“Red Shadows”: Subgenre-Dawn’s Early Light?

Thursday, September 25, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

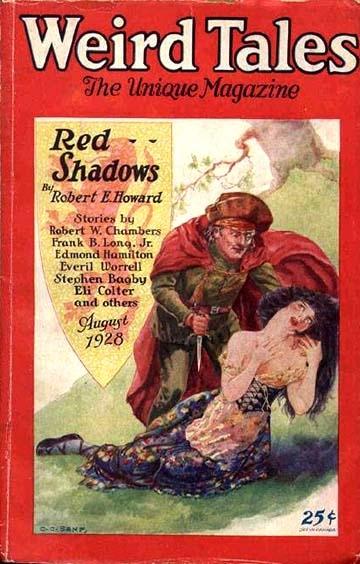

Next month if nothing happens the Weird Tales publishes my “Red Shadows” which according to the announcement is “Red Shadows on black trails — thrilling adventures and blood-freezing perils — savage magic and strange sacrifices to the Black God. The story moves swiftly and without the slightest letdown in interest through a series of startling episodes and wild adventure to end in a smashing climax in a glade of an African forest. A story that grips the reader and carries him along in utter fascination by its eery succession of strange and weird happenings.” The announcement does it a fair amount of justice I suppose.

Robert E. Howard to Tevis Clyde Smith, circa June 1928

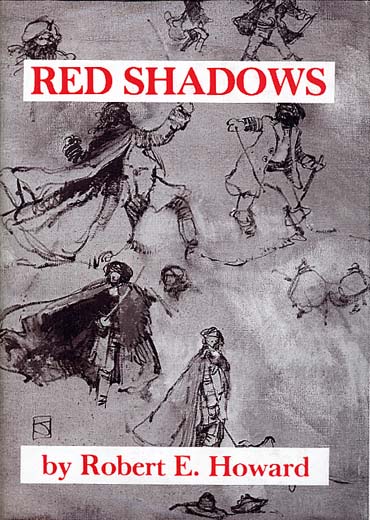

In “Conan the Argonaut,” their must-read lead article for the worth-the-wait TCV5n4, Morgan Holmes and George Knight say of ‘The Shadow Kingdom,” “That story was Sword-and-Sorcery’s magnificent coming-out party.” Howard’s antediluvian showstopper is usually seen that way, as the beginning of what has been such a beautiful friendship between fantasy, adventure, and horror in the form of a new subgenre. But every once in a while someone is moved to contest the consensus by asking, what about Solomon Kane? He beat Kull into print by a year; “Red Shadows” in the August 1928 Weird Tales was followed by “Skulls in the Stars” in the January 1929 issue. Why isn’t the Devonian (Devonshireman?) rather than the Atlantean accorded the status of having been first to climb into the cockpit as sword-and-sorcery’s test pilot?

My blog-brother Finn would seem to be one such dissenter; in “Two-Gun Musketeer: Robert E. Howard’s Weird Tales,” his introduction to Shadow Kingdoms: The Weird Works of Robert E. Howard, Volume One, Mark writes “Howard invented the sword and sorcery tale as we define it with his genre-breaking Solomon Kane.” He regards “The Shadow Kingdom” as then taking “the sword and sorcery concept one step further” by deleting “any semblance of the world we know.”

For me, this is one case where the conventional wisdom is actually wise rather than just conventional. “Red Shadows” is fer damn sure one of Howard’s early triumphs, the start of Solomon Kane’s true homecoming, as Patrick Burger and Paul Shovlin have pointed out in their work on the story, a return to a benighted Eden no longer guarded by angels but swarming with devils and the character’s discovery of a heart of darkness with which his own beats as one. But with this 1927 pulp event we are only in sword-and-sorcery’s antechamber or foyer. With the story Weird Tales would publish one year later, the story Howard had been living with and growing into for years (see Patrice Louinet’s “Atlantean Genesis”) he would step surefootedly across the subgenre’s threshold and onto Valusian soil, where the Snake-that-Speaks would be waiting.

So how is it that I classify “Red Shadows” as almost-but-not-quite sword-and-sorcery? The shortfall, the something-lacking, has nothing to do with setting; heroic fantasy need not occur in a Pre-Cataclysmic Age or the far future of Gardner Fox’s Yarth or Nyumbani or the Drenai-world. Our own terra infirma will do just fine, whether in the Averoigne-esque region around Joiry, the Sumeria of “The House of Arabu,” or the Hellenistic Tyre and Persia of “Adept’s Gambit.” Nor is an ancient or medieval backdrop a prerequisite; sword-and-sorcery can absorb more than a whiff of grapeshot, as the warship-dismasting cannonades and battlefield-raking barrages of Paul Kearney (The Monarchies of God, The Sea Beggars) demonstrate. David Gemmell’s Stormrider revels in its sworded and sorcerous doings against the Cavaliers-vs-Roundheads backdrop of the “Varlish” Civil War. Even the Enlightenment can be shrugged off; Christophe Gans’ Le Pacte de loups/Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001), to my way of thinking a far better S & S film than any of those that have trifled with REH characters, takes place in prerevolutionary, can’t-throw-a-baguette-without–hitting-a-materialist-philosophe France. But the eighteenth century is pushing it, and I can’t really imagine a nineteenth century sword-and-sorcery story; even Karl Edward Wagner’s “Hell Creek” reads more like a weird Western or Bierce-descended Civil War horror tale.

Although we shouldn’t look to Lin Carter as a final arbiter of anything save silliness, to help make my case “against” “Red Shadows” I’m going to cite his definition of sword-and-sorcery in the introduction to Conan the Buccaneer: “a fast-moving and colorful adventure story laid in a preindustrial world where magic works and the gods are real — a tale which pits an heroic warrior in direct conflict against the forces of supernatural evil.” Ignoring the distraction of whether “the gods are real,” I would argue that the direct conflict against the uncanny is important. Infinitely more thoughtful than Carter, in their Encyclopedia of Fantasy entry for S & S John Clute, Roz Kaveney, and David Langford similarly emphasize “muscular heroes in violent conflict with a variety of villains, chiefly wizards, witches, evil spirits and other creatures whose powers are — unlike the hero’s — supernatural in origin.” Violent conflict, direct conflict — for me the reason “Red Shadows” is a superb adventure story with extra helpings of supernaturally tinged atmosphere, but an also-ran as Howard’s first sword-and-sorcery story, is because sword flickers with moon-silvered brilliance in the foreground while sorcery merely broods in the background. Oh, we side-slip into our old friend Howardian fairyland with the very first sentence — “The moonlight shimmered hazily, making silvery mists of illusion among the shadowy trees” — but the ensuing “Men shall die for this” scene is the story’s mission statement and establishes its overriding priority: a man punishing other men, their leader in particular, for what they did to a young girl. Let’s parse some of Howard’s own remarks about “Red Shadows”:

. . .I wrote this story for the Weird Tales originally and then decided to try my luck with Argosy All-Story just as it was. So if a despised weird tale, whose whole minor tone is occultism, can create that much interest with a magazine which never publishes straight weird stuff, I don’t feel so much discouraged.

A “minor tone” of occultism, of N’Longa’s juju and the Black Gods, seems about right, with a corresponding major tone of the revenger’s trail and what Le Loup, mocking as always, calls “this fool’s dance about the world.” Note that in Howard’s February 1929 list of his fiction up until that point (ostensibly prepared for the edification of Tevis Clyde Smith), the capsule description of “Red Shadows” is “vengeance, a paranoid, voo-doo.” The supernatural comes in a distant third.

So while “Red Shadows” contains both swords and sorcery, the principal sword is never pitted against the sorcery. Kane’s prey throughout is Le Loup, a heretofore supreme predator, but a human one. Given the Puritan’s Mephistophelean nimbus, he himself would be the closest thing to a supernatural agent in the story were it not for what N’Longa does to King Songa. “Skulls in the Stars” meseemeth a ghost story, albeit an atypically bruising one (manhandled by SK, the Gideon ha’nt must wonder what the point of being ectoplasmic is). “Moon of Skulls” first displays modern heroic fantasy’s Haggard countenance, the lost city, race, or world, with a concomitant oubliette of Deep Time, and then Solomon Kane attains apotheosis as a sword-and-sorcery hero in “The Hills of the Dead” and “Wings in the Night,” while “The Footfalls Within,” which Howard himself poor-mouthed, offers a just-about-perfect balance between human foes (the Arab slavers) and inhuman ones (the demon imprisoned by the “first” Solomon). Such a balance is essential in what might be the most villain-intensive of all subgenres.

Jessica Amanda Salmonson writes in her “Thoughts on the Enjoyment of Heroic Fantasy” that “Heroic fantasy at its best observes things to be as menacing, amoral, simple and inevitable as dying. It can be read escapistly, but it is not inherently escapist. In our daily life we aren’t apt to get in a duel of steel, but anyone who passes through this life without dangerous encounters of any kind has got to be a milquetoast holed up in a dreary cell.” A worthwhile observation, and she could almost be alluding to Le Loup and “Monsieur Galahad” with that “duel of steel,” but her topic could just as easily be several varieties of adventure fiction or revenge narratives. Salmonson does not address the fantasy half of the term heroic fantasy, and neither does “Red Shadows,” at least not sufficiently to clinch the honorific of first sword-and-sorcery story. The Black Gods certainly function as a not-at-all Greek chorus, but nothing really lurches or lunges out of the past’s murk to imperil Kane (or the Africans he will take it upon himself to ward in later stories); he is the beneficiary rather than the target of N’Longa’s mojo-working.

Even if “Red Shadows” failed to get there firstest with the mostest, the story is a motherlode of textual richness. All of us who’ve pored over Howard’s career know his account, in a February 1928 letter to Tevis Clyde Smith of Lovecraftian length if not mood, of how “Solomon Kane” (the original title) was rejected by Argosy All-Story associate editor S. A. McWilliams. The blow was considerably cushioned by “a long personal letter:

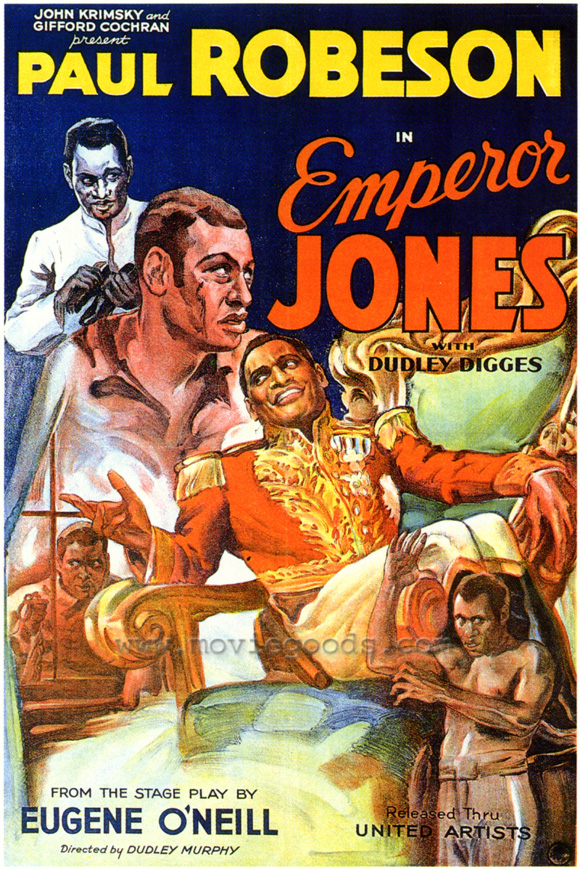

He says that I have “the stuff” if I “get steered right” so therefore he is giving me the reasons it was turned down in detail. He did, very concisely and clearly. He says that as the setting was the Middle Ages, I had too much “Eugene O’Neill jungle stuff” in the story (He’s not accusing me of plagiarizing).

Nowadays, despite Howard’s seeming unfamiliarity with Heart of Darkness, we’re probably more inclined to associate “Red Shadows,” Kane, and Le Loup with the Conrad short novel, Marlow and Kurtz, than with Eugene O’Neill:

You too are of the night (sang the drums); there is the strength of darkness, the strength of the primitive in you; come back down the ages; let us teach you, let us teach you (chanted the drums).

And here’s Conrad:

The thing was to know what he belonged to, how many powers of darkness claimed him for their own. He had taken a high seat among the devils of the land — I mean literally. . .How can you imagine what particular regions of the first ages a man’s untrammeled feet may take him into by way of solitude?

The African village to which Kane tracks Le Loup is even “on the river bank, but set back from the bay shore, the jungle hiding it from sight of the ship,” and my guess is that the Howard of a few years later, more attuned to the potentialities of the novelette and the novella, would have treated us to a journey upriver on a Zarkheba-style waterway in search of Le Loup. But McWilliams was onto something in the aforementioned long, personal letter, and I don’t remember any Howardist ever taking the time to pinpoint exactly what. He was likely thinking of O’Neill’s first success, The Emperor Jones (1920). A slightly shaky tryst between realism and expressionism, the play is racist enough to make “Red Shadows” come across like something co-authored by Ralph Ellison and Thurgood Marshall; one character, Lem, is described as “a heavy-set, ape-faced old savage of the extreme African type.” Still, with The Emperor Jones O’Neill made American theatrical history by creating the first dramatic lead for an African-American actor, and his text is worthy of notice in Howard Studies because, direct influence on the creator of Kane and Le Loup or not, it was part of the cultural Umwelt in which “Red Shadows” emerged from that white-hot Underwood. O’Neill’s most crucial stage direction decrees that the “insistent, triumphant pulsation” of talking drums must contextualize and comment on everything his protagonist Brutus Jones, a murderer and chain-gang escapee who’s ascended “from stowaway to Emperor” (on guess-which Caribbean island) says and does. Atavism and racial memory rear their age-old, age-ugly heads, and after being overthrown Jones fends off O’Neill’s “Little Formless Fears” — “black, shapeless,” and glitter-eyed — before entering the “brooding, implacable silence” of a Great Forest where a “Congo witch-doctor” bids him sacrifice himself to a Crocodile God who actually surfaces on stage!

The REH Bookshelf confirms that Howard knew at least some of O’Neill’s work, and even saw a one-act play performed. While he nowhere mentions The Emperor Jones, neither does he give vent to a “What the hell does Eugene O’Neill have to do with my story?” outburst while relaying McWilliams’ comments to Tevis Clyde Smith, which when coupled with the “He’s not accusing me of plagiarizing,” suggests that he “got” the reference.

To spend time with ‘Red Shadows” these days is also to resent the extent to which the character of Solomon Kane finds himself swaddled in frustration, frustration that has nothing to do with his God-fearingness. First, the damnable origin chimera: in “Red Shadows” Howard’s very first chapter-title, “The Coming of Solomon,” drops a reinforced-anvil hint that this is more than enough of an origin for the character; let conduct reveal conception. Which matters because the writer/director of the Solomon Kane film can’t bring himself to rely on Howard’s instincts; in an August 1, 2006 post to Conan.com, Michael Bassett wrote “I know this is going to annoy those among you who feel it’s unnecessary to ‘introduce’ Kane to a wider cinema-going audience, but I don’t think it’s okay to just drop into a character without understanding why he is who he is.”

Well, it used to be okay to do so; we pick up Sean Connery’s James Bond fully formed, busy being lucky in “love” and at cards shortly before he’s dispatched to investigate Doctor No, while the Man With No Name arrives in the wolf-eat-wolf border town of San Miguel from out of nowhere, and those were both fairly successful series. . .Leone cultists will recall that ABC apparently suffered from the same nervousness as Michael Bassett, and added a spurious prologue (directed by Monte Hellman) to the August 29, 1977 television premiere of A Fistful of Dollars: authority figure Harry Dean Stanton releases No Name from Federal durance vile for the express purpose of cleaning San Miguel up, or out. That jiggery-pokery of course undercuts the unforgettable scene two-thirds of the way through wherein the gringo gunslinger, having reunited Marisol with her family, responds to her “Why?” with a terse “Because I knew someone like you once, and there was no one there to help.” At that point in Eastwood’s career praise wasn’t exactly being slathered on his acting, but his delivery of that line is immaculate, a laconic almost-disclosure that has set fans to scripting their own backstories down through the decades. Howard provides statements or thoughts later in the Solomon Kane series that could be hauntingly effective onscreen in much the same way, did the screenwriter but trust the source material. Kane is not a superhero, and we don’t need to learn that he was bitten by a radioactive Puritan, or that Lin Carter’s iron-trimmed Bible fell on his head.*

(Origin-mania is often justified because a hero’s origin is what comes just before he sets out on his — wait for it — hero’s journey; were I Skynet, I would send Terminators back in time to kill not John Connor but another JC, Joseph Campbell)

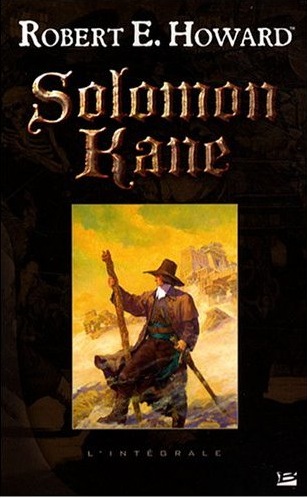

Perhaps even more frustrating than the obeisance to the Great God Origin is the fact that francophone Solomon Kane fans are now making out like Le Loup-style bandits:

Aventurier errant et vagabond sur la Terre, Solomon Kane traque et tue impitoyablement ses ennemis dans un monde élisabéthain pris de folie: brigands et pirates, certes, mais aussi vampires et morts-vivants. Instrument de Dieu ou puritain fou habite par des forces qui le dépassent, qui est Solomon Kane? L’une des créations les plus originales de Robert E. Howard. Cette édition, élaborée par Patrice Louinet, l’un des plus éminents spécialistes internationaux de Robert E. Howard et de son Å“uvre contient l’intégralité des aventures de Kane, reconstituées àpartir des manuscrits originaux, dans des traductions nouvelles et non censurées. Elle est de plus augmentée de nouvelles inédites, dont l’une paraît ici pour la première fois au monde.

Yep, Patrice has “remastered” The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane for its French edition; the book now includes a couple of drafts and the Malachi Grim “Blades of the Brotherhood,” plus “The Genesis of Solomon,” a back-of-the-book essay to match those he did for the Kull and Conan volumes.

Le Loup’s countrymen know how to honor his memory, but Del Rey is apparently in no hurry to make this bounteousness available to American readers. Merde; why did I learn German instead of la belle langue?

* Careless as a vagrant breeze, in his Imaginary Worlds Carter listed among Howard’s characters “a dour Puritan adventurer named Solomon Kane who brawled his way through the black jungles of Africa, battering down blood-soaked altars with a huge iron-bound Bible.” Does anyone remember a heavy metal Bible in the SK stories? The poor guy would have been woefully encumbered, what with the cat-headed juju staff he was already toting.