Skulls and Dust… (Egypt’s curse is a deathly thing.)

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

The Persian slaughtered the Apis Bull;

(Ammon-Ra is a darksome king.)

And the brain fermented beneath his skull.

(Egypt’s curse is a deathly thing.)

He rode on the desert raider’s track;

(Ammon-Ra is a darksome king.)

No man of his gleaming hosts came back,

And the dust winds drifted sombre and black.

(Egypt’s curse is a deathly thing.)

The eons passed on the desert land;

(Ammon-Ra is a darksome king.)

And a stranger trod the shifting sand.

(Egypt’s curse is a deathly thing.)

His idle hand disturbed the dead;

(Ammon-Ra is a darksome king.)

Til he found Cambysses’ skull of dread

Whence the frenzied brain so long had fled,

That once held terrible visions red.

(Egypt’s curse is a deathly thing.)

And an asp crawled from the dust inside

(Ammon-Ra is a darksome king.)

And the stranger fell and gibbered and died.

(Egypt’s curse is a deathly thing.)

“Skulls and Dust,” by Robert E. Howard

“No man of his gleaming hosts came back.” Indeed. What REH (and Herodotus) said. Verification of Herodotus’ tale concerning Cambyses’ lost army has been a long time coming (sort of like what Howard said about the Picts and the Basques). The archaeological findings of twin Italian brothers in the sands of the eastern Sahara might finally solve a millennia-old mystery. Naysayers have scoffed at the veracity of the Man From Halicarnassus, but they may have to rearrange their paradigms now.

Italian archaeologists Alfredo and Angelo Castiglioni believe they have found evidence of the “lost army” of Cambyses II (called “Cambysses” in the Howard poem), which force was sent to coerce the priests of Amun at the Oracle of Siwa in 525 BC. Located about sixty miles south-west of Siwa, the site is in a location where no others thought to look. Such “out of the box” thinking has produced startling archaeological discoveries in the past.

Herodotus claimed that Cambyses, the son of Cyrus the Great, sent an army to the Oracle of Siwa. The priests of Amun (“Ammon-Ra” in Howard’s poem) refused to legitimize the rule of the Persian shahanshah, so Cambyses dispatched troops to adjust their attitude. According to Herodotus’ account, the army was overwhelmed by a sandstorm of unprecedented ferocity before ever reaching the sanctuary of Amun.

Many have sought in vain for the “lost army of Cambyses,” including Count László Almásy. So many have searched fruitlessly that archaeologists and historians in recent years have tended to utterly dismiss Herodotus’ account as a “folktale.” If the Castiglionis are correct, everyone was looking in the wrong place. The brothers identified a caravan route to Siwa dating all the way back to Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty. This route would have brought Cambyses’ forces in from the south-east; the back door to Siwa. A fairly sound plan if Mother Nature (or Ammon-Ra?) had not dealt Cambyses’ commanders a bad hand.

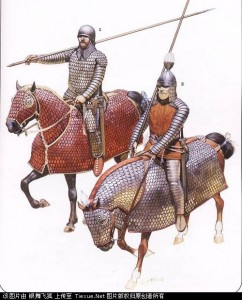

Those commanders would have had the typical polyglot imperial Persian army at their disposal: Babylonians, Bedouin, Levantines, Cypriots and Ionian Greeks. The armored fist of the force would have been the Persian heavy cavalry: the cataphracts and clibanari, ancestors of all heavy cavalry to follow, whether European knights or Fatimid memluks. The Castiglionis claim to have found a typically Persian horse-bit in their excavations.

Those commanders would have had the typical polyglot imperial Persian army at their disposal: Babylonians, Bedouin, Levantines, Cypriots and Ionian Greeks. The armored fist of the force would have been the Persian heavy cavalry: the cataphracts and clibanari, ancestors of all heavy cavalry to follow, whether European knights or Fatimid memluks. The Castiglionis claim to have found a typically Persian horse-bit in their excavations.

The idea of such a “lost army” has captivated story-tellers for centuries, whether one counts Herodotus amongst the spinners of yarns or not. Thomas Preston wrote a play about Cambyses around the time that Solomon Kane would have first taken ship. Shakespeare apparently made reference to Preston’s take on the Persian king in Henry IV (by way of Falstaff, one of REH’s favorite literary characters). Others have followed suit in the hundreds of years since. Poet, author and Friend of The Cimmerian, Richard L. Tierney, was unable to resist working Cambyses’ lost troops into his tale of Simon of Gitta, “The Worm of Urakhu.”

As shown in the verses that begin this post, Robert E. Howard could not withstand the lure of this tale himself. While he played a bit fast and loose with the facts as they were “known” even in his own day, Howard wrought a poem that thrums with the rhythms of the Sahara and hints at the abysses of Egyptian history.

At the center of “Skulls and Dust” stands “Cambysses,” mad as all those others whom the gods strike down. Perhaps it’s just me, but I sense almost as much of Saul of Gibeah (as REH saw him) about Cambyses as I do, say, Namedides. In “The Blood of Belshazzar,” Howard has Cambyses carry the eponymous, sorcerous jewel of the tale into Egypt with him, where it apparently drove him insane. Last, but not least, the army of Prince Almuric in “Xuthal of the Dusk” is likened to a “devastating sandstorm” before it finds itself annihilated (save for a single Cimmerian and his Brythunian sweetheart). The Kothian force is wiped out on the edge of the southern desert by Stygians, the (partial) ancestors of the priests of Siwa.