miller, Alan Moore, and Grant Morrison to lure me into the DC Universe; when my childhood loyalties were being formed, Marvel’s chief competitor was about as hip and happening as The Lawrence Welk Show. So I’m no expert on Gotham City, but I’m struck by how isolated Nolan’s conurbation is, how detached from both the American polity — if memory serves the National Guard is mentioned once in 2 films, the FBI not at all — and DC-at-the-macro-level (I’ve read that in at least one storyline in the comic books, the Feds cordoned off the city to prevent its madness from infecting the rest of the country). Back when he was preparing to overhaul the series, the director mentioned wanting a Gotham in which viewers would be “completely immersed to the point that you do not feel its boundaries,” and that’s what he delivers, Chicago as hinterland-less Megalopolis, a City of Broad Shoulders faltering under the burdens it must bear all alone in a fallen world.

As The Atlantic‘s Matt Yglesias observed

One interesting thing about the film is what a difference it makes to rip Batman out of the context of the broader DC universe. The DCU’s other anchor character, Superman, is far more powerful than Batman. And of course Superman’s hardly alone in this regard — Green Lantern, Wonder Woman, etc. all wield vast power and even lesser lights like the Flash outpace Batman by far.

In that context, Batman rather uniquely doesn’t suffer from a substantial legitimacy problem. You don’t look at Batman and say “no man should wield this much power” in a world where Superman can see through walls. It’s those other guys who have legitimacy problems and Batman is one of the important checks on them — especially on Superman, who specifically entrusts a kryptonite ring to Batman for that purpose. This does pose a “who watches the watchmen” issue explored in Tower of Babel and elsewhere, but in a basic sense we’re supposed to be glad that Batman has so many gizmos not because we’re naive about power but because in the context of all these super-powered super-heroes it’s genuinely less threatening than such a person would be in the real world.

Yglesias’ Supes-invocation is very much in keeping with the “big blue schoolboy” who’s such an ominous (because his omnipotence is now at the beck and call of the gummint) figure in The Dark Knight Returns. The miracle of human diversity being what it is, blogger Lance Mannion differs, reading the new movie’s dismal today as the best possible justification for a Man of Tomorrow:

What The Dark Knight did, and did pretty well, I think, was clear a space in the Batman myth that can only be filled by one hero, who is not Batman. We may not get to see the series completed because his movie, the one that was intended to start the series that was going to intersect with the Batman movies, bombed. But the space for him is there and it doesn’t have to be filled on the screen because it’s easy to fill it in our imaginations. The ending of The Dark Knight contains the whole story of the Knight of Light. Look! Up in the sky…

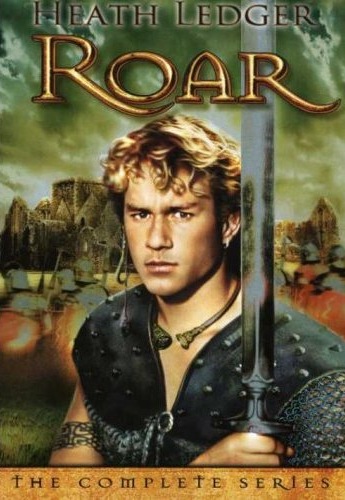

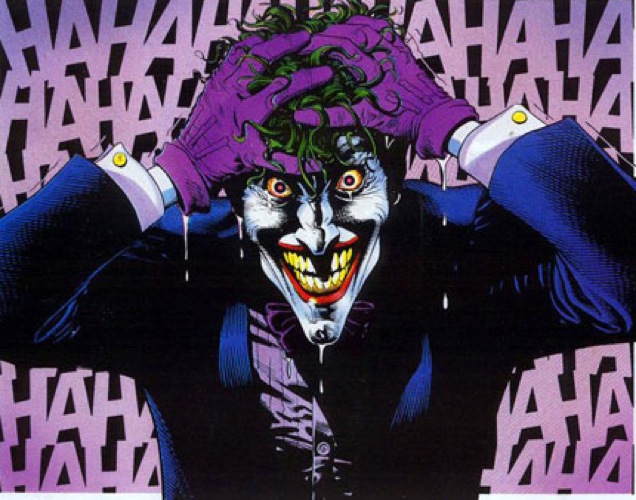

Turning to the Joker, Heath Ledger’s version is as advertised, a second career-defining triumph to go with his Ennis Del Mar in Brokeback (striking that the one character weaponizes words, where the other is wounded by his inability to summon them). It’s jolting to recall that 11 summers ago, Morgan Holmes and I were ridiculing Roar, a Fox import in which Ledger’s princeling led the resistance to a Roman invasion of the Emerald Isle (We know from Tacitus that his father-in-law Agricola believed Hibernia could be conquered with but one legion and a handful of auxiliaries, but in Roar the legionaries are led by. . .a Queen Diana?)

Most of us are familiar with the Joker’s antecedents, specifically the fact that Bill Finger and Bob Kane were inspired by this guy in The Man Who Laughs (1928):

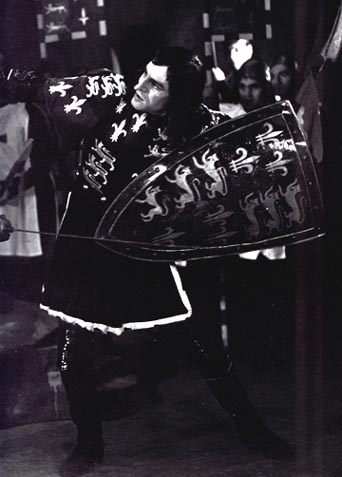

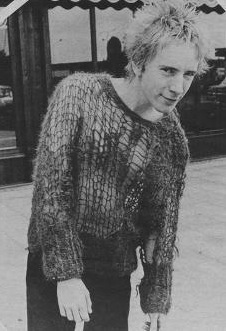

I’d like to trace an alternate ancestry for Ledger’s Joker, one that will make more sense to those who’ve seen The Filth and the Fury, Julien Temple’s follow-up/rebuttal to The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (1980). Where the first film is an agenda-serving mockumentary, the second is a rockumentary that returns to the Pistols all of their capacity for property-and-propriety damage. And throughout Filth a black-avised media-ghost manifests himself every few minutes: Laurence Olivier’s Richard III.

Despite the dreary truth that the outcome of Bosworth Field is never in doubt, in a mysterious way, Richard has always routed the Tudor propaganda that Shakespeare dramatized. Even before he gets his own play, the twisted younger son of the House of York is describing himself as “like to chaos, or an unlick’d bear whelp” in Henry VI, Part 3; for Stephen Greenblatt, he’s “a waking nightmare,” for Peggy Ender the very avatar of “the dregs of history in its demonic phase.” Olivier, of course, took this malediction clothed in flesh and ran, or at least limped energetically, with it.

Looking back on the “shoddy third-rate version of reality” to which Johnny Rotten was a reaction, John Lydon admits “In a weird way that whole persona of, say, Richard III helped when I joined the Sex Pistols: deformed, hilarious, grotesque. . .bizarre characters that somehow, through all of their deformities, achieved something.” He later observes, “There’s a sense of comedy in the English, even in your grimmest moments”: Richard’s cue to pop up again. “Let’s call it chaos!” his voice urges on the soundtrack. During his commentary track for The Filth and the Fury, Julien Temple remarks that Lydon “did identify in a strange way with Richard III and he had that illness that gave him a kind of hunchback and when you saw him at the microphone you know it certainly wasn’t Elvis Presley. It was, you know, the leer and the slouch and the grin and the stare were things that came from further back than that, you know, beyond Quasimodo, and I think he was always aware of Richard III, and there was a strange dialogue between his body language and that Olivier performance.”

Why have I dragged Rotten’s Richard-influence into this post? As per Sci Fi Wire, “Nolan–whose Dark Knight cast member Gary Oldman famously played Sex Pistols member Sid Vicious in a film biography–said he had in mind Vicious’ band mate Johnny Rotten when conceiving of the new Joker. ‘We very much took the view in looking at the character of the Joker that what’s strong about him is this idea of anarchy.'” Lindy Hemming, the film’s costume designer, also looked Rotten-ward, as she told WizardUniverse.com:

“You say, ‘What’s the rationale for him being able to dress like this?’ That’s when I started looking at the pop world and I ended up looking at the Sex Pistols and Johnny Rotten,” says Hemming. “I was just thinking, ‘Well, there are plenty of guys out there who actually are as extreme as this, and there’s nothing wrong with doing it.’ You’ve got to make it look like someone really dresses like this. It can’t just be, ‘Hello, I’m putting on my costume.’ It’s got to be wherever he lives and whatever he’s been doing, he’s been wearing that.”

The flattened-out Chicago accent Ledger uses for the Joker, so much creepier than a more theatrical or melodramatic choice would have been, obviously owes little to Rotten or Richard. And I don’t deny that there’s some of Malcolm McDowell’s Alex in the performance as well. Still, the murderous medieval schemer, the punk rock Antichrist, and the Harlequin of Hate are 3 mythic chaoticians, and the crucial lines with which the Crookback wins us over as henchmen at the outset of Richard III would do as well for Johnny Rotten or Ledger’s Joker:

I, that am curtail’d of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinish’d, sent before my time

Into this breathing world, scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them;

Why, I, in this weak piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity:

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover,

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Ledger’s Joker sticks around for hours after one exits the multiplex; forced to make conversation with him, I cast about me for REH texts where similar nihilism and chaos-cultivation can be found. My first stop was unsurprisingly the poems, where no leash laws are in effect, and our poet never had to answer to Isaac Howard, Hester Howard, or even his own super-ego. In his foreword to the Night Images collection, John Pocsik claimed “Nowhere else can the genius and vitality of Robert E. Howard be seen more clearly than in his poetry,” and that genius and vitality at times carry on as if staging a Black Mass in a commandeered Sunday school classroom. Steve Eng, responsible for what is the best starter’s kit the poems are ever likely to have, zeroes in on their frequent “cruel, bleak tone and godless amorality.” He pictures Howard “working on stories sleeplessly to the edge of exhaustion, then pushing away from the typewriter to pour some throbbing images and compressed narratives into the terse format of verse.”

Some of those images and narratives are rather like the jeers of a clown, and I don’t mean Pennywise. In “Red Thunder” Satan is encouraged to

Rush upon the cities, roaring in your might,

Break down the towers in the moon’s pale light,

Build a wall of corpses for God’s great sight,

Quench the red thunder in my brain this night.

The speaker of “The Dust Dance” revels in the fool’s motley Fate has dressed him in:

Ah, it’s little they knew when they molded me

For a pawn of their cosmic chess,

What a mummer wild, what an insane child

They fashioned from nothingness!

In “The Song of a Mad Minstrel” a “herald of horror and hate” arrives with “hideous spells, black chants and ghastly tunes.” “Sonnets Out of Bedlam” could almost be “Sonnets Out of Arkham (Asylum),” and Eng cites the “raging nihilism” of “A Hairy Chested Idealist Sings.” But perhaps the piece de resistance of Howard’s Joker-esque poetry is “Which Will Scarcely Be Understood”

The poets know that justice is a lie

That good and light are baubles filled with dust —

This world’s a slave-market where swine sell and buy,

This shambles where the howling cattle die,

Has blinded not their eyes with lies and lust.

These most special of poets are urged to “greet each slavering monster as a friend” and let “all the world resound with noisome mirth,” and the poem culminates in a future that could be that which the Nolan/Ledger villain aims to usher in for Gotham:

Break down the altars, let the streets run red,

Tramp down the race into the crawling slime;

Then where red Chaos lifts her serpent head,

The fiend be praised, we’ll pen the perfect rime.

Pen the perfect rime, devise the perfect joke — both reflect the anarchic impulse depoliticized and aestheticized, the engine that drives a Clown Prince of (C)Rime.

And if we search Howard’s fiction? Well, “Which Will Scarcely Be Understood” would surely be the favorite REH poem of a REH character who has scarcely been understood, or even noticed. It seems to me that Valerius comes close to being the Joker in The Hour of the Dragon‘s deck.

The only Aquilonian member of the novel’s Gang of Four is tall, fair-haired, and handsome; all of his deformities, as it turns out, are on the inside. Orastes tells us Valerius was “driven into exile by his royal kinsman, Namedides, and has been away from his native realm for years.” He’s been fairly far from well-adjustedness as well, and effectively introduces himself with his second speech in the novel: “What purgatory can be worse than life itself? So we are all damned together from birth. Besides, who would not sell his miserable soul for a throne?”

Apparently the last scion of the ancien regime, Valerius, although he takes advantage of Conan’s heirlessness, displays no interest in wedding and begetting his own heirs. He foresees a foreshortened future at best; “hatred and suspicion of his allies” gnaw at him. This is no ordinary Hyborian kinglet: “In his far journeyings he had encountered many strange races.” His skewed outlook is again evident when he admits that his Khitan-if-barely-human-hellhounds “have served me well enough, in your abominable way.”

Servius Galannus says to Conan, “Aquilonia has a king instead of the anarchy they feared,” but the joke, if not the Joker himself, is on Aquilonia. Albiona is more perceptive; she admits to herself that Valerius is comely, but “[knows] that when she [thinks] of the clasp of Valerius’ arms, her flesh [crawls] with an abhorrence greater than the fear of death.”

That her flesh is a good judge of character is confirmed by Chapter XXI, “Out of the Dust Shall Acheron Arise,” from first paragraph to last one of Howard’s most ambitious feats of storytelling.

Valerius, it seems, is ruling “like one touched with madness.” (Given what we know of Numedides/Namedides, the whole dynasty may have overindulged in cousin-marrying) His reign is “a series of feasts and wild debauches,” during which he is given to blaspheming while “sprawled drunken on the floor of the banquet hall wearing the golden crown and staining his royal purple robe” with wine. No post-coronation honeymoon has occurred, merely a rough anti-wooing, assault after assault upon the nation to which he has been joined: “Valerius plundered and raped and looted and destroyed until even Amalric protested.”

What’s going on? Something more interesting, and more interior, than a Caligula knockoff (although John Hurt at about the age he achieved immortality in I, Claudius would have been a perfect Valerius).

The new king is only too aware that he’s a cat’s-paw for Amalric, wielding borrowed power on sufferance:

Yet there was subtlety in his madness, so deep that not even Amalric guessed it. Perhaps the wild, chaotic years of wandering as an exile had bred in him a bitterness beyond common conception. Perhaps his loathing of his present position increased this bitterness to a kind of madness. At any event he lived with one desire: to cause the ruin of all who associated with him.

Accordingly, where Amalric dreams of a single empire, Valerius dreams of a single wasteland. He intends “to ruin the country so utterly that not even Amalric’s wealth could ever rebuild it. He [hates] the baron quite as much as he hated the Aquilonians, and [hopes] only to live to see the day when Aquilonia [lies] in utter ruin, and Tarascus and Amalric [are] locked in hopeless civil war” that will render Nemedia a calamitous chaos as well.

Now that’s an appetite for destruction. In his own way Valerius might be more disturbing than even Xaltotun, the mightiest son of a race of wizards. Like Salvatore Maroni, the Eric Roberts character in The Dark Knight, Amalric has let a mad dog off its leash.

As the signs and portents multiply, as Amalric & Co. thrust their heads into the lion’s jaws while trusting in the Dragon they’ve brought along, Valerius too-brightly suggests killing all of the restorationist forces with a single spell:

Xaltotun stared at the Aquilonian as if he read the full extent of the mocking madness that lurked in those wayward eyes.

Another brilliant touch in a novel chockablock with them; the Pythonian knows what he’s dealing with, can read Valerius like a nihilist manifesto. After Xaltotun details his plan to wash away Conan’s hopes, Howard tells us

Valerius laughed as he always laughed at the prospect of the ruin of either friend or foe, and drew a restless hand jerkily through his unruly yellow locks.

I wouldn’t be surprised if from now on when this particular conclave plays out in my head, the laughter, the jerky gesture, and the (unwashed) yellow locks are all Heath Ledger’s.

Howard has one last ace, or joker, up his sleeve; his unforgettable, laff-riot chaosmonger meets his match in another maddened soul of his own manufacturing: Tiberias, of whom we’re told “His eyes glared through the tangle of his matted hair as he half crouched before the baron.” This worthy’s “outstretched, upturned hands [are] spread like quivering claws” while his body writhes “in strange convulsions.” Another choice role for a Hurt, or a Ledger. Is there a more lurid-yet-lucid example of the “He who laughs last” principle in all of fiction than when, having spoken his vengeance-is-ours piece to Valerius, Tiberias slumps earthward, “still laughing ghastlily through a gurgle of gushing blood”? We know from Patrice Louinet that Howard did not insert the Tiberias sequence until the final stage of the novel’s composition, a case where late-arriving inspiration was a welcome guest indeed.

I don’t want to overdo likening Valerius to the Joker; as Mark pointed out, the people of Gotham acquit themselves better than the people of Tarantia, who in Zelata’s unforgiving verdict “have sold themselves to the slavers and the butchers.” More importantly, Ledger’s villain ridicules the very notion of an origin story or a motivating Ur-trauma; whereas much of Valerius is perhaps explicable by way of his Namedidean banishment and subsequent pilgrimages to the acid-disfigured, misanthropy-desecrated shrines of his own psyche. But when someone convinces us that he worships nothing-with-a-capital-N on the page or on the screen, it’s a darkling accomplishment, and with this character, Howard executed a thumbnail sketch with the nail’s-edge honed enough to sever a major artery.