Glaurung and Smaug Make Room For Fafnir

Wednesday, January 7, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

In Surprised By Joy, C. S. Lewis recalled undergoing an epiphany upon reading the words “Balder the Beautiful/Is dead, is dead!” in one of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Norseified poems. “Uplifted into huge regions of northern sky, I desired with almost sickening intensity something never to be described (except that it is cold, spacious, severe, pale, and remote).” This morning Cimmerian Central has been similarly uplifted, thanks to Bookseller.com:

HarperCollins is to publish a new book by the late Lord of the Rings author J R R Tolkien. The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, edited and introduced by Tolkien’s son Christopher, will be published in hardback in May 2009.

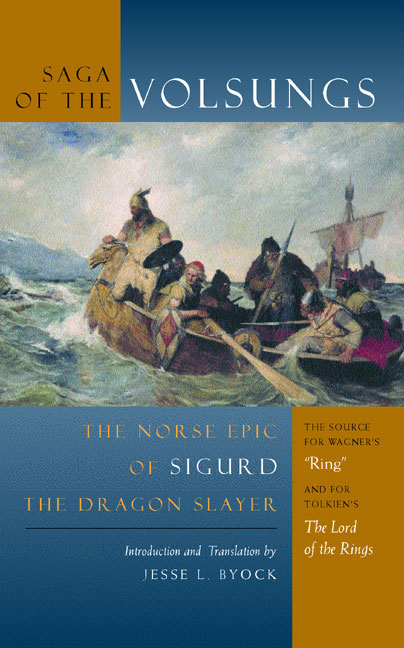

The previously unpublished work was written while Tolkien was professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University during the 1920s and ’30s, before he wrote The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The publication will make available for the first time Tolkien’s extensive retelling in English narrative verse of the epic Norse tales of Sigurd the Völsung and the Fall of the Niflungs.

Christopher Tolkien edited Tolkien’s most recent title The Children of Húrin in 2007.

Further details about the contents of the book will be revealed closer to publication.

As most of us have long since learned, no parade ever goes unrained-on and no metaphorical bag of Halloween candy is without its embedded razor blades and lacings of rat poison, so the appearance of this book will occasion the usual sneers about the impending publication of Tolkien’s grocery lists and a posthumous hyperactivity rivaling that of Tupac Shakur. But truly far-gone Tolkienists have known for many years that, like William Morris before him, he was captured early by what Morris deemed “the Great Story of the North, which should be to all our race what the Tale of Troy was to the Greeks,” and sought in his turn to capture something of that tale’s magic.

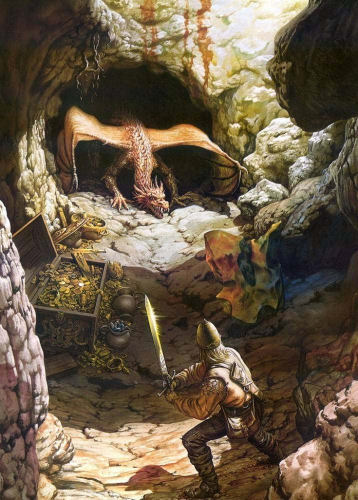

In “On Fairy-Stories” he recorded his boyhood passion for “the nameless North of Sigurd of the Völsungs, and the prince of all dragons.” Christina Scull and Wayne G. Hammond’s indispensable Reader’s Guide excerpts a writeup of a presentation on Norse sagas that he gave at his school (King Edward’s, in Birmingham) on February 17, 1911: In the “strange and glorious tale” of the Völsungs, the winning of “the red gold of Andvari, the dwarf” fails to brighten the life of Sigurd Fafnirsbane overmuch, for he “had no happiness from his love for Brynhild.” A few months before the guns of August began to have their say in 1914, Tolkien splurged on Morris’ The House of the Wolfings and 1870 Volsunga saga translation with some academic prize-money.

Hammond and Scull go on to note that “On 29 March 1967 he wrote to W. H. Auden, who had sent him part of the Elder Edda that he and Paul B. Taylor had translated into Modern English: ‘In return again I hope to send you…a thing I did many years ago when trying to learn the art of writing alliterative poetry: an attempt to unify the lays about the Völsungs from the Elder Edda, written in the old eight-line fornyrdislag stanza(Letters, p. 379).” Apparently this “attempt” amounts to 339 eight-line stanzas, and is companioned by “The New Lay of Gudrun,” 166 eight-line stanzas.

My own most cherished version of this material is likely to remain Rhinegold, because of Stephan Grundy’s fleshing-out of the fates of Sigmund, Signy, her hateful husband Siggeir, and the comparatively underexposed Sinfjotli — the strangest and cruelest part of the whole Volsunga saga, reeking of gore and the hot breath of the warg.

But the opportunity, for those of us who obsess along these lines, to compare Tolkien’s verse retelling to Morris’ 1876 The Story of Sigurd and the Fall of the Niblungs will be a fascination-fest (From Hammond and Scull we learn that in 1941 the professsor “delivered a lecture entitled William Morris: The Story of Sigurd and the Fall of the Nibelungs). Years before risking his own semi-novelistic-but-versified retelling, Morris introduced his saga-translation with a verse prologue:

O hearken, ye who speak the English Tongue,

How in a waste land ages long ago,

The very heart of the North bloomed into song

After long brooding o’er this tale of woe!

Hearken, and marvel how it might be so.

Now at last, after “long brooding” over the unavailability of Tolkien’s take on Sigurd and Gudrun (and, hint hint, his unfinished The Fall of Arthur), we’re in a position to “marvel how it might be so,” courtesy, yet again, of Christopher Tolkien — may his always-lucid longevity be that of an Aragorn! In terms of what Morris strove to render anew as “the courage that may not avail…the longing that may not attain…the love that shall never forget,” it doesn’t get much better than this.

Update: Posting in a theonering.net forum, Tolkienist Carl F. Hostetter reports “I found the work so stirring in a characteristically Tolkienian way that by the end it was all I could do to keep from jumping up, grabbing a sword, and killing some Huns.”