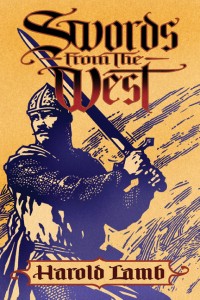

The Iron Men Ride: Swords From the West

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

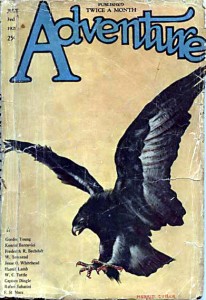

Adventure was considered the most prestigious pulp magazine in America. It was the very best that the pulps had to offer. And the very best author in Adventure was Harold Lamb.

Robert Weinberg, excerpted from his introduction to Swords From the West

I have been waiting for Swords From the West (or something very like it) for a long time. A massive book (over six hundred pages) bursting at the bindings with tales of conflict and courage, all sprung from the masterful pen of Harold Lamb.

The common thread which connects all the stories in this volume is that each one of the main protagonists are of European extraction. Sometimes their foes are fellow Europeans, other times the antagonists hail from points further East. As series editor, Howard Andrew Jones *, notes in his foreword:

What may be surprising is Lamb’s unprejudiced eye when portraying non-Western peoples. Lamb’s Mongolians and Arabs are painted with the same insight into motivation as his Western protagonists. He takes no shortcuts via stereotype: foreign does not necessarily equate with evil and villains can be found on either side of the cultural divide.

Geographically, Swords From the West embraces locales from France to the Roof of the World. Temporally, the tales stretch from about 1100AD to 1500AD. In other words, from the High Middle Ages through the early Renaissance. During his lifetime, Harold Lamb was considered an authority on that period. His reputation led Cecil B. DeMille to hire on Lamb as a screenwriter for the epic film, The Crusades. Lamb uber-scholar Jones quotes this anecdote from Higham’s 1973 bio of DeMille:

Harold Lamb was constantly present during the shooting of the siege [of Acre], dodging arrows and narrowly avoiding being crushed by the siege tower. “Is that realistic enough, Mr. Lamb?” the director asked him at the end of the first exhausting rehearsal of the conflict.

“Not nearly,” Lamb replied, wiping his spectacles. “Those soldiers seemed almost fond of each other. Medieval warriors were infinitely more sanguinary, let me assure you. What you need is a thousand battle axes red with blood.”

“A thousand battle axes red with blood.” That is how Harold Lamb saw the Middle Ages, not the anemic, bumbling, dandified version so many seem to cling to when they happen to ponder that era. Lamb’s vision is remarkably congruent with Robert E. Howard’s own. He once told Lovecraft that “the roaring, brawling, drunken, bawdy chaos of the Middle Ages” was his favorite milieu, outside of the American frontier. Very likely, part of REH’s outlook regarding the Middle Ages was shaped by many of the tales contained within Swords From the West. Howard avowed his deep admiration for Harold Lamb and Adventure magazine numerous times. To my mind, Lamb’s influence upon Robert E. Howard in regards to prose style, historical data and even general plot-lines is patent. I will note some of the more striking examples (such as they seem to me) as I review Swords From the West in the paragraphs below.

The first story in Swords From the West, “The Red Cock Crows,” was never published in Adventure, but instead appeared in the venerable Collier’s magazine circa 1928. Collier’s wanted “boy meets girl, gets girl” stories. Lamb, the consummate professional, obliged. That did not stop him from having his Scottish hero, Sir Bruce, dismember an assailant within the first two pages. A major character within this tale is a treacherous Byzantine. If Lamb ever wrote a yarn featuring an honorable East Roman, I don’t know of it; just as I am not aware of REH ever describing an honorable Kothian.

“The Golden Horde,” was published in Adventure. It introduced Nial O’Gordon, a landless swordsman born in Outremer. Nial is grim and a bit sullen, but likeable nonetheless (sort of like a certain Cimmerian). O’Gordon travels from the slave-port of Tana to Sarai, stronghold of Barka Khan, seeking adventure. He finds it, with double-crosses galore strewn across his path.

In “The Keeper of the Gate,” the reader catches up with O’Gordon in the Afghan highlands. Nial is on the run from friend and foe alike, headed for the wonders and mysteries of Kublai Khan’s Cathay. To get there, he must brave the gorge brooded over by the citadel of Gutchluk Khan, wizard-king of the Kara Kalpaks. A throne topples and the dead lie in heaps before Nial once again turns his face toward Kambalu. Unfortunately, Lamb wrote no more stories about the fell and mighty Scot.

Howard Andrew Jones believes that if Lamb had continued his tales of Nial O’Gordon (the stories were the last that he ever wrote for Adventure), such yarns would be the fictional creations most remembered today by Lamb’s devotees. O’Gordon is a charismatic and compelling character. If Lamb had written just half as many tales about the grim Scotsman as he did of Khlit the Cossack, I feel that O’Gordon would now be the marquee hero in his creator’s oeuvre.

The next jewel to be found in this treasure-trove of Lambiana is “The Grand Cham.” Published in the July 1, 1921 issue of Adventure, this tale is one that every Howardist should read, for the entertainment and for the historical value. In my opinion, this tale served as the template for Howard’s “The Lord of Samarcand.” The basic plot involves a man of Celtic extraction who harbors an undying grudge against Bayezid I. In order to bring about the Thunderbolt’s downfall, the protagonist lends his services to Tamerlane. Howard’s Donald mac Deesa or Lamb’s Michael Bearn? Lamb’s hero came first.

Bearn is one of the most interesting fictional characters in a collection overflowing with such. The man is indomitable. Whether he is shipwrecked, enslaved, crippled, abandoned on the Eurasian steppe or betrayed by his comrades, Bearn will not stop. He is a man with mighty resources of mind and body that never seem improbable nor unlikely. Howardian characters like Solomon Kane and John Norwald both may owe a debt of sorts to Bearn.

Pulp scholar Robert Weinberg considers “The Making of the Morning Star” to be Lamb’s best “crusader-meets-the-Mongols” story. He also asserts that if this tale had been “set on Barsoom or in Aquilonia, ‘The Making of the Morning Star’ would have been hailed as a fantasy masterpiece…” I find it hard to argue with that statement. From where I sit, this tale (published in 1924) inspired portions of “The Sowers of the Thunder” and “Red Blades of Black Cathay.” In my humble opinion, neither yarn quite matches up to “Morning Star.” I will even make the (admittedly unproveable) assertion that REH might have said the same.

Speaking of “Red Blades of Black Cathay,” another literary forebear to that yarn would seem to be “The Iron Man Rides.” Sir John Sheldon, Knight Hospitaller and emissary of Edward I, finds himself in Cathay before the throne of Kublai Khan. With him is Thamar, queen of the Georgians and daughter of Rusudan, after whom Lamb’s short novel, Rusudan, was named. An excellent short story.

Another classic tale is “Doom Rides In.” This one is a stray that Howard Jones tracked down from a 1932 issue of Cassell’s Magazine. It could easily be a story of any soldier of any era coming back to a home gone strange and wild, which is part of its appeal to me. Tales of fighting men, thought long-lost to war, who return to find all is not warm and well on the home-front, have been with us since Odysseus came back and cleaned house in Ithaka.

I have not covered each individual story from this collection for the sake of (relative) brevity. Rest assured that every single solitary tale within the covers of Swords From the West is worth reading.

Robert Weinberg has written a most excellent introduction for this volume called “The Long Journey of the Morning Star.” I led off with a quote from Bob and it seems fitting to end with one:

As a Lamb collector and fan for forty years, I envy all those who are reading his work for the first time. This book is a collection to be treasured, a book I guarantee you will read more than once.

*On the “Acknowledgments” page, Howard Jones dedicated Swords From the West to “the memory of heroic-fiction scholar, Steven Tompkins (1960-2009).” I think Tompk would have adored this collection.

**Art for “The Making of the Morning Star” by Michael Wm. Kaluta. Additional art by Tom Grindberg, as well as Bisley and Staples.