Rogues and the Dark Horse They Rode In On

Monday, June 23, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

One drawback to the hardcovers in which Dark Horse collects the story-sequences of its Conan comic is that they look fatally attractive on one’s bookshelf, and therefore disincentivize the regular purchase of the monthly comic books themselves. Having belatedly caught up with Rogues in the House and Other Stories, the hardbound showcase for the talents of Timothy Truman, Cary Nord, and Tomàs Giorello, I’m feeling so sheepish as to be at risk, or even more at risk, for anthrax, to say nothing of how unable I would be to meet the disappointed gazes of Jim and Ruth Keegan. Mea culpa, mea maxima led-astray-by-laziness culpa.

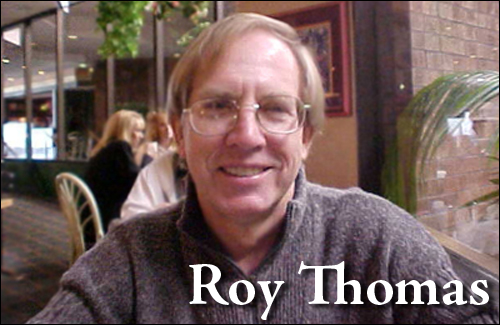

The lengthy histories of Conan the Barbarian, The Savage Sword of Conan and other Howard-derived forays into the comics medium and their role in seducing and sustaining several generations of sword-and-sorcery fans deserve much more study than was devoted to the topic in Paul Sammon’s Conan the Phenomenon (In Conan: The Ultimate Guide to the World’s Most Savage Hero, Roy Thomas elected to write from “within” the Thurian/Hyborian pseudohistorical continuum as a sort of post-Nemedian scholar, rather than as the key Marvel Comics figure that he was). I find sneers about “comic book dinks” as tiresome as “fanboy” self-hatred, and I’ve always thought that Roy Thomas was a better sword-and-sorcery writer than anyone in the Seventies except Karl Edward Wagner, Charles R. Saunders, and David C. Smith; witness “Devil-Wings Over Shadizar,” “The Hour of the Griffin,” “The Garden of Death and Life,” “The Last Ballad of Laza-Lanti,” and “The Citadel at the Center of Time.”

The Hyborian scholar part of me reacts to “Rogues in the House” as if to Sarin nerve gas. Most of us know that REH disclosed to Clark Ashton Smith: “I didn’t rewrite it even once. As I remember I only erased and changed one word in it, and then sent it out just as it was written. I had a splitting sick headache, too, when I wrote the first half, but that didn’t seem to affect my work any.” Me, I’ve often wondered if that splitting sick headache didn’t suppress Howard’s nominalist impulses; it’s hard to know where we are in “Rogues.” At a court festival [whose court?] Nabonidus the Red Priest, who was the real ruler of the city [of which city?]. . .Murilo contemplates voluntary exile — from where? The Maze is “frequented by the boldest rogues in the kingdom” — which kingdom? Murilo could almost be taunting us when he promises Conan a pouch of gold and a good horse: “With those, you can escape from the city and flee the country.” Gaaaahhhh.

What’s the big deal? Well, to name something is to make it more real, unless the naming is done by Michael Moorcock on a bad day. Howard or Tolkien, CAS or KEW, George R. R. Martin or Steven Erikson, I like to have my surroundings identified in a story of fantastic adventure, enjoy being able to weigh and bite down on the coinages of the author’s nomenclature, relish the chance to size up the background of a story’s foreground. Priorities differ; in his pendant article for the Rogues hardcover “Robert E. Howard: The Fourth Rogue,” [redacted] faults the Conan adventures that preceded “Rogues” but succeeded “Queen of the Black Coast” for too great an effort “to describe the geography and the age of [Howard’s] imagined world, sometimes to the detriment of the story.” For me, too much information is never enough when it comes to a Middle-earth, a Hyborian Age, or a Nehwon.

So “Rogues” meseemeth a little underfurnished or bare-bones, perhaps because inspiration jumped Howard all at once. The kingdom goes unnamed. The city goes unnamed. Cesspit Girl and her “punk” go unnamed, and the priest of Anu is just the priest of Anu. It’s often assumed that the story takes place in Corinthia, and names like Athicus and Petreus sound Corinthian, or what we imagine Corinthian names might sound like. Nabonidus’ name is the Hellenized version of the Neo-Babylonian monarch’s name (Nabû-na’id). In a way the person who could have settled the setting for us only added to the frustration: replying to P. Schuyler Miller, he wrote

I am not sure that the adventure chronicled in “Rogues in the House” occurred in Zamora. The presence of opposing factions of politics would seem to indicate otherwise, since Zamora was an absolute despotism where differing political opinions were not tolerated. I am of the opinion that the city was one of the small city-states lying just west of Zamora, and into which Conan had wandered after leaving Zamora.

Could be Corinthia; ‘just west of Zamora” is the right place for Corinthia, and those “small city-states” suggest the Greek polis, just as the reference to the Corinthian mercenaries in “Black Colossus” invokes the surplus fighting men who sprouted as if from dragon’s teeth in Greece and had to be exported, not only after the Peloponnesian War but before the Persian Wars (see Scott Oden‘s Homerically hard-edged novel about conquistadorial hoplites in a semi-senescent Egypt, Men of Bronze). But why couldn’t Howard have come right out and said Corinthia or Corinthian? Neither word appears in the story.

In “Xuthal of the Dusk” Conan is introduced in the second sentence of the first paragraph. In “The Pool of the Black One,” he emerges from the Western Ocean with an aplomb worthy of Joe Haldeman‘s Attar the Merman in the second paragraph. “Rogues” is different from its immediate predecessors, even a little diffident. Howard first introduces Nabonidus and Murilo, then the backstory involving the priest of Anu and the Gunderman deserter. When we do see Conan, it’s through Murilo’s eyes, and “the Cimmerian” isn’t even identified as being named Conan until Murilo is back home. Conan doesn’t take over as the POV character until the second chapter, after Murilo has decided to take matters into his own aristocratic hands and discovered the corpses of the dog and Joka chez Nabonidus. While the much younger thief-phase Conan of “Rogues” clearly hadn’t yet drifted out of Howard’s purview, perhaps the more mature, assured, and ambitious character of the preceding stories impeded authorial access to him at first. It’s almost as if Murilo and not Conan stood there and told Howard the story (Incidentally, the nobleman, like Amalric in the “Drums of Tombalku” fragment and of course Balthus in “Beyond the Black River,” is one of the rare occasions when we study Conan by way of a male rather than female POV character).

Still, nomenclature-challenged and Murilo-centric though it may be, “Rogues” rocks. Howard’s perfectly phrased and placed “One fled, one dead, one sleeping in a golden bed” epigraph always reminds me of Sergio Leone’s sardonic labeling of il buono, il brutto, and il cattivo at the beginning and especially the end of the first of his two masterpieces, and Nabonidus’s derisive “Rogues together! But not fools together” neatly encapsulates the Leone ethos. Perfumed hair and cesspool-diving, assignations and assassination, a holy man fixated on this world and a barbarian who speaks unselfconsciously of the next. “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and Dumas’ Cardinal Richelieu (“The head, clad in the familiar scarlet hood of the gown, was bent forward as if in meditation” cast long shadows, and the better angels of our nature are routed by the grinning apes of same — Howard came close to writing Le planète des singes decades before Pierre Boulle did.

Plus, way back in the dim dawn ages of genre expectations, this author is already turning them upside down. The archvillain’s henchman usurps his master’s part; it’s almost as if James Bond, assigned to eliminate Auric Goldfinger, were to sneak into the latter’s sanctum sanctorum only to find that Oddjob had rebelled and taken over. As for Nabonidus himself, it’s impossible to imagine him claiming, as does the Master of Yimsha, to have known “the kisses of the queens of hell.” He is less a caster of spells than someone upon whom technology has cast a spell; a set of Popular Mechanics back issues might excite him more than the iron-bound tome of Vathelos the Blind. At one point he swears by the soul of Mitra, and gains Murilo’s reluctant endorsement: “Even the Red Priest would not break that oath.” Having contained at one time both an Orastes (The Hour of the Dragon) and a Nabonidus, the Mitraic clergy is as fallible as any.

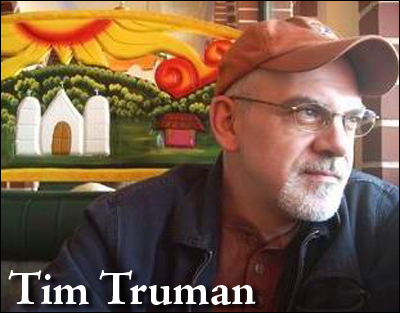

“I gradually discovered that adapting [“Rogues’] faithfully and having the gall to add two prelude chapters would be a more difficult task than I could ever have imagined. It was also one of the most exhilarating and rewarding creative endeavors I’ve ever undertaken,” Tim Truman confides. That shows in the result; his “Rogues” issues more than earn the dignity of hardcovers, reading as they do like a novella (still, the many-noveled career of David Gemmell notwithstanding, the optimum length for the best sword-and-sorcery). Nestor lingers as a character after his execution, and his corpse is spirited away to Yaralet (“The Hand of Nergal” and what will be the next storyline. Truman’s dialogue is as free with felicities as that of Roy Thomas at the top of his game; “You’ll never die, you bastard. You’re too ugly for your people’s heaven, and too pretty for their hell” might have made Howard himself smile, and “Conan could snatch the shine from a banker’s teeth” is a testimonial-and-a-half. We learn that raiding Picts did for the Gunderman’s parents, and Conan’s reflection that “it [is] a strange and satisfying thing, to kill an enemy twice” is as effective a punchline with the errant priest of Anu as is the taloned airlift Tsotha-lanti’s noggin endures in “The Scarlet Citadel.”

Lastly in terms of Truman’s little touches that say so much, I can only imagine [redacted]’s emotions when Conan climbs into the ring with the striped-jerseyed Stokosta the Seaman, who wants only to win enough gold to finance a return to his shipmates, and whose white bulldog growls at the Cimmerian once the sailor is out on his feet. Such is the authority of the Violet Crown Players that I heard Mark’s voice in my head playing Stokosta.

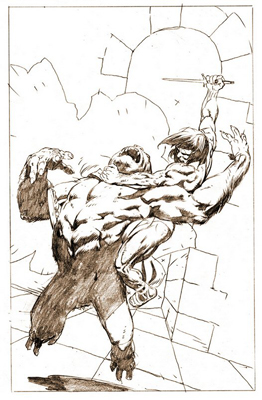

With due respect-bordering-on-veneration for the One True Frazetta, Argentine artist Tomàs Giorello captures Thak as successfully as anyone has since Nabonidus scooped up the orphaned cub in the mountains at the eastern edge of Zamora. Giorello’s closeups allow us to verify that a “monstrous body [houses] a brain and soul that [are] just budding awfully into something vaguely human.” One panel presents apeman-in-motion exactly as Howard describes, “his bowed legs hurtling his enormous body along at a terrifying gait”; the frisson here is akin to watching Tim Roth’s General Thade bust a genuinely simian move in the otherwise lamentable 2001 Tim Burton version of Planet of the Apes. Where Cary Nord’s art was italics, Giorello’s is more like boldface; heavier lines and more assertiveness are comforting to those of us who grew up with inkers embellishing (and sometimes all but ousting) pencillers.

But Howard fans always want more: more of the real thing, which now that The Last of the Trunk has been released is less and less likely, and more of the Howardian source material in any adaptation, no matter the format or venue. I’m sorry the adaptation’s Conan doesn’t get to say “Well, he’s traveled the road all rogues must walk at last,” and sorrier still that he loses his “I will count him among the chiefs whose souls I have sent into the dark, and my women will sing of him” lines after he admits that Thak was a man, not a beast. The missing words beautifully illustrate, as would woad daubings or an animal-teeth necklace, the extent to which his worldview is still tribal at this early stage.

Howard’s Nabonidus delights in letting Murilo know he’s onto him: “Before he died he told me many things, among others the name of the young nobleman who bribed him to filch state secrets, which the nobleman in turn sold to rival powers,” Later, he notes of Petreus’ band: “They had the same idea you had. Only their reasons were patriotic rather than selfish.” So it’s surprising that Truman, one of the GrimJack principals, felt an idealism-upgrade was necessary for Howard’s “white-handed thief”: “For too long, corruption and unrest had spoiled the kingdom. Prince Murilo dreamed of making the empire whole again.” (Also, which empire is that now?)

In the original story Nabonidus revels in the messy quietus of Petreus & Company: “They are all down, and the living tear the flesh of the dead with their slavering teeth.” Unlike Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith back in Conan the Barbarian #11, Dark Horse doesn’t have the old Comics Code breathing censoriously down their neck, so I wish this detail hadn’t been omitted, not because I’m a gorehound but because it’s the most graphic possible demonstration of how Thak reduces a group of men to the bestial state he himself is seeking to escape. Giorello wonderfully delivers on the twist that, in an abode full of death-traps, the villain’s undoing is a stool, but more could possibly have been done with Howard’s visual joke of the post-impact Red Priest who, although divested of his robes, lies “etched in crimson.”

My equally opinionated blog-brother Finn objects to “scrying mirrors that belong in some Clark Ashton Smith Atlantis story.” Actually the mirrors are used for spying, not scrying, and I’m not sure they’re out of place in the Hyborian Age. Think of the inhabitants of Xuthal, the lotophagous scions of “mental giants” who illumined their city with wall-jewels “fused with radium”; their food is not grown but concocted. Livia and her luckless brother in “The Vale of Lost Women” are members of the “house of Chelkus,” blueblooded scientists, and if we recall the “glassy knob which glowed with a golden radiance” in “Tombalku” and Xuchotlan gewgaws like Tolkemec’s crimson-knobbed, energy beam-firing jade wand in “Red Nails,” Nabonidus’ home security system can’t really be categorized as Smithian. The lost cities of Conan’s time (a few of which the Red Priest might have visited) would seem to be peopled by not only relict populations but early adopters.

Speaking of weird science, once the nationalists are as dead as they can be in Truman’s adaptation, Murilo turns on the Red Priest and possibly works a Richard Matheson allusion into his rebuke: “You’ve created unholy things for this hell-house, Nabonidus. Your soul will be damned for such magic!”

The other man isn’t having it: “Magic? Fool, this is no magic. I practice the arts of intellect, not superstition. The day will come when the power of magic will wither and be cast aside like the old gods, and only science will rule!” An succinct invocation of enlightenment as “endarkenment”; Nabonidus, a premature technocrat, would do very well indeed as a member of the Inner Party in a superstate like Oceania. Now it is Conan’s turn to speak up, and return us to the eternal severities of the Hyborian Age: “If that’s true, then answer this, priest — why are we in these pits, hiding from some animal? Someday, when all your science and civilization are likewise swept away, your kind will pray for a man with a sword.” So Nabonidus predicts the victory of sorcery’s callow rival science, whereupon Conan trumps him with the victory of steel, in a swordsman’s hands, over both. Note the echo of Conan’s farsightedness in ‘Beyond the Black River”: The time may come when they’ll see the barbarians swarming over the walls of the eastern cities.” I hope Mr. Truman will continue to summon Howard’s demons from out the vasty deep like this.

He’s not an outsider looking in at sword-and-sorcery; in his intro to Rogues in the House and Other Stories he recalls transferring Gardner Fox‘s Kothar, Barbarian Swordsman from a drugstore rack to his hot little hands back in 1967. Any mook can mention Thongor or Brak; Kothar is more insidery:

Kothar opened my eyes to a new genre — one that combined the elements of every sort of story that I was drawn to: the action of comics, the sense of otherwordliness and wonder of science fiction, the darkness and menace of horror, the drama of historical stories, and the timeless heroism of mythology.

I was disappointed when Kurt Busiek left the Dark Horse comic, and be damned to the squalling about the “bitch-slap” episode (a child cuffed during a couple of panels in a single issue, endlessly denounced by one fan in particular, strident as a human car alarm, whose gag reflex oddly never seems to have kicked in no matter how much the de Camp and Carter pastiches required him to swallow). I thought Busiek did mostly good work, with a standout sequence filling us in, much more memorably than did the Conan the Swordsman offering “Legions of the Dead,” on the reason for the Cimmerian’s lifelong detestation of the Hyperboreans. Rather than borrowing from the Kalevala (Pohiola, Vammatar) as did de Camp and Carter, Busiek played with the old, old Greek conceit of Hyperborea as a paradise secreted behind the North Wind, a preserve strolled by savants of lordly longevity but built on the corpses of captives drained of their life-force. But reading Rogues in the House and Other Stories turned out to be an act of contrition for my lack of faith in the Truman Administration: this West Virginian may not have been genetically engineered to be a Conan comics writer, but he’s certainly been generically engineered, through his work on GrimJack, Scout, Wilderness, and Straight Up to See the Sky. In his foreword to The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian, another artist, Mark Schultz, described the Conan of “Black Colossus” as “the veteran mercenary who begins to understand that he has it within him to go all the way, ” (those who are too quick to lump the story in as part of the Conan-and-the-ankle-clinger-of-the-month grouping should regard Schultz’s as a cautionary insight) so it’s serendipitous that a writer with a merc-antihero than whom there is none grittier in his background will be scripting Dark Horse’s back-to-#0 Conan the Cimmerian, which will deal with the barbarian-as-sellsword.

The editors and creators have moseyed on down the timeline a bit with miniseries like the chintzy chinoiserie of Conan and the Demons of Khitai and P. Craig Russell‘s rather too Melnibonean adaptation Conan and the Jewels of Gwahlur. Given Scout, set in a postapocalyptic Southwest where the Apache skillset of Truman’s Emanuel Santana is the only birthright that isn’t a death sentence, and Wilderness, a graphic novel about turncoat/turnskin and dark-side-of-Dan’l-Boone Simon Girty (among the dastards called for jury duty in The Devil and Daniel Webster), here’s hoping they turn Mr. Truman loose in the Pictish Wilderness, where “Wolves Beyond the Border” characters like the Girtyish Lord Valerian and Kwarada would be perfect for him. And his website treats us to a preview of an Edda-steeped project called Odin: The Wanderer; in the excerpt the one-eyed king of the Æsir opts to bring Loki back to Asgard, the decision that will breed so many stories and so much sorrow. The characters are conceived as armed-to-the-teeth ursinoids, so I wonder if Mr. Truman is already sick of questions about Iorek Byrnison and the other panserbjœrne (armored bears) in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. In any event, a yen for “the Northern thing” bodes well for any Conan the Cimmerian stories that cast a cold eye in a Nordheimrly direction.

So thanks to Messrs. Truman and Giorello, I’ve seen the error of my hardcover-awaiting ways and will revert to being a monthly buyer.