Bicentennial Bash at the Dank Tarn of Auber!

Sunday, January 18, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Monday, January 19, 2009 is the 200th birthday of America’s first-ever genre grandmaster, the writer described by Vincent Starrett as “a morose young man, stricken with poverty and genius.” Abraham Lincoln would follow Edgar Allan Poe into the world less than a month later (February 12, 1809), a fact that by 1860 must have had Poe draining several casks of Amontillado in the afterlife. And were his carry-me-back-to-old-Virginny spirit somehow to learn that he was sharing his special 2009 date with not only the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday but also the eve of Barack Obama’s inauguration — well, the kindest thing might be for him to ascribe the double affront to delirium tremens so severe as to continue bedevilling even ectoplasm.

Back in January of 1809, were his last several weeks in utero uncomfortably reminiscent of being buried alive for our feted and fated fetus? When Eliza Poe’s contractions bore down and became task-oriented, did he experience birth as a just-in-time rescue-by-exhumation? Yes, I’m turning Poe into a Poe character with such questions, but that’s been going on since his own lifetime. As Leslie Fiedler describes the syndrome in Love and Death in the American Novel

Yet Poe produced, after all, one completely achieved work of art in his writing career, a character who belonged specifically to none of his stories though he is, in part, the creation of all of them — a composite of Julius Rodman, Gordon Pym, William Wilson, Roderick Usher, and all the other pale, tormented failures at aggression, exploration, and love, who are haunted, buried alive, or clasped the arms of corpses. That character, who is, of course, Edgar Allan Poe. . .Poe not only wrote but lived.

“Poe is a skillful writer. It is skillful, marvelously constructed, and it is dead”: Hemingway’s takedown in The Green Hills of Africa is piquant because among the great American writers, he and he alone rivaled Poe in terms of collapsing the space between creator and creation (Frederick Frank, in his essay ‘The Gothic Romance,” begs leave to differ with the “dead” pronouncement, maintaining that throughout Poe, “Place becomes personality, as every corner and dark recess exudes a remorseless aliveness, and often a vile intelligence”.

Our birthday boy was born in Boston, seemingly well-positioned to write his way into what we often perceive as New England’s dark fantasy dynasty (Hawthorne, Lovecraft, Stephen King). In his 1991 Poe biography Kenneth Silverman notes that toddler Eddy’s inheritance when his (still-charming across two centuries) actress-mother died on December 8, 1811 was “a miniature portrait of Eliza, some of her letters, and her watercolor sketch of Boston harbor on the back of which she had written, “For my little son Edgar, who should ever love Boston, the place of his birth, and where his mother found her best, and most sympathetic friends.” Au contraire; Poe found, or convinced himself that he’d found, his worst, most antipathetic enemies there (as well as the Abolitionists he wanted to abolish), and would eventually take so many swipes at the region’s reigning poet it’s a miracle that worthy wasn’t reduced to being Henry Wadsworth Shortfellow. Dreaming of succeeding in, and seceding from, the starmaking apparatus of Boston, he became something of a one-man border state. Literary ambition pushed him north, while emotional allegiances pulled him south (as early in the antebellum chronology as 1835, he was already sorrowfully seated at the Mother of Presidents’ supposed sickbed: “The glory of the Ancient Dominion is in a fainting — is in a dying condition.”

H. P. Lovecraft put it quite mildly: “Poe’s fame has been subject to curious undulations.” Scott Peeples elaborates in The Afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe (2004): “To discuss Poe’s afterlife is really to discuss his afterlives, since he takes so many forms in literary criticism and other media.” As familiarity with the bloggers and their posts here at The Cimmerian‘s website confirms, Robert E. Howard is heading the same way. His afterlife has been tumultuous in a way that Fritz Leiber’s, for example, was never going to be; it could be argued that he’s required the nine afterlives of a spectral feline just to outlast the posthumous collaborations, piratings, and darkly valet-ed destinies that have come his way (I promise not to overdo the L. Sprague de Camp/Reverend Rufus Griswold analogies this time, but I would like to point out that at least the Rev. had tangled with the living Poe before he maliciously entangled himself with the dead Poe (who was not only a genius but a feudist of a vindictiveness that would spark a bidding war between Xotalancas and Tecuhltlis for his services).

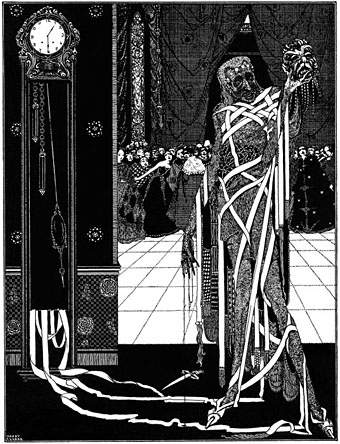

To commemorate some of those “curious undulations,” here are some of my favorite passages about what Daniel Hoffman, in Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe, termed our bicentenarian’s “strange, haunted, tawdry, inexorable, remote, yet inescapable Art.” If most visitors to this site enjoy even one or two of the selections, that works for me:

En 1846 ou 47, j’eus connaissance de quelques fragments d’Edgar

Poe; j’éprouvai une commotion singulière; ses œuvres complètes n’ayant été

rassemblées qu’après sa mort en une édition unique, j’eus la patience

de me lier avec des Américains vivant à Paris pour leur emprunter des

collections de journaux qui avaient été dirigés par Poe. Et alors je trouvai,

croyez-moi, si vous voulez, des poèmes et des nouvelles dont j’avais eu

la pensée, mais vague et confuse, mal ordonnée, et que Poe avait

su combiner et mener à la perfection. Telle fut l’origine de mon

enthousiasme et de ma longue patience.

Vous doutez que de si étonnants parallélismes géometriques puissent

se présenter dans la nature. Eh bien! on m’accuse, moi, d’imiter Edgar

Poe! Savez-vous pourquoi j’ai si patiemment traduit Poe? Parce qu’il me

ressemblait. La première fois que j’ai ouvert un livre de lui, j’ai vu, avec

épouvante et ravissement, non seulement des sujets rêvés par moi, mais des

phrasespensées par moi, et écrites par lui vingt ans auparavant.Charles Baudelaire, in a letter to Armand Fraisse on February 18, 1860

Poe had a pretty bitter doom. Doomed to seethe down his soul in a great continuous convulsion of disintegration, and doomed to register the process. And then doomed to be abused for it, when he had performed some of the bitterest tasks of human experience, that can be asked of a man.

D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature

His pretence to profound and obscure scholarship, his blundering ventures in stilted and laboured pseudo-humour, and his often vitriolic outbursts of critical prejudice must all be recognized and forgiven. Beyond and above them, and dwarfing them to insignificance, was a master’s vision of the terror that stalks about and within us, and the worm that writhes and slavers in the hideously close abyss. Penetrating to every festering horror in the gaily painted mockery called existence, and in the solemn masquerade called human thought and feelings that vision had power to project itself in blackly magical crystallizations and transmutations; till there bloomed in the sterile America of the ‘thirties and ‘forties such a moon-nourished garden of gorgeous poison fungi as not even the nether slope of Saturn might boast.

H. P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature (Will there ever appear a survey or study of this genre half as much fun to read as HPL’s? Thomas Ligotti, a fanbase turns its lonely eyes to you. . .)

In Poe’s life, the fiction of “social drinking” is given the lie; for to him, even the first drink was a plunge toward dissolution, a kind of symbolic suicide. He plays in the American mind the role of an anti-Rip Van Winkle, projecting the the fear that after the bust, one does not awake to a new and wifeless world, but continues to sleep the tormented sleep of the damned. If the figure of Poe in Baltimore refuses to be exorcised from the national imagination, it is because Poe’s terrible death befell him in a moment of typically American evasion; not only did he fall drunken beside a balloting place (and to be drunk on Election Day is surely the most American of acts!), but his drunkenness was prompted by a flight from women and marriage.

Leslie Fiedler, Love and Death in the American Novel

For many readers, Poe was the first distinctive literary voice. His themes as well as his rhythms, the inflections as much as the morbid imaginings, separated him from the rest of the scrivening herd. His tales entered our consciousness with a sepulchral flourish of trumpets, and, however wild or off-key, they captivated us.

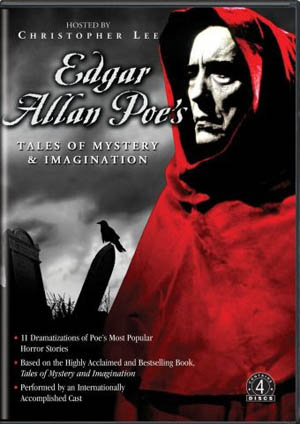

Arthur Krystal, The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (Case in point: Clive Barker, who in Clive Barker’s A-Z of Horror recalls, “One of the first books of fantastique fiction I purchased was Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, in a paperback edition with a lurid cover. It cost, if memory serves, 2/6d. I was ten or so and this seemed a fortune. But then treasure houses are seldom cheap. And I thought, “My God! There are adults out there who have the same kind of dreams that I have. This is marvelous!”

There isn’t anywhere you can go in this overcast, weedgrown, blood-fertilized field of ours that he hasn’t been first: the chilly blue-lit corners, the arena of onstage violence, Poet’s Corner, the comedy sideshow, the Vale of Things Man Was Not Meant to Know. In the perfumed, moldy halls of horror, he is the doorkeeper, the cartographer, and the resident ghost (Edgar, now be still: We swiped not from Walpole or Stoker with half so good a will).

John M. Ford, the Tales of Mystery and Imagination entry in Horror: 100 Best Books

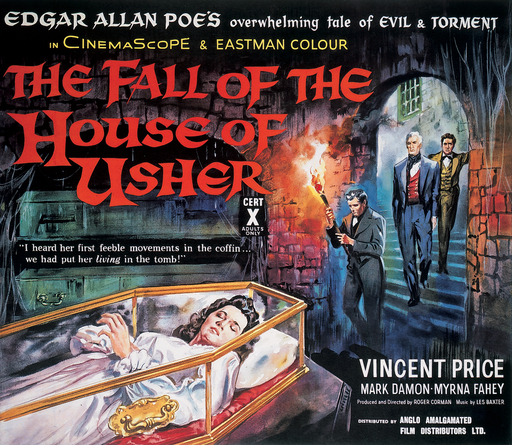

Poe also recognized that compression was a key element in producing the frisson of supernatural terror: in accordance with his strictures on the “unity of effect,” he understood that an emotion so fleeting as that of fear could be generated in short compass, and for a century or more his example compelled the great majority of literary supernaturalists to adhere to the short story as the preferred vehicle for the supernatural. Indeed, it could be said that “the Fall of the House of Usher” is a kind of rebuke to those countless British Gothicists who had dissipated the vital core of their supernatural conceptions by extending it over novel length; here, instead, was a “Gothic castle” every bit as terrifying as that of Otranto or Udolpho, but concentrated in a fraction of the space. Poe achieved this condensation by a particularly dense, frenetic prose style that could easily be mocked (and would in fact be mocked by such a fastidious writer as Henry James), but whose emotive power is difficult to gainsay.

S. T. Joshi, American Supernatural Tales (as always with Joshi, Stephen King;’s Overlook Hotel is implicitly scheduled for the wrecking-ball right along with the Otrantos and Udolphos of yore)

While “The Raven” is not explicitly about race, like Poe’s use of the orangutan in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” to commit “excessively outré” acts of violence against two white women, his idea of using a “non-reasoning [black] creature capable of speech” in writing “a poem that should suit at once the popular and the critical taste” (Works, 14:200, 196) evokes popular notions of blacks as parrots incapable of reason: its story of a dead white woman coming back in the form of an “ominous” black bird of prey who penetrates the heart and overtakes the mind and soul of the white speaker registers the simultaneous fear of and fascination with penetration, mixture, inversion, and reversal that emerges alongside of (and as part of) an increasingly aggressive nationalist insistence on sexual, social, and racial difference, white superiority, and Anglo-Saxon destiny. Perhaps better than other antebellum American writers, Poe reveals the linked processes of demonization, mixture, and reversal in the national imaginary. In “The Raven” as in other Poe poems and tales, the expelled other of American national destiny — the dark, the corporeal, the sexual, the female, the animal, the mortal — returns as an obsessive set of fantasies about subversion, amalgamation, and dark apocalypse.

Betsy Erkkila, “The Poetics of Whiteness,” in Romancing the Shadow: Poe and Race

If one is willing to overlook the irritating academic argot of substituting “imaginary” for “imagination,” Erkkila takes Toni Morrison‘s dictum that “No early American writer is more important to the concept of American Africanism than Poe” and runs with it, noting along the way the long and encrimsoned shadows cast by the Nat Turner rebellion and Haiti’s horrifically-won independence. Note how easily the last sentence could be repurposed for the Bride of Damballah — “In ‘Black Canaan’. . .the expelled other of American national destiny — the dark, the corporeal, the sexual, the female, the animal, the mortal — returns as an obsessive set of fantasies about subversion, amalgamation, and dark apocalypse.”

Or if readers prefer a more diverting approach to “The Raven”:

The Simpsons’ interpretation of “The Raven” (1990) with James Earl Jones has probably been watched by more people than any other adaptation of a Poe work, and yet some of its biggest fans are professors who relish, for instance, the post-modern humor of Homer-as-narrator reading a book entitled “Forgotten Lore.” One could argue that Matt Groening’s parodic treatment of the poem is appropriate to its almost comically overwrought style, (and yet it still scares Homer).

Scott Peeples, The Afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe

. . .a sort of prolonged mourning, an artistic brooding-on and assemblage of the fantasies activated by an ever-living past. As no product of his imagination would put to right what had gone wrong or restore what he once possessed, he would begin over and over, repeating in new forms, different imagery and fresh characters and scenes the dilemma which he presented in [Poems by Edgar A. Poe] as the peculiar condition of his existence:

I could not love except where Death

Was mingling his Beauty’s Breath —Kenneth Silverman, Edgar Allan Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (and again, how well that “artistic brooding-on and assemblage of the fantasies activated by an ever-living past” works for Howard, Lovecraft, and Tolkien as well as Poe)

To read Poe is to step on to another planet. There is no landscape like it.

Clive Barker, Clive Barker’s A-Z of Horror

“Poe has no truck with Indians or Nature. He makes no bones about Red Brothers and Wigwams,” D. H. Lawrence insisted, ignoring The Journal of Julius Rodman (Surprisingly, Poe characters fare better against grizzlies than against Madeline Usher) and “The Man Who Was Used Up.” Similarly, Leslie Fiedler claims “The West. . .was always for Poe only half real, a literary experience rather than a part of his life,” an un-hesperian orientation that makes a December 1933 riposte by REH to HPL all the funnier: “Edgar Allan Poe didn’t suffer want and die in poverty on the frontier. If he’d been there, somebody would have shot a deer for him, somebody would have showed him how to build his cabin, and helped him do it.” Who knows? Lovecraft surely choked on his canned goods when he read that, but Howard may have been on to something; venison might have been the nepenthe Poe craved. But where Charles Brockden Brown naturalized the Gothic in the New World with Wieland, Poe turned around and behaved as a squatter of sorts in “gloomy, gray hereditary halls” with Old Worldly, pre-democratic settings like the Hungary of “Metzengerstein,” the Toledo of “The Pit and the Pendulum,” and the “dim and decaying city by the Rhine” in “Ligeia,” leading the way for later provinces and possessions like Poictesme, Joiry, Averoigne, Aquilonia, perhaps even Westeros.

From an aesthetic point of view, it would be nice to be able to amend Howard’s assertion by way of his character Conrad in “The Children of the Night” that “the three master horror-tales” are “Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher, Machen’s Black Seal, and Lovecraft’s Call of Cthulhu,” swapping “The White People” for The Novel of the Black Seal (despite the latter’s Worm-farm significance) and maybe even “The Colour Out of Space” for “The Call of Cthulhu.” But the creator of Blassenville Manor knew an ill-omened edifice when he saw one, even if the Southernness of Poe’s Southern Gothic was not-so-readily apparent. The House of Usher falls because that’s what Poe built it to do, not because Sherman’s incendiaries are marching through Georgia.

Poe and Howard were both not-quite-Southerners, and both, it seems to me, conflicted about the peculiar institution and the peculiar rationalizations and extenuations it demanded. “I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe, Ralph Ellison’s narrator announces in Invisible Man. Black is often more than just black and dark, more than just dark in Poe stories, and although Richard Kopley has identified a sensational 1838 news story about an African-American who razored his wife, a story that was juxtaposed to a reference to “a hideous Negro with an orang-outang face,” Joan Dayan for her part sees “Hop-Frog,” at the big finish of which the abusive king and his seven ministers dangle “in their chains, a fetid, blackened, hideous, and indistinguishable mass,” as “revenge for the national sin of slavery” (Between the orang of “Murders” and the Dr. Zaius costumes of “Hop-Frog,” Poe certainly had dibs on that branch of the family Pongidae).

One last thing about Poe-‘n’-Howard; namely, my favorite instance of their two great tastes tasting great together. We’re talking the transition from Chapter I to Chapter II of “Kings of the Night”; the just-summoned Kull looms legendarily “against the golden birth of day.” And then we get this

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule —

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of Space — out of Time.

Does Howard’s fascination with gunfighters help to explain his ability to drill his readers between the eyes with just the right epigraph? Those lines, from Poe’s “Dream-Land,” stop me dead in a good way every time. We know from a couple of Howard’s letters that he worried about “Kings of the Night” being insufficiently weird-wired; in effect, the poem and the Bran Mak Morn story reinforce each other. This is what posthumous collaboration should be like: Kull is “played onstage” with a Fanfare for the Uncommon Man composed by America’s most penumbral poet.

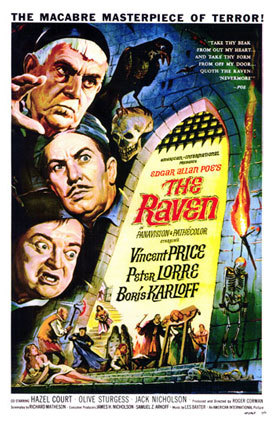

Scott Peeples writes “Strictly as an icon, Poe is a marketer’s dream, especially after Lugosi and Price: his name, even his face, simultaneously signifies the thrill of a campfire ghost story and the erudition of great literature.” In his “Lionizing: Poe as Cultural Signifier” chapter, Peeples mentions items like “Manly Wade Wellman’s ‘When it Was Moonlight’ (published in the fantasy magazine Unknown in 1940); Poe investigates a case of premature burial only to discover — and vanquish — a female vampire,” or “Michael Avallone’s ‘the Man Who Thought He Was Poe” (Tales of the Frightened, 1957), [which] features a Poe aficionado who plots his wife’s murder only to be tricked by her and entombed in a refrigerator.” To which I can add Robert R. McCammon’s 1984 novel Usher’s Passing, which tries really hard but is ultimately little more than a remora affixed to Poe’s Megalodon. Far, far better, in fact an homage that doubles as a tour de force, is Dan Simmons’ setpiece in The Terror (2007) wherein the icebound Northwest Passage-seekers of the Franklin Expedition (1845-1848) throw a Winter Carnival with a “Masque of the Red Death” theme (the story’s first publication has been circulating among the Expedition members). Their re-creation is doing Prince Prospero proud when something very old and very cold invites itself to the party.

Musically, matters could only improve after the Alan Parsons Project’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1976), and they did with Lou Reed’s The Raven (2003), spun off from his POEtry collaboration with Robert Wilson, and Closed on Account of Rabies, a 1997 double CD upon which Gabriel Byrne, Jeff Buckley, and Marianne Faithfull read Poe unabridgedly to impeccable accompaniments. Suffice it to say that for Christopher Walken, who’s always seemed like he was born on the Night’s Plutonian shore, “The Raven” is clearly a homecoming.

Poe isn’t all Halloween candy; Herman Melville confessed “Dollars damn me,” and dollars and dolors both damn Poe at times. In addition, what HPL said of REH –“Humour was not a specialty” — was infinitely more true of the earlier writer. And then there’s his habit of over-ostentatiously exhibiting bits of learning like heirlooms rescued after an earthquake or salvaged from a shipwreck. But in fairness, most of us remember Howard’s 1928 reference to “the school to which Poe contributed and I at present honor with my presence” — well, to the earlier fantasist, that school must have seemed like it had no headmaster and a classroom with only one desk and a blank blackboard. He hand-crafted a tradition, a precedent, an exemplar. Someone had to go first, pay the price and catch the flak, both in life and in afterlife. Poe walked point; if Hammett, Chandler, and Lovecraft are now secured and sinecured in the Library of America, with Howard reportedly on his way, it’s because Poe held the door open for them.

In his introduction to Shapes that Haunt the Dusk, a 1907 proto-paranormal anthology, the novelist William Dean Howells observed that the partiality of Americans to supernatural stories “is their common inheritance from no particular ancestry.” No particular ancestry, save Poe, who died childless but went on to sire Lovecraft; a sentence near the end of “Ms. Found In a Bottle” now reads like premonition as pastiche: “It is evident that we are hurrying onward to some exciting knowledge — some never-to-be-imparted secret whose attainment is destruction.” Lovecraft, and also Ray Bradbury, Shirley Jackson, Robert Bloch, Richard Matheson, Thomas Ligotti — this status as paterfamilias is emphasized by two books with the title Poe’s Children, Peter Straub’s 2008 anthology (stories by “breathtaking ‘literary’ writers who in this newly liberated atmosphere have no problem embracing their inner Poe” and, a decade earlier, Tony Magistrale and Sidney Poger’s nonfiction Poe’s Children: Connections between Tales of Terror and Detection.

Despite Poe’s exertions as an architect of, and supplicant in, a temple of Thanatos in an otherwise monotonously monotheistic era, despite the charnel cologne and phobia about premature entombment, despite those stints in a pauper’s grave and pantheon-purgatory, few artists have ever been less dead 200 years after they were born. Happy Birthday, and may the champagne in the “ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir” flow freely.

MARK ADDS: An excellent collection of observations and artwork, Steve. Appropriately, my father-in-law (a Robert E. Howard fan prior to my meeting him), by way of explaining to people who, on occasion, would ask who Robert E. Howard was, would reply, “He’s the Edgar Allen Poe of Texas.” Nice and succinct. I wish I’d thought of that one.