Wheel of Pain, Tree of Woe, Throne of Tinfoil, Or, The Daze of Highly Insulting Adventure

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Here at TC Central a schism wider than the Hyrkanian steppes has long separated me from site-founder Leo Grin and Silver-Key–wielder Brian Murphy. Is John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian Li’ Abner versus the Moonies, as Karl Edward Wagner discerned so many years ago, or the most stirring sword-and-sorcery epic ever filmed? Well now [redacted], who posts as “Taranaich” at the Conan.com REH Forum, has graciously given us permission to run El Ingenioso Bàrbaro Rey Konahn de Simaria, an attempt at reconciling the Howard and Milius Conans that far surpasses the L. Sprague and Catherine Crook de Camp CtB novelization. Mr. [redacted] is clearly the greatest Scotsman since Sean Connery, and Gordon Brown should knight him forthwith:

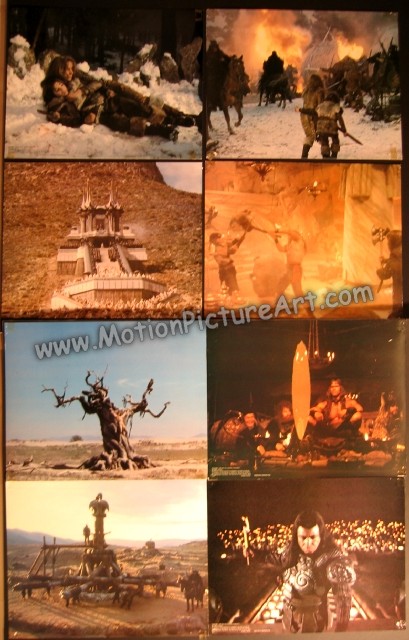

The film starts in the northern mountains of Brythunia. There, a tiny backwards village lies, far away from the rest of the world. The Simarians are a comfy folk living on the northern border, originally founded by a small community of luddites shunning the civilized wonders of Brythunia for a more “honest” rural life. Using distorted and piecemeal information gathered from drunk adventurers and senile folklorists, they model themselves after the Cimmerians, though their society leaves a lot to be desired in terms of accuracy. They worship Krumm, a mashup of Cimmerian and Nordic mythology whitewashed into a benevolent deity to suit their drippy ideals. Not actually knowing how to make proper swords, they use simple casting techniques to create attractive but impractical replicas: since they rarely meet other people, they never actually test their weapons in combat. This is the tribe of Konahn. Young Konahn has a happy childhood with his nice dad and hot mother, with no bandits or dangerous beasts to contend with, and no feudal lords to oppress them.

However, Konahn’s life is torn apart when the Riders of Thulsa Doom come. Thulsa Doom was originally Jamsh’el Jon, a Kushite scribe working for a minor Stygian priest, who started to get delusions of grandeur, and changed his name to that of the famed Thurian-era sorcerer. It wasn’t until he made a laughable attempt to usurp Thoth-Amon that he was banished, though the ineptitude of his actions were so amusing, Thoth-Amon let him live. He travels around the little kingdoms of the Corinthian Marches, where he joins up with Rexor and Thorgrim, and their band of “Vanir.” They are Gundermen, but a bit touched in the head, and pretend to be Vanir warriors — Rexor with a ludicrous triple axe, and Thorgrim with an infeasibly huge hammer. At some point, Doom discovers an ancient tome of great sorcerous power: he can barely understand most of it, but learns a few interesting parlour tricks like mesmerism, snake-charming and the illusion of turning into a snake. They try in vain to find communities to enslave using this power, but even the most tiny villages put up too much of a fight – until they learn of the Simarian village in the north.

Mother and father fight valiantly, but even their replica swords are not enough to fight against the LARPVanir’s slightly better made replicas. Father is killed by some mangy dogs, and Doom hypnotises Konahn’s mother before decapitating her in the first and last display of fighting prowess he ever achieves. Konahn and his fellow Simarian children are then taken to a mill way in the Corinthian Marches: ostensibly it’s a grain mill, but in fact it’s a great exercise in futility to break spirit and increase strength for heavy labour (Quite why the slavemaster didn’t take them to an actual grain mill to maximise profits is unknown, but likely due to his unholy crossbreeding between a Zamorian imbecile and a she-ape that escaped from a Hyrkanian circus). Fed on a high-protein diet, Konahn’s muscles and mass balloon, and he is bought for a local fight pit. Even though he has no combat training, the fighters he is pitted against are similarly unexperienced, and are even sorrier fighters than he is. Against such useless opponents, Konahn cannot help but rise through the ranks. He then is taken to “The Far East”… which turns out to be the Eastern side of the desolate northern Corinthian marches, trained by “War Masters,” a crowd of Khitanophile wargamers presenting themselves as experts. Eventually they release Konahn, not because he became too strong, but because they heard their father was coming and wouldn’t take kindly to their use of his lunas.

The Simarian spends about a day in the wilderness, though it seems more like a month to the the casual observer. Chased by wild dogs, he comes across the “Atlantean Tomb,” and finds the “Atlantean Sword”: not an actual tomb, it is the remnants of an old museum where history enthusiasts and their protesting families would go to see a display of an Acheronian King. Taking the tin sword, he meets a harlot whose trick is to pretend to be an evil witch, complete with fake fangs and shimmering firework effect, which is a popular fetish in the northern marches. He is told he will find Doom in Zamora — conveniently nearby. Soon he meets Subotai, a “Hyrkanian Archer” who is actually the result of a Turanian rake’s dalliance with a Zamorian dancing girl and thus has little actual Hyrkanian archery skill; and Valeria, a celebrity impersonator who turns up to parties as the famed Red Brotherhood she-pirate.

They soon come to the Chadizar, “city” of wickedness, a devious Zamorian noble’s attempt to divert trade from the much grander Shadizar via the confusion over the name. They learn about the Cult of Shet — not in any way affiliated with the Cult of Set –which was created by Thulsa Doom. After their slave trade failed when it emerged that for all their impressive musculature their slaves weren’t actually any use for extended labour, Doom and the LARPVanir abandon it. After a number of failed ventures, they construct a complicated and ingenious — for them — scam, promising spiritual enlightenment and happiness in exchange for worshippers’ lunas, goods and property. They are astonished to learn that it works, and soon they have hundreds of gullible idiots giving them all their possessions for empty words and fakery.

Soon, the Gang of Three infiltrate one of the cult’s strongholds, which is defended about as well as could be imagined for such a two-bit operation. Unfortunately, they come upon Doom’s pet snake, which he kept heavily sedated for his own safety. Somehow the half-comatose snake is a deadly threat to the three, and they are forced to kill it. They capture The Eye of the Serpent, a big piece of glass, and luckily enough the old nobleman they sell it to is as uneducated as they are in determining the value of jewelry, and he gives them an enormous sum in exchange. Eventually, they are caught by “King” Osric of Ophir, really a mad old coot whose Seneschal is a horse and whose High Constable is a sugar bowl, who managed to con himself into a modest mansion styled into a lavish castle. He tasks them with rescuing his “daughter,” really just a temple girl who caught his eye.

Konahn then meets Akiro, a Khitan scoundrel claiming to be a mighty wizard, who hides out at a demon-haunted set of mounds, since he is too stupid to know the danger of the place and far too confident in his powers. Soon he arrives at the Mountain of Power, a Zamorian tomb Doom happened upon, bringing his horde of empty-headed worshippers made even more empty-headed through drugs and suggestion. Konahn infiltrates the priesthood, only to be captured by Rexor and Thorgrim. After an embarrassing amount of torture and crying, Doom orders Konahn to be crucified on the Tree of Woe.

Dying from heat exhaustion, Konahn imagines he is being pecked at by a vulture, when in fact it is a crag martin, which he heroically decapitates with his teeth. Soon Subotai saves him, but it requires ludicrous magic and sacrifice to revive Konahn (which turns out to be smoke and mirrors by Akiro to make himself feel important.) The gang go to the Mountain of Power, and crash Doom’s orgiastic feast, just has he’s doing his “turn into a snake” routine. Thorgrim manages to collapse an ancient support column with a wayward tap, which he naturally attributes to his mighty hammer instead of the column’s state of repair. As they escape, Doom uses a hypnotised snake as an arrow to shoot Valeria. Continuing the mashup of Cimmerian/Nordic religion, Konahn burns Valeria on a pyre.

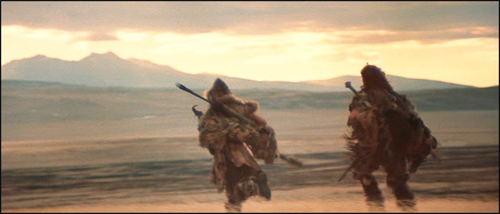

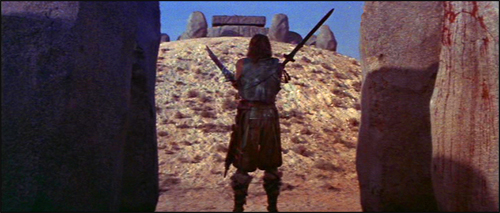

Doom and his cronies lead a small army of fellow Vanir enthusiasts — mostly men too stupid, sickly, ungainly or incompetent to serve in a real army — to steal back the girl. The four dispatch the army using a mix of rudimentary traps and the army’s own idiocy. Eventually, it is Rexor vs Konahn: Rexor is about to land the killing blow, when the reflection of Konahn’s replica Atlantean sword blinds him. Imagining Valeria returning to save him, Konahn is able to overcome the still half-blind Rexor, breaking his father’s poorly-made sword in the process, killing him. That night, Konahn comes to Doom. Doom attempts to hypnotise him, but Konahn is too stupid to be hypnotised, and cuts off Doom’s head with some difficulty. He hurls Doom’s head down the steps, and the Cult sheepishly starts to depart.

The epilogue shows a bearded Konahn seated on a throne, with Akiro’s dialogue. Then the camera zooms out a bit, and we find that Konahn is actually in a small cell in an asylum. King Conan and Publius peer through the small window. Publius remarks “It is indeed noble of you to grant asylum to such a poor deluded soul, sire! A lesser monarch would merely throw him into a dungeon to rule the rats and bones.” Conan replies “Well, can you blame him for abandoning his dull, bloodless reality and leaping into the delusion of kingship and glory? Let the man dream: what harm can he do? After all, no sane man could mistake the dotard in there for Conan the Cimmerian.”

But THAT… is another story!

DA DA DA DUN, DA-DA, DA, DA DA DA DUN, DA-DA, DA…

LEO RESPONDS: Conan the Destroyer and Red Sonja are well deserving of any mockery fans care to toss their way, but Conan the Barbarian is far too good for that. Nearly thirty years after it was released, it remains in the upper tier of fantasy films in general, and Sword-and-Sorcery in particular. Only Excalibur has ever matched it in portraying the sort of mythic, blood-and-guts battles and unabashedly masculine worldviews that S&S fans like myself treasure. Conan the Barbarian is pulp, for sure — but pulp was something REH understood and appreciated, especially the best of it, where important things were being said underneath the purple prose (or in a film’s case, purple effects). There are places where Milius’ film descends into the sort of schlocky realm of the worst of Howard’s Conan tales, but even then it maintains that raw earnestness that Howard had, and it ever strives for that Cthulhuian creepiness that manifested itself in Howard via sexy cults and gargantuan snakes and hypnotic sorcerers. For decades, fans have been making stupid arguments such as “the real Conan would have cut off his foot to escape his shackles before letting himself be a slave!”, but the truth is that there’s far more genuine Howard in the film than its more unimaginative critics give it credit for, powerful stuff that Howard would have thrilled to in the same way he admired, say, Harold Lamb. He may well have laughed at some of the liberties taken with his conception of Conan and the Hyborian Age, but in the end I’d bet the farm that Howard would have been as pleased as punch with the way it turned out, considering himself quite lucky given the cavalcade of turkeys that litter the field.

[redacted]’s MST3k-style piece is good for a few laughs, sure — but ultimately it’s no more accurate a portrayal of Milius’ Conan the Barbarian than Bored with the Rings was of Tolkien’s masterpiece. Me, I’ll stick with David C. Smith’s excellent analysis of the power and artistry thrumming under the low budget and sometimes amateurish but always heartfelt and genuine acting. It’s not Howard’s Conan, noted — but it’s deadly serious Sword-and-Sorcery, and far more a credit to the field than Peter Jackson’s risible estrogen-drenched interpretation of the Rings trilogy, which used an enormous budget, the most modern computer effects, excellent actors, and fantasy’s most beloved novel to manifest only the trappings of the genre, while the heart and soul of it — the respect for myth and saga as of old, the raw stuff that Tolkien and REH geeked on all their lives — was nowhere to be found. Tolkien would have been appalled (as his son Christopher was, to his eternal credit) at what Jackson, Walsh and Boyens did to the nobility of his characters and the ring and chime of his dialogue, supplanting both with pat Oprah aphorisms mouthed by Tiger Beat hobbits and Abercrombie & Fitch heroes, all of it accompanied by the insipid skirling and wailing of Howard Shore’s painfully out-of-place, pseudo-Irish flutes and fiddles. Conan the Barbarian has memorable, stirring dialogue from the guy who helped write Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, the Indianapolis speech from Jaws, and Apocalypse Now!, with many of those lines read by the likes of William Smith, James Earl Jones, and Max von Sydow. It has a magisterially barbaric, achingly lyrical gem of a score from one of the all-time great film composers, one that is as worthy of Howard’s Conan as Frazetta’s iconic paintings. Its cinematography appreciates the dust and heat and colors of the real natural world without the camera flying around as if on a Lord of the Rings: The Ride rollercoaster. It has deep wells of Nietzsche-inspired philosophy, sex with Sandahl Bergman, you-just-got-knocked-the-eff-out camels, and a blood-drenched bushido code. I’ll take all of that over stair-surfing elves, comic-relief dwarves, hobbit fart jokes, Isengard creature assembly lines, Enya love songs, and “Let’s hunt some orc!” one-liners any day.

STEVE SHUFFLES BACK OUT TO THE CENTER OF THE RING DESPITE HIS CORNERMAN’S PROTESTS: Like I said, a schism… I honestly envy you the fact that you caught Conan the Barbarian when you were at an age and of a receptivity that made the movie a profoundly transformational experience for you. Something like that happened with 2001 for me, but the genre was different and the astronauts’ helmets were sadly hornless. By 1982 I’d been reading Howard’s Conan stories for almost ten years, and skipping over the de Camp and Carter efforts for almost nine. CtB offers precious little sorcery for a nominal Sword-and-Sorcery film, and your invocation of Cthulhuvian creepiness makes me grimace in that Milius has about as much flair for the supernatural as the house director on Hee Haw. I won’t even get into the Riddle of Steel; I’m more concerned with the Riddle of Steal. If it wasn’t Howard’s Conan, why did it have to be Conan at all? Why not trot out a passive, pliable, pushed-around bumpkin all his own? If Milius had some thoughts he wanted to share on Jim Jones while absenting himself from a real world setting, why didn’t he create his own cult leader instead of helping himself to a Kull villain’s monicker? We know the answer — because Conan was a hot property by 1980, after the big sales for the Lancer/Ace series and the Marvel comics, and Milius wanted the name recognition without the characters and concepts behind the names. Poor Howard got his threat-geography wrong; his whole life he raged against the Eastern machine, fumed about exploitation and expropriation of Texas resources by carpetbaggers and opportunists from the older part of the country. He never saw California coming, never imagined that the vultures over Cross Plains would have Hollywood rondels on their wings.

And so we were treated to a Samson who’d seemingly let Delilah cut not his hair but his frontal lobe, Cimmerians who couldn’t outfight the Teletubbies, a dingy, down-market Lesser Nowheresvillia instead of shining kingdoms like blue mantles beneath the stars, a snake no self-respecting mongoose would bother with, and lumbering weapons-play seemingly choreographed and performed on a heavy-gravity planet. The audience I was part of that summer night back in ’82 guffawed at the hammer-of-the-clods overcompensation of Rexor and Thorgrim’s accessories every time they showed up onscreen — and yes, I know, we were flag-burning Manhattan anarcho-syndicalists, eager to let America’s Atlantean steel rust and marry camels instead of punching them. Many of us probably went on to cheer the Soviet paratroopers in Red Dawn. Doesn’t change the fact that CtB would have to ascend from its schlocky realm to reach the level of Howard’s worst Conan stories — better a slithering shadow than a dithering, docile, Wheel-yoked one. And I would bet not just the farm but a whole agribusiness that Howard would have been not amused but bemused at best and more likely profanity-spewing, to an extent usually reserved for Tourette’s sufferers. Hell, I wish biological, familially-minded Howard heirs still existed to sue Milius for slander after the smears he peddled about Howard on the DVD commentary track; it wasn’t enough for him to demonstrate his contempt for Howard’s work at feature-length, he had to caricature the dead creator as an ATF-raid-awaiting whackjob and shotgun self-splatterer.

Two scenes in just one of the Jackson films, Bernard Hill’s “Where are the horse and rider?” recitation and Miranda Otto’s singing of the (Anglo-Saxon) dirge at Théodred’s barrow capture more about heroic cultures than all the flexing and surfer-dude self-actualization in CtB. But let’s bring in someone we both respect, Tom Shippey, who wrote of the Legolas gags you mentioned “The addition of these commercially-driven scenelets need not be exaggerated: they pass quickly.” In connection with the “far green country” conversation between Gandalf and the (not very Tiger Beat-ish) Pippin after Minas Tirith’s walls have been breached he argues that ROTK-the-film is “talking to everyone, and talking to them about death, a subject well beyond the range of most Hollywood rhetoric. It is a good example of Jackson’s readiness to hold the screen and say something quietly.” And more generally he applauds the filmmaker’s success “in conveying much of the more obvious parts of Tolkien’s narrative core, many of them quite strikingly alien to Hollywood normality — the difference between Prime and Subsidiary Action, the differing styles of heroism, the need for pity as well as courage, the vulnerability of the good, the true cost of evil. It was brave of him to stay with the sad, muted, ambiguous ending of the original, with all that he leaves unsaid.”

I think Howard Shore’s LOTR-work is career-capping, even better than his long collaboration with David Cronenberg, a breathtaking use of Wagnerian techniques to achieve reassuringly non-Wagnerian ends. I’m sorry the “Irish” instrumentation doesn’t work for you; he was musically sketching the Shire as a mostly rural, bucolic society, and for long centuries in the Anglo-American imagination the “Celtic” has connoted the peripheral, the out-of-the-way, the non-up-to-the-minute. Shore leaned heavily on Scandinavian instruments for the scenes that introduce Rohan in The Two Towers, the sonic equivalent of the Northern European design motifs for Edoras and Meduseld; we’re being tipped to the fact that this is a Germanic asterisk-culture. As you know, I watch the Jackson films with my facial muscles rushing back and forth between Comedy Mask and Tragedy Mask on almost a line-by-line basis, but many, many pages of Tolkien’s dialogue are powerfully performed. How much Howard dialogue does CtB contain, apart from the simplified, decontextualized “Mirrors of Tuzun Thune”-loaner?

I would show the LOTR films to a severely dyslexic person curious about Tolkien’s appeal (if the audiobook option had been rejected). The Milius film to the same individual if he asked me about Howard? Never.

It occurs to me that we should take this debate on the road like Lincoln & Douglas, or Vladimir & Estragon, or Itchy & Scratchy.

BRIAN ADDS: Uh oh, what about someone who likes both Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and Milius’ Conan the Barbarian, as I do? I feel like I’m being pounded on the Anvil of Crom.