Something to Do with Deathlessness, Part Three: Splintered Shards of Time’s Reflection

Friday, September 12, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Part Two: Eyes We Dare Not Meet in Dreams

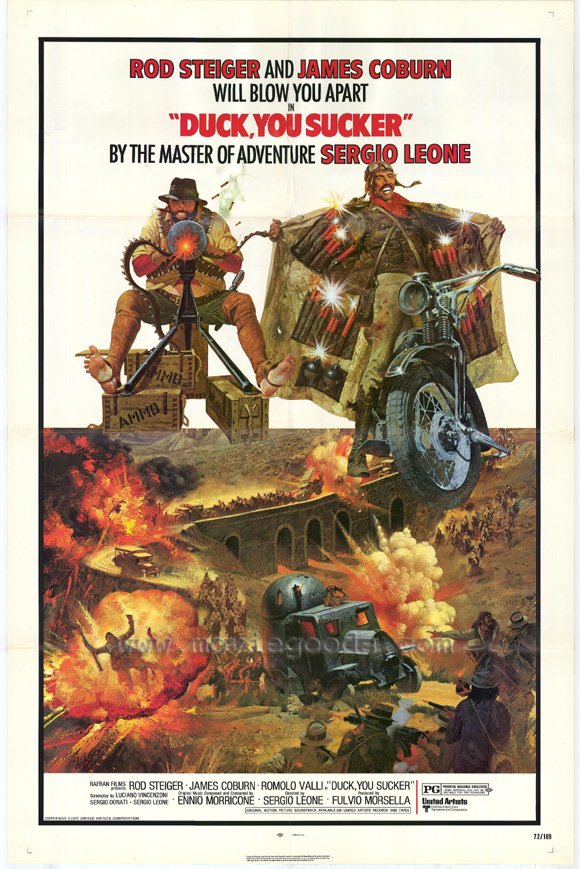

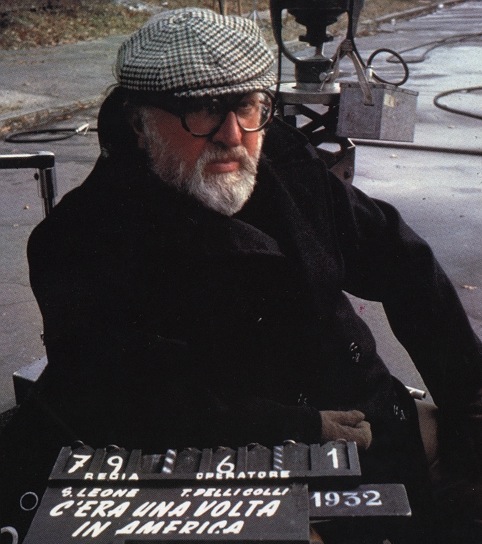

Sergio Leone’s 1972 film Duck, You Sucker was released as Once Upon a Time, the Revolution in France. Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, like Leone’s Sean Mallory, is a revolutionary, the very first revolutionary, and might nod understandingly at Mallory’s confession that “When I started using dynamite I believed in many things, all of it. . .Now I only believe in dynamite,” but Once Upon a Time, the Revolution works better as an alternate title for the 1979 Conan novel The Road of Kings than for any Kane story. Wagner wrote two Howard pastiches that redeemed the very concept of a Howard pastiche, and if The Road of Kings does not quite measure up to Legion from the Shadows it is in no small part because it is not the novel he had in mind. Just as Duck, You Sucker was a movie that Leone planned only to produce — in his head and heart he was already hard at work on Once Upon a Time in America — until the prospect of a walkout by Rod Steiger and James Coburn forced him back into the director’s chair, The Road of Kings is a fallback option, a salvage job necessitated by L. Sprague de Camp’s veto of Wagner’s original idea. The usurpation epic Day of the Lion was smothered in its cradle to make room for de Camp and Carter’s War-of-the-Roses-with-plastic-petals Conan the Liberator.

Duck, You Sucker was conceived as a riposte to spaghetti Westerns like Damiano Damiani’s A Bullet for the General or Sergio Corbucci’s A Professional Gun and Vamos a matar, compañeros, all of which involve uneasy alliances between cynical gringo or northern European mercenaries and initially apolitical campesinos who down tools and take up arms in response to injustice. Mallory, Leone’s northern European, is an explosives effort but also a full-time revolutionary, an IRA man with a British price on his head, while Juan Miranda is a bombastic bandit who is duped into a new role as “a great, grand and glorious hero of the revolution.” Wagner’s Northern mercenary is none other than Conan, ideologically naïve — his co-conspirators tease him about there being no word for “republic” in Cimmerian — but not a naïf. As a title, Day of the Lion was intended to evoke The Hour of the Dragon, and Wagner, than whom Howard has had no more alert and attentive reader, clearly picked up on the extent to which Zingara in the REH novel is not post-reconquista Spain but rather the anarchic Mexico of the same period covered by Duck, You Sucker.

The Road of Kings deals with political upheaval, but the upheaval is not a rebellion or revolt but an honest-to-Godless revolution of the sort we have come to know and dread since 1789. Conan, a sellsword sent to the gallows for his effrontery in winning a duel with a Zingaran officer, decides that no noose is good noose when he is the beneficiary of a last-minute rescue staged to save Santiddio, a sloganeering member of the White Rose. The leader of the raid, the streetwise Mordermi, later fills Conan in; the White Rose is “made up of the greatest intellects of Zingara, or so they tell me. They can quote to you from the massed political and social wisdom of countless philosophers and thinkers, living or long dead, in any language — but half of them couldn’t guess which end of a sword to grasp if you gave them three chances.”

Wagner has fun with the claptrap of high-minded sedition, pamphlets and committees and dogma-eat-dogma disputes: “Santiddio’s politics fell somewhere in between Avvinti’s doctrine of benevolent dictatorship through an intellectual elite and Carico’s classless utopia that would be achieved through an alliance of agrarian peasant and urban laborer.” He shares the suspicions that Leone expresses by way of Juan in Duck, You Sucker:

I know all about the revolutions and how they start. The people that read the books, they go to the people that don’t read the books — the poor people — and say, “Ho-ho, the time has come to have a change.” So the poor people make the change, eh? The people that read the books, they sit around the polished table, and they talk and talk, and eat and eat, and what happens to the poor people? They’re dead! And that’s your revolution.

Juan entertains hopes of a bright future in which he and Sean will dedicate themselves to the selective redistribution of wealth: “Juan & John, the especialistas in banks.” A similar comity develops between Mordermi and the northern barbarian in The Road of Kings:

Conan himself was no slouch when it came to the unlawful acquisition of property, and the Cimmerian gave away nothing in daring or ability to the more experienced Zingaran rogue. Admiration grew into a firm friendship between the two, tempered with an undercurrent of rivalry which, in their youth, neither man yet recognized as a threat.

Sean says that “If it’s a revolution, it’s confusion. . .When there’s confusion, a man who knows what he wants stands a chance of getting it,” and that is what occurs in The Road of Kings, but when Mordermi (the name, one of Wagner’s best, hints at something like “murder-skin” gets what he wants, his actions speak louder and more violently than Santiddio’s words:

This was not simply a change of rulers, Santiddio liked to point out, as when a palace revolt or coup d’etat does no more than exchange one set of scoundrels for another. Rather, the victory of the White Rose marked the beginning of a new social order for Zingara. The White Rose would draw up a new constitution for the people of Zingara — giving the people a voice in their governing, implementing new laws that would insure equal justice for all the people.

Soon Conan, who has been away from the capital city campaigning against enemies of the revolution, is dumbfounded to learn that those enemies now include erstwhile comrades: “Ranging along the row of severed heads, he was able to recognize others whose faces he thought he knew — men he remembered as friends and followers of Carico.” Mordermi tries to soothe the Cimmerian with snake-oil about emergency measures to maintain order, but his throne no longer rests upon the consent of the governed, but rather the Final Guard, petrified warriors created in the Pre-Cataclysmic Age as the last word in monarchical megalomania, the dead weight of the past made impervious un-flesh. Conan’s last words in the novel are a rejection of the crown that Mordermi no longer wears — “I will not change my mind. Not until I know whether it is the man who corrupts the power, or the power that corrupts the man” — but he might just as well have said to Santiddio, the other possible successor in the room, what Sean says to Juan: Duck, you sucker!

What else do Leone and Wagner share? Robert Cumbow has observed that “the centrality of family to Leone’s films is ever as victim rather than protagonist,” and that is true of Wagner’s work as well. Invited to make himself at home in A Fistful of Dollars, No Name replies “Well, I never found home all that great”; at the other end of Leone’s career, in Once Upon a Time in America, the young Noodles says “My old man’s praying and my old lady’s crying. Why should I go home?” We are presumably safe in seeing the reference to “the flaming death of Eden” in the “In the Wake of the Night” fragment as evidence of a similar attitude on the part of Kane.

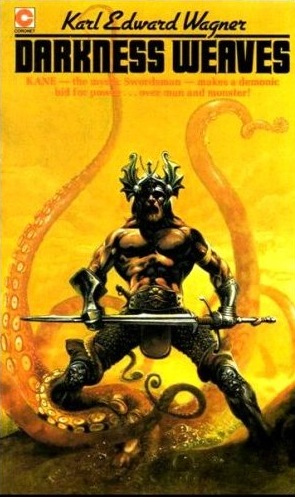

Bloodstone recapitulates Kane’s primal Edenic trauma of learning that he is just a pawn or plaything. Gerwein, the novel’s high priestess of Shenan, takes advantage of a crisis to order the mass sacrifice of “frail blooms we’ve nurtured since birth.” The Bloodstone-entity itself is maddened by the realization that its spacefaring brothers are as one “with the dust of an eons-forgotten war.” Neither set of royal brothers in the Netisten family has a happy time of it in Darkness Weaves, as is also the case with the Esanti siblings in The Road of Kings. The Vareishi children of “Misericorde” murder their father after he kills his brother, and Puriali is eager to move against half-siblings. And behind all of the rifts and ruptures is the ur-dysfunctional family, Kane, his brother Abel, his father Adam, his stepmother Eve, and his birth mother Lilith, who is never named but alluded to or obliquely invoked in “Raven’s Eyrie” and “Misericorde.” Their story might have been told, or retold and retrofitted to Wagner’s specifications, in Black Eden.

Where the altars of God and Family are profaned, that of intelligence is respected. Ramon Rojo is himself just intelligent enough to be perturbed by another’s brain after meeting No Name in A Fistful of Dollars: “I don’t like that Americano. He’s too smart to be just a hired fighter. . .He’s fast on the trigger but he’s also intelligent.” Wagner told Bradley H. Sinor, “What I wanted to do was to create a mysterious amoral character, far more intelligent and far more physically powerful than his adversaries,” and it is noteworthy that intelligence precedes physical power in his list of desiderata. Worth citing in this respect is the best of the early critical works on Eastwood’s filmography, David Downing and Gary Herman’s 1977 Clint Eastwood: All-American Anti-Hero:

His claim to heroism rests on no superior moral stand, no devotion to Love or the Law. Neither does it rest on an indifference to human life. Everyone is indifferent to that. It rests partly on his strength, determination and skill with a gun (the traditional values of the American western hero), but even more on his use of intelligence (the traditional European value) to manipulate his environment.

Dave Kehr likewise stresses in his 1985 article “A Fistful of Eastwood” that No Name’s “most active quality is his intelligence. Though skilled in violence, he is more skilled in strategy and human psychology.” When we learn that M’Cori in Darkness Weaves is defined by “a lack of guile that bordered on simple-mindedness,” we know she is doomed.

Intelligence in Leone’s films and Wagner’s stories often amuses itself by playing games and playing roles. No Name plays variously an emissary for his offended mule, a mercenary who stays bought once bought, a drunkard, and an apparition in A Fistful of Dollars. Colonel Mortimer gains admission to Indio’s gang as an expert safe-opener in For a Few Dollars More, while Indio himself preaches a parable from the pulpit of a thoroughly deconsecrated church and baptizes his gun in holy water. Tuco and Angel Eyes pass themselves off as Confederate and Union non-coms respectively. Max, Noodles, and their friends masquerade as doctors to steal the police chief’s newborn son in Once Upon a Time in America.

Wagner’s players include Evingolis the werewolf-minstrel and Efrel, who wears two costumes, one of beauty and one of disfigurement, before her true demi-demon self is revealed in death. “Sing a Last Song of Valdesee” is a series of unmaskings; Kane, whom Manly Wade Wellman called an “Apostle of Blood” way back in Midnight Sun #1, is addressed as “Reverence.” The hapless M’Cori pretends to be playing “a role from a romantic drama” when she is really trapped in a revenge tragedy. In Dark Crusade, Kane, in a lion mask, and Orted, in a truth-in-advertising “mask of featureless black,” fortify themselves with alcohol to sit through “The Invincible March of the Sword of Sataki.”

The pageant itself was a long, loud, tumultuous affair — basically a series of tableaus and processions interspersed with dramatic speeches and noisy sham battles. A narrator supplied continuity and interpreted the action, while the chorus shouted chants and battle songs, musicians battered their instruments, and the stage crew dashed about with sets and sound effects. The overall effect was somewhere in between a morality play, a travesty, and a free-for-all.

Kane himself is portrayed by “a beefy actor in oversized armor, who forever rushed about shouting commands and imprecations, crushing all who stood before him,” and Wagner may be targeting the signifying-nothing sound-and-fury of other writer’s sword-and-sorcery when he writes that “Most parts were indistinguishable, so that the slain rank and file rose again between scenes, to do battle and be slain again.” But the masterstroke here is that would-be nemesis Jarvo, who is being harbored by the Theater Guild, hides in plain sight by playing himself — “part buffoon, part dastard.”

On Kordava’s Dancing Floor in The Road of Kings, Rimanendo’s executioner oversees “the preparations of his assistants with the businesslike air of a director who surveys the stage and the players before lifting the curtain on his drama.” Leone’s epigraph for Duck, You Sucker is a slightly truncated quotation from Chairman Mao: “The revolution is not a social dinner, a literary event, a drawing or an embroidery; it cannot be done with elegance and courtesy. The revolution is an act of violence.” But the revolution in The Road of Kings is ushered in by the robbery of the realm’s lords and ladies at King Rimanendo’s birthday masque, which the disgruntled Conan attends in “the horned helmet, scale armor and fur cloak of a Vanir warrior — a race he neither resembled nor loved” (While there he meets “an absurd portrayal of a barbarian swordswoman)”.

Mordermi is placed in a context of costumes and faux royalty from his first appearance: “In trunk hose and filigreed doublet of dark velvet, Mordermi might well be a prince of the blood, instead of prince of rogues.” At the masque he chooses the “idealized guise of King Rimanendo himself — in ermine robes, gilt mail, tinsel crown, powdered hair” and a carefully calculated amount of belly padding. Soon after the palace has been stormed he makes “a truly majestic figure in his court attire and golden crown.” Clothes make the man, and when Mordermi reaps the whirlwind he reacts by unmaking the man those clothes have made:

The king of Zingara wore dirty laborer’s garments and a patched cloak. His hair had been powdered to a mouldy gray, and when he pulled the bloody bandage back down over his face would blend into the crowd well enough.

No Name, Harmonica, and Kane have more than intelligence and gamesmanship working for them. They move in mysterious ways to bend space to their will, to get to where they’re going while seemingly dispensing with the going. Robert C. Cumbow notes “As a shot begins, No Name usually already occupies the frame. Or he enters the shot from the background or foreground near the center; rarely does he come in from the sides. Whether by moving or standing still, the camera tends to discover or reveal his presence, rather than forcing him to walk into the frame.”

Kane contrives to be reading over Sitilvon’s shoulder as she records data from a toxicological experiment in “Misericorde,” and in Dark Crusade he answers the call that Orted has not in fact made:

Orted whirled at the low voice. The door of his private chambers stood open. Limned at the threshold by the flickering lightning — a silhouetted figure, massive, all but filling the doorway. A pair of eyes blazed a hellish blue beneath the storm-tossed mane of red hair.

Pleddis, the sole surviving bounty killer at the end of “Raven’s Eyrie,” is so distraught by that from which he has escaped that he fails to consider that to which he has escaped:

He paused for breath, and awareness of his surroundings came to him. The huge inn lay in total silence.

“Where — where is everyone?” Pleddis called out.

“I’m right here,” said Kane, rising out of the shadow.

Wagner was just as good at the Leone-esque fadeout, as in that of “Sing a Last Song of Valdese”: “His heels touched the horse’s flanks, and Kane vanished into the mist as well. ” If entrances and exits are as important as what happens in between, it is because of another similarity between this director and this writer. In 1984 Leone told Pete Hamill that he was “not a director of action. . .more a director of gestures and silences.” Wagner said in one interview that “Rather than simply tell a story, I’m trying to re-create a mood or an emotion. I’m more interested in atmosphere than action,” and in another “What I really liked out of the Gothic novel was the careful — indeed, obsessive — attention to mood and atmosphere. Action was frequently at a standstill, if not slower.” These protestations may not seem convincing coming from two men who staged violence so unstintingly and unforgettably, but the emphasis on gestures and silences, mood and atmosphere is evident in what Oreste De Fornari describes as Leone’s “subtly entranced rhythm” of “enervating dilations, traumatic ellipses.” Kane, of course, has been more enervated by dilations and more traumatized by ellipses than any other human being, experiences conveyed by several interior monologues and his conversations with Dessylyn in “Undertow” and Rehhaile in “Cold Light.”

Thinking of Once Upon A Time in America and its extraordinary gestation period, Christopher Frayling contends that “the main character in this story had become time itself.” Time is the other main character in the Kane stories, and more of an arch-nemesis than Efrel or Orted or even Sathonys could ever be. Kane can ultimately kill his creator, and he can kill time for years or decades, but he can’t kill Time. “Just you wait, asshole. I’ll do something with your time,” is the promise of the young Max to Noodles after a squabble over a timepiece in Once Upon a Time in America, and he keeps his promise. Noodles is punished by losing too many years, Kane by gaining too many. Both characters look for the same way out; Arbas lets slip in Darkness Weaves that Kane sometimes “starts smoking too much opium,” and the end of Once Upon a Time in America is both shattering and serene: a blissed-out Noodles who, in the words of Adrian Martin, is now “suspended in some place, some ‘atopia’ beyond time, beyond narrative.”

Sergio Leone regretted his inability to “make time stand still. There are moments that you want to relive over and over, very slowly, moments that you never want to end.” He came close in the audaciously protracted sizing up and staring down that precedes his gunfights, the work of an artist who wants to have his cake more than he wants to eat it.

Kane could be talking about Leone’s films in “The Dark Muse” when he wonders “how closely does time in a dream world follow the span of time as we know it? There time moves in obedience to the dream, not to natural law — an hour may pass like a second, or the reverse.” Similar images can be found in Adrian Martin’s monograph on Once Upon a Time in America and John Mayer’s “Karl Edward Wagner: The Man and His Writings” in Nightshade #1: Martin refers to how “the film dances elsewhere in time,” while Mayer imagines Kane “sidestepping through the centuries.” Obviously neither dancing nor sidestepping is linear forward motion.

Wagner’s Acid Gothic, what he defined as “the distortion of linear time and shifting presentation of reality to recreate the structure of nightmare,” resulted in the reshuffling of the episodic deck in “Undertow,” in which dreary chronology gives way to something more meaningful. Having walled up Ostervor in a secret passageway in “Misericode,” Kane fetches him with the words “Time, after all, is only relative.” In “Mirage” we find “moments of time, disremembered fragments of a dream strangely caught up again,” while “Reflection for the Winter of My Soul” offers “frozen fragments of time” and “splintered shards of time’s reflection.” Elsewhere in the series, Wagner, like Leone, endeavors to arrest or detain time:

It seemed to him that in Jhanikest’s tower there existed a form of timelessness within the ever shifting patterns of the remainder of the universe, a refuge from time itself.

Time hung in an eerie stillness against the onrush of space. Seconds dwindled into meaningless splinters of eternity. Time was unreal.

Either a century ago or just that morning he had fled across the northern wastes — and for how long? It was nothing, for it was past and beyond him. His life was only a minute focus of time, an instant of the present balanced between centuries of past and an unknown duration of future existence. He felt a moment of vertigo, as his mind hung poised over time’s chasm.

Seconds of time move dreamlike, for they are final seconds — and all that happens in that instant before the brain knows it is dead is like the passage of a lifetime.

And the differences between Leone and Wagner? Leone had no use for science-fiction hardware, and neither No Name nor Harmonica shares Kane’s intellectual omnivorousness or his penchant for quoting the classical dramatists of earlier ages. More importantly, Wagner lacked an Ennio Morricone, or was forced to be his own Morricone. Bernardo Bertolucci, who contributed to the story of Once Upon a Time in the West, once said that Morricone’s music is so present as to be “almost a visual element in the film.” Wagner’s words were unassisted by Morricone’s epiphanies and cacophonies, his death knells and whipcracks, or his choruses of fallen angels and risen devils.

We have to set “The Song of Valdese” and “Reflections for the Winter of My Soul” (in the story of the same name) to music ourselves. When we’re told in “Satan’s Gun” that “to some twisted mind the asylum had become a church, the maddening howls a choir, the raging storm an organ,” it is difficult not to think of Morricone. The moment in Dark Crusade where a “black stallion’s heavy tread sounded like muffled drumbeats on the torn and spattered sod” calls for Morricone, as does this flashback in “Raven’s Eyrie”:

“Hang him,” Ionor pleaded, her memory reliving a scene eight years back. A memory of familiar faces turning purple, of limbs thrashing, a death dance from an impromptu gallows, while murder-crazed animals roared in laughter below.

But Wagner did not do too badly all by his lonesome, especially when it came to the ominous and the mournful:

Death came again to Demornte. Nine gaunt horses beat their hooves with hollow echo through the silent streets of Demornte, past the overgrown fields, past the empty, staring houses, past the mocking smiles of skeletons. Death had returned to Demornte flying varied standards — idealism, sadism, duty, vengeance, adventure. New banners, but it was death that marched beneath them, and the omniscient eyes of the deserted houses, of the laughing skulls recognized death and welcomed it home.

Kane could see the dead stirring now. See the smashed and burned and torn and fever-pocked and famine-eroded bodies rise from the moraine of unnumbered bones. See their spectral hordes march across the war-blasted forest, rise from the talus of broken bones below, drift through the shattered towers and rubble-choked streets and dance a writhing spiral about the obelisk of Lynortis.

Neither man was thrilled about being lumped together with inferior talents: “When they tell me that I am the father of the Italian Western, I have to ask ‘How many sons of bitches do you think I’ve spawned?'” Karl Edward Wagner also saw imitation not as the sincerest form of flattery but rather a kind of battery:

Perhaps the most obvious failing is a paucity of ideas, an exhaustion of once-new concepts that has damned heroic fantasy with an invidious legacy of stereotypes and clichés, to a slavish cloning and re-cloning of a few hallowed archetypes. (“Hold the Bologna on Mine,” Fantasy Newsletter, December, 1982)

In his “Friends Die” piece in Exorcisms and Ecstasies, Ramsey Campbell wrote “It’s possible to look back over [Wagner’s] career and grow steadily angrier — at the way his talent was so seldom appreciated, too often mispublished and under-publicised.” Leone was less poorly served, although none of his films after For a Few Dollars More was released at his preferred length in the United States, a dire trend that culminated in The Ladd Company’s lopped-off, lobotomized version of Once Upon a Time in America in 1984.

Klinure, the eponymous character of Wagner’s “The Dark Muse,” dwells “in the shadow of unfinished dreams — the dreams from which we awaken and never return to. Their ghosts wait forever in limbo, incomplete visions that man will never realize.” Both Leone and Wagner died too young and left unfinished dreams and incomplete visions with Klinure. A more magical world would contain Leone’s contemplated miniseries adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, his 20th-century Don Quixote with the old tilter-at-windmills standing in for America and Sancho Panza signifying Europe, or above all his epic-redefining, Shostakovich-synchronized epic about the siege of Leningrad, on the subject of which he said, “What can possibly follow that dream of America lost?…Death. And this new film will certainly be about death.” Just as Leone was wont to perform the staggeringly ambitious opening of Leningrad, in Christopher Frayling’s words, “as a party piece” while he dickered with the Soviets, Wagner treated lucky friends and fans to verbal previews of Black Eden, his own private Origin of Species and Ascent of Man, and In the Wake of the Night, in which readers were to sail “the strange seas of man’s birth” with Kethrid and Kane and dare “the fallen cities of earth’s elder races.” In a way he even predicted what was to come, or rather not come, in his early story “The Last Wolf,” which compares the last writer left in the world to “a minstrel when all the castles have fallen” and summons characters who were never committed to paper from “the limbo of unrealized creation.”

Both men died too young, but both live on as influences. John Woo’s blood operas from A Better Tomorrow and The Killer through Broken Arrow and Face/Off are inconceivable without there having been a Leone, and he also haunts Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, Robert Rodriguez’s Once Upon a Time in Mexico, and Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill. Wagner’s name may only be recognized by tens of thousands rather than millions, but Matthew Stover’s fantasy novels Heroes Die and The Blade of Tyshalle — not for the faint of heart or the simple of mind — preserve Wagner’s impatience with Good versus Evil storylines and feature a legendary assassin named. . .Caine. And although David Gemmell’s preoccupation with expiation, with good works in the final phases of bad lives, is not particularly Wagnerian, his novels frequently examine what it means to be a killer of killers, to inhabit violence as one’s native element the way a shark does seawater. Waylander the Slayer and Skilgannon the Damned would have much to discuss with Kane.

Wagner’s profile has remained higher on distant shores than in the U. S., and in 2008, his trophy-shelf already crowded with Arthur C. Clarke, John W. Campbell and Philip K. Dick Awards for his science fiction, U. K. author Richard Morgan turned his attention to sword-and-sorcery with The Steel Remains, a “Weird Old Epic Noir” that courts controversy and consternation to an extent that would have had Kane’s creator beaming. Sure enough, on the novel’s acknowledgements page, we find this:

In case the influences worn so prominently on the sleeve of this novel should remain unclear, thanks are due to the following, for initial, momentous inspiration, way back when:

To Michael Moorcock for Hawkmoon, Elric, and Corum

To the memory of Karl Edward Wagner for Kane

To the memory of Poul Anderson for The Broken Sword and The Dancer from Atlantis

Both Leone and Wagner were perfectionists, and neither was prolific, except when it came to producing classics. Here we would do well to recall Wagner’s Opyros speaking about the perfect poem:

“It should be a total sensory and emotional projection of the artist’s mind into the mind of the listener. He should identify fully with the perspective, the reality of the poem — share the thoughts, sense the atmosphere, see the visions, unite with the mood.”

The Roman director and the Knoxville fantasist accomplished just such total sensory and emotional projections, and year after year reward those who return to share their thoughts, see their visions, and unite with their moods. Any list of the essential sword-and-sorcery novels that fails to include Darkness Weaves and Dark Crusade is a travesty, while The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West have made themselves at home in the adobe pantheon of the Western. Actual immortality might indeed come to seem a curse, as it does to Kane; artistic immortality is a very different proposition, a fitting reward for maestros like Leone and Wagner. People like that have something inside, something to do with deathlessness.