An Early, Albeit Pagan, Christmas in the Old North

Monday, December 15, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

During the weapon’s dark nativity the clangor of coerced swordsmith-toil masked the muttering of murder-curses:

Sigrlami was the name of a king who ruled over Gardaríki; his daughter was Eyfura, most beautiful of all women. This king had obtained from dwarfs the sword called Tyrfing, the keenest of all blades; every time it was drawn a light shone from it like a ray of the sun. It could never be held unsheathed without being the death of a man, and it had always to be sheathed with blood still warm upon it. There was no living thing, neither man nor beast, that could live to see another day if it were wounded by Tyrfing, whether the wound were big or little; never had it failed in a stroke or been stayed before it plunged into the earth, and the man who bore it in battle would always be victorious, if blows were struck with it. This sword is renowned in all the ancient tales.

That’s the introduction of Tyrfing in Saga Heidreks Konungs ins Vitra, The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise, translated, introduced, annotated, and backstopped with appendices by none other than Christopher Tolkien back in 1960, when he was a Lecturer in Old English at Oxford’s New College. Nor is this ominous glaive’s renown limited to ancient tales; let’s join Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword already in progress, as the eyeless, dragonskin-aproned Jötun-smith Bolverk is tasked to reforge “the banes of heroes,” which has been snapped in two by Thor himself:

Bolverk’s hands fumbled over the pieces. “Aye, ” he breathed,” Well I remember this blade. Me it was whose help Dyrin and Dvalin besought, when they must make such a sword as this to ransom themselves from Svafrlami but would also have it be their revenge on him. We forged ice and death and storm into it, mighty runes and spells, a living will to harm.” He grinned. “Many warriors have owned this sword, because it brings victory. Naught is there on which it does not bite, nor does it ever grow dull of edge. Venom is in the steel, and wounds it gives cannot be healed by leechcraft or magic or prayer. Yet this is the curse on it: that every time it is drawn it must drink blood, and in the end, somehow, it will be the bane of him who wields it.”

The weapon’s “hell-blue” flare and “hawk-scream” dominate the rest of the novel, with Odin Ill-wreaker himself placing its comeback in a wider context:

“Tyrfing still gleams on the chessboard of the world. Thor broke it lest it strike at the roots of Yggdrasil; then I brought it back and gave it to Skafloc because Bolverk, who alone could make it whole again, would never have done so for As or elf. The sword was needed to drive back the trolls — whom Utgard-Loki had been secretly helping — lest Alfheim be overrun by a folk who are friendly to the foemen of the gods. But Skafloc cannot be let keep the sword, for that which is in it will make him seek to wipe out the trolls altogether, and this the Jötuns dare not allow, so they would move in, and the gods would have to move against them, and the doom of the world be at hand.”

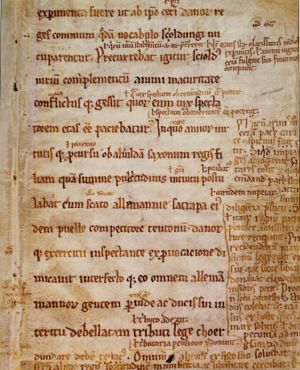

The never-mass-marketed 1960 hardcover King Heidrek, stalked by Tolkienists for decades, has only been obtainable at prices to which being blood-eagled would be preferable. But last week Jason Fisher’s Lingwë — Musings of a Fish, a blog especially and rewardingly concerned with the “inside language” aspect of JRRT, tipped us off that The Viking Society for Northern Research has in effect thrown open its doors to the general public by offering many past publications as free-of-charge PDFs. Redefining unseemly haste, I’ve been downloading up a storm ever since, beginning with Heidrek-via-Christopher Tolkien but continuing on to scholarly swag like Haraldr the Hard-Ruler and His Poets, Wagner and the Volsungs, Skaldic Verse and Anglo-Saxon History, “A Most Vile People”: Early English Historians and the Vikings, and the promisingly-titled The Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-Tongue.

As sagas go King Heidrek, also and often known as Hervarar saga, is not one of the more realistic, even legalistic, accounts of squabbles between neighbors and small-claims-court-wrangling, but, like Völsunga saga, an example of the fornaldarsogur, the tales of ancientry and the hero-harrying workings of wyrd.

Fair warning: frustration is part of the package deal here; the sagas do not always tell, or tell all of, the stories we latecomers most want told. Coherence and consistency are as alien to this world as would be conflict resolution seminars. As the younger Tolkien stresses, “‘Legends’ of the past can only exist for us in written works of art that come from the minds of men who felt themselves quite at liberty to change the stories they inherited, to identify this personage with that, and in the course of time to produce such a nexus as no one can hope to unpick.” He also cautions, “One must not think in terms of a great mythological atlas of the northern world, with legendary lines of latitude and longitude.” Indeed the factual fluidity and wayward narrative lead him to concede that this saga is “something of a gallimaufrey, unkempt, ununified, with many inconsistencies…the saga-writer would have needed to be far more ruthless with his material than he was to make a satisfactory design.” What one yearns for, of course, is a learned-but-ruthless novelist to do what Poul Anderson did with Hrólf’s Saga Kraka in 1973 and Stephan Grundy did with the Walsing/Nibelung story-cluster in 1994.

Here and there we encounter the quiet but quite effective wit that irrigated some comparatively desiccated chapters of The History of Middle-earth: “The demands of alliteration and accuracy together have meant pressing into service a few words that some may think should be allowed to die in peace, even in translating heroic poetry.” And although we need not rank the Tolkiens with Philip and Alexander of Macedon as examples of genius being passed down patrilineally, a few passages suggest that Christopher might have done quite well out on his own rather than as a junior partner in the “family business” had he not loyally concentrated on executorship of his father’s literary estate. His Appendix B, which deals with the outsized character Gudmund of Glasisvellir (Guthmundus in Saxo Grammaticus’ Gesta Danorum) is a dark fantasy banquet:

They came to a ‘gloomy, neglected town, looking more like a cloud exhaling vapour,’ a dark fortress with the heads of dead warriors impaled on the battlements, and savage dogs guarding the entrances. The conception of the halls of Geruthus is a grim one, and it has power even in Saxo’s swollen language: a picture of great riches amid hideous decay, almost as it were a great burial-ground, with gems and horns and golden vessels on a floor of snakes and dung, beneath a roof of spearheads and everywhere a vile oppressive stench. ‘Bloodless phantasmal monsters’ armed with clubs were yelling, others played a gruesome game with a goat’s skin which they tossed back and forth. At last they came upon Geruthus himself, an old man seated upon the high seat with his body pierced through, and beside him three women with their backs broken.

To become a Howardist is often to submit to capture by “the Northern thing”; I count works by Gwyn Jones — The Norse Atlantic Saga (1964), A History of the Vikings (1968)–, Eric Linklater —The Ultimate Viking (1955), The Conquest of England (1966) –, and Hilda R. Ellis-Davidson — The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England (1962), Gods and Myths of Northern Europe (1964), The Viking Road to Byzantium (1976), and The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe (1993) — as fair-haired rather than fairweather friends. But to read something actually handed down by those who had at least one foot planted in the pertinent culture even if they also nervously touched their crucifixes for reassurance is much more of a frisson-fest, as with The Waking of Angantyr, one of the first Old Norse poems to lead an afterlife upon being translated into English.

Its leading lady Hervör is too powerful for empowerment to be an issue and might well cow the Brunhild of Howard’s “the Gods of Bal-Sagoth”: “She did more often harm than good, and when it was forbidden her she ran away to the woods and killed men for her gain.” Calling herself Hervard and leading a viking’s life, she dares the haunted island of Sàmsey for a fraught encounter at the “barrow of the berserks” (her father Angantyr and his brothers, all of whom were slain there). She demands Tyrfing, “the hater of mailcoats,” and is undeterred as “Hel’s gate is lifted/Howes are opening.” “No blaze can you light,/burning in darkness,/that your funeral fires/should with fear daunt me,” she assures her father, who reluctantly turns over “the doom-bringer.” Of her prize she unwisely says “I count it dearer than were all Norway beneath my hand.” No way that ends well; as Christopher Tolkien comments the whole sequence “expresses with extraordinary force the fear and mystery of the grim dead lying lifeless but sometimes wakeful in their burial mounds.”

Her son Heidrek is an exemplar of what Dean A. Miller’s The Epic Hero (2000) describes as “the ambiguously marked career, with the dramatic mixture of good and ill, of one all too close to a god whose attention and gifts are not at all safe for any man to boast of, be he hero or not,” and a bad actor even by saga-standards:

When Heidrek had walked from the buildings for a short time, it came into his heart that he had not yet done enough harm, and turning back towards the hall he took up a great stone and hurled it in the direction from which he heard men talking together in the darkness.

After securing a crown much bloodier than that with which Conan was fitted by Del Rey Books, Heidrek eventually finds himself on the receiving end of a riddle-me-this contest with Odin, who is passing himself off as one Gestumblindi. Christopher Tolkien notes of the ensuing asking-and-answering “There are no [other riddles] in ancient Norse; and even more surprisingly, there is no record in the poetry or the sagas of a riddle ever having been asked.” Of course one instamatically thinks of the senior Tolkien, Gollum and Bilbo riddling in the dark at the roots of the Misty Mountains. The particpants part just as badly here, with Heidrek going so far as to swing at Odin with Tyrfing. “That you have attacked me, and would slay me without offence,” the god retorts,”the basest slaves shall be the death of you.”

And so they are, nine of them, not baseborn but basely behaved. The violence of this saga usually happens within the space of a single sentence, declarative but never declamatory: “But of the grim game between Hjàlmar and his foe, there is this to tell, that Hjàlmar got sixteen wounds, but Angantyr fell dead.” Such terseness, although never giving away too much, occasionally asks too much of the modern reader, as when Sifka, daughter of the king of the Huns, has become an encumbrance for Heidrek even before he lugs her across a river:

There was nothing else for it but to cast her down from his shoulders and break her backbone, and so he left her drifting away dead down the stream.

Styrbjörn the Strong, Starkad Áludred, who attacks “with four swords at once,” Hélgrim Halftroll, Heidrek Wolfskin, Ívar the Wide-grasping, and Harald War-tooth all poke their bristling heads in (At least one of those worthies has to be a James Allison incarnation).

Evenly matched foemen “show each other the way to Valhöll,” and we hear tell of hauga-eldrinn, “the fire that burns over treasure hidden in burial-mounds.” Embracing his fast-approaching death, a warrior observes “The carrion birds fly from the south; this is the last meal I shall set for them.” A few roughhewn epigrams deserve their own T-shirts:

“It becomes not ghosts costly arms to bear.”

“Ale overmasters many a warrior.”

“When great men ask questions about dung-beetles, they have talked too long.”

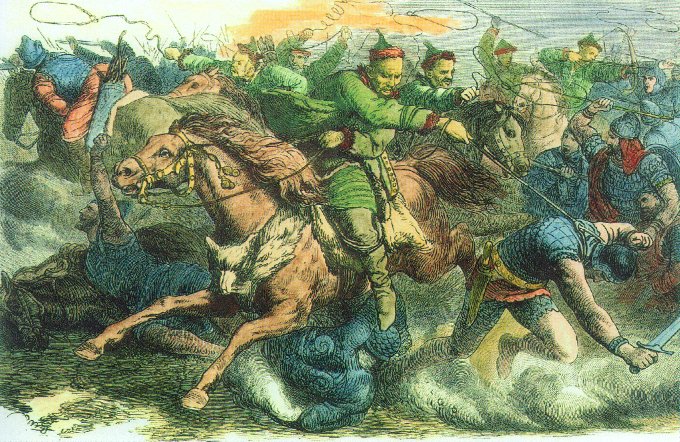

In only one choice would I dare to second-guess Christopher Tolkien’s translation: his use of the term “phalanx” for Hun-formations is just too much of a distraction (Are the Huns toting sarissas?) Those units enter the story in a startlingly cinematic passage as another Hervör, granddaughter of the first, spots death en route from afar:

One morning at sunrise Hervör stood on a watchtower above the fortress-gate, and she saw a great cloud of dust from horses’ hooves rising southwards towards the forest, which for a long time hid the sun. Presently, she saw a glittering beneath the dustcloud, as though she were gazing on a mass of gold, bright shields overlaid with gold, gilded helms and bright corslets; and then she saw that it was the army of the Huns, and a mighty host.

That’s from The Battle of the Goths and Huns section of the Hervarar saga, which regrettably has come down to us as a text corrupt beyond even the ability of Patrick Fitzgerald to indict. In Christopher Tolkien’s words “an academic battlefield for more than a century,” the story just about succeeds anyway as a narrative of the war that breaks out when Heidrek’s sons (one of whom, Hlöd, has been reared at the court of the steppe-lords) are unable to agree on a division of their patrimony: “Fire in the marches of Mirkwood is raging/With the gore of men all Gothland’s sprinkled!” Mirkwood is just one of the Tolkien-tripwires, and anyone familiar with William Morris’ The Roots of the Mountains (1890) will feel right at home upon reading “But the Goths were defending their freedom and the land of their birth against the Huns, and for this they stood firm, and each man urged on his comrade.”

But the real thrill of The Battle of the Goths and Huns reaches us from an age long before Tolkien, Morris, or even the Icelanders who composed or compiled the sagas. A thousand years before the colonization of that Ultima Thule, the Völkerwanderungen of the Goths were only just beginning, and like Hervör in her watchtower, even from this distance we can glimpse a legendary-but-also-historical gleam through the obscuring dust. The Dnieper flows through the story, the name Tyrfing is related to Tervingi, a designation the Romans applied to the Visigoths, and CT points out, “Harvaóa is the same name in origin as ‘Carpathians.’ Since this name in its Germanic form is found nowhere else at all, and must be a relic of extremely ancient tradition, one can hardly conclude otherwise than that [the reference is] a fragment of a lost poem (presumably on the subject of Heidrek’s death and Angantyr’s revenge for him) that preserves names at least going back to poetry sung in the halls of the Germanic peoples in central or south-eastern Europe.” Whether in the work of REH and JRRT or here, depth always trumps length.

As Dean A. Miller puts it, swords of an “Odinnic” persuasion are “likely to be aligned with alterity.” Sometimes they’re moundswords that have sojourned “deep in death’s shadowy realm,” and in modern fantasy they’re often Not From Around Here:

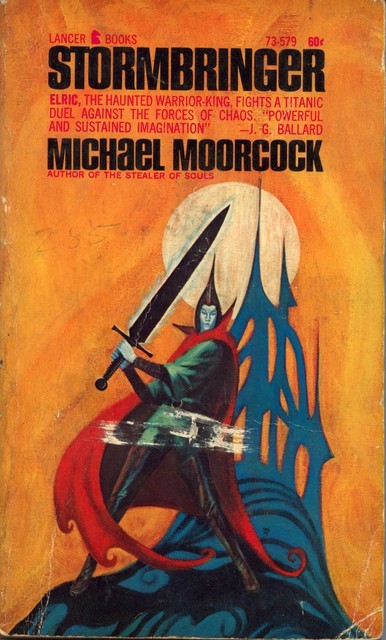

Moorcock’s runesword beat all versions of Tolkien’s The Children of Húrin into print; it turns out that the story of Kullervo in The Kalevala hit both authors in boyhood like a bolide. JRRT’s black blade debuts when Beleg Strongbow admits that he can no longer trust in his archery alone and asks Thingol Greycloak for “a sword of worth”:

Then Beleg chose Anglachel; and that was a sword of great fame, and it was so named because it was made of iron that fell from heaven as a blazing star; it would cleave all earth-dolven iron.

Anglachel is a product of the smithy of Eöl the Dark Elf, one of the most sinister characters in The Silmarillion other than servants of Morgoth. Thingol’s queen, the semi-divine Melian, is moved to remark “there is malice in the sword. The heart of the smith still dwells in it, and that heart was dark. It will not love the hand that it serves; neither will it abide with you long.” She’s right about that, and the sword goes on to greater infamy as Gurthang, the “iron of death,” because of which Túrin becomes known as the Blacksword, until the weapon even plays a cold-voiced speaking part at the end of his story.

Moorcock and Tolkien’s talking swords are true to their creators; Stormbringer relativizes Elric’s crimes — “Farewell, friend. I was a thousand times more evil than thou” — whereas Gurthang holds Túrin accountable for his bodycount of friends-and-civilians before promising “I will slay thee swiftly.” Both blades address their “masters” intimately: thou, thee.

Is it not a disturbing conceit that broadsword or battle-axe, means toward the end of obliterating life and personhood, might themselves quicken, acquire the attributes of living things? For all the death-dealing in the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Aeneid, I can’t remember a single instance of what Dean A. Miller calls the “named” or “fated” weapon; Achilles’ replacement-armor is a big deal, but lacks agency or its own agenda. Miller mentions a suggestion that “only after the development of the so-called damascened …sword blade, probably in the sixth or seventh century, did this weapon achieve its exceptional yet conventional place” as the hero’s “nearly ubiquitous partner,” leading to the northern European “icon and symbol” of the sword as

…central, dominant — and even alive. The brilliant translator of the Nibelungenlied, A. T. Hatto, included the sword Balmung in his glossary of the characters’ names — because, he says plainly, “in heroic poetry swords are persons.”

Miller goes on to list “a whole armory of ‘named’ weapons”: Grettir the Strong’s Aetartangi, Egill Skallargrimsson’s Adder and Dragvendil, Geirmundr the Noisy’s Leg-biter, Grayflank from Gisla saga , Bodvar Bjarki’s Laufr and Svirtir, Thorkell Eyjolfsson’s Skofnung, Bersi’s Hviting. It interests me that Robert E. Howard never wanted any part of this tradition. He was aware of some of it, whether by way of his own saga-delvings or as filtered through Richard Wagner: “The Lion of Tiberias” offers that wonderful description of John Norwald’s “blue eyes cold and hard as the blue steel whereof Rhineland gnomes forge swords for heroes in northern forests.” But edged weapons remain mostly anonymous and anodyne in his heroic fantasy (we never even hear tell of Kull and Conan’s swords of state) which is why de Camp and Carter’s “The Thing in the Crypt” struck such a false, Thongorian note. Perhaps as a child of the Machine Age Howard felt that a monickered sword was as silly as naming one’s .45 automatic or .38 revolver.

Tyrfing also shows up in John Myers Myers’ Silverlock (1949)and went on to star in Bernard King’s novels drawing on the stories of the hero-villain Starkad/Starkadder in Gesta Danorum and Gautreks saga): Starkadder (1985), Vargr-Moon (1986), and Death-blinder (1988).

And blade-brethren abound, as in Andrew Offutt’s 3 novels about Jarik Blacksword, The Iron Lords (1979), Shadows Out of Hell (1980), and The Lady of the Snowmist (1983). Superhuman willpower was required for Druss the Legend to rule by, rather than be ruled by, the Elder axe Snaga, the Sender, while Skilgannon the Damned was blessed/burdened with the Swords of Night and Day. Subsequent avatars the Shade Blade, Blackrazor, Soul Reaver, Frostmourne, Ashbringer, Doombringer, Terry Pratchett’s long-winded Kring, Hairsplitter, Hedgetrimmer, Backbiter, and Mellowharsher (a few of those might be Tompkins inventions). Dragnipur, the dark blade of Steven Erikson’s lordly, dracomorphic Anomander Rake, doubles as a holding-pen for the souls of its victims:

The sentient sword can be overdone, as no one knows better than Michael Moorcock, whose Stormbringer has been borrowed more often than money. A case can be made that “The Stone Thing,” most recently available in Elric: To Rescue Tanelorn, should have been the last word:

Out of the dark places; out of the howling mists; out of the lands without sun; out of Ghonorea came tall Catharz, with the moody sword Oakslayer in his right hand, the cursed spear Bloodlicker in his left hand, the evil bow Deathsinger on his back together with his quiver of fearful rune-fletched arrows, Heartseeker, Goregreedy, Soulsnatcher, Orphanmaker, Eyeblinder, Sorrowsower, Beanslicer, and several others.

But Tyrfing was crafted by Dyrin and Dvalin to be impervious to such mockery. One of the more haunting cameos notched by the sword is in William Morris’ poem “In Arthur’s House.” During a deer hunt, Arthur, Guinevere, Gawain, and Lancelot meet and converse with “a man exceeding old,” who brings a touch of boreal frost to Camelot’s sunwashed midsummer. The court-folk admire the venerable blade he displays to them:

But grimly smiled the ancient man:

“E’en as the sun arising wan

In the black sky when Heimdall’s horn

Screams out and the last day is born,

This blade to eyes of men shall be

On that dread day I shall not see –”

Fierce was his old face for a while:

But once again he ‘gan to smile

And took the Queen’s slim lily hand

And set it on the deadly brand

Then laughed and said: “Hold this, O Queen,

Thine hand is where God’s hands have been,

For this is Tyrfing: who knows when

His blade was forged? Belike ere men

Had dwelling on the middle-earth.

At least a man’s life is it worth

To draw it out once: so behold

These peace-strings wrought of pearl and gold

The scabbard to the cross that bind

Lest a rash hand and heart made blind

Should draw it forth unwittingly.”Blithe laughed King Arthur: “Sir,” said he,

“We well may deem in days by gone

This sword, the blade of such an one

As thou hast been, would seldom slide

Back to its sheath unsatisfied.

Lo now how fair a feast thy kin

Have dight for us and might we win

Some tale of thee in Tyrfing’s praise,

Some deed he wrought in greener days,

This were a blithesome hour indeed.”

This was enough to set me to dreaming of a crossover, in which Tyrfing finds its way to court and into the eager hands of Mordred, so that it can ultimately duel with Excalibur and deal Arthur his death-wound at Camlann.

Despite his occasional fallibility with regard to Robert E. Howard, and his near-lifelong wrongheadedness about J. R. R. Tolkien, Michael Moorcock is an extemely perceptive writer, and I don’t believe he’s ever said anything more insightful than this:

To this day I advise people who want to write fantastic fiction for a living to stop reading generic fantasy and to go back to the roots of the genre as deeply as possible, the way anyone might who takes his craft seriously. One avoids becoming a Tolkien clone precisely by returning to the same roots that inspired The Lord of the Rings.

I know thoughtful people who are convinced that “the Northern thing” has been done to death in popular culture. With the best of intentions they urge the fantasy genre, on the page and on the screen, to turn to other climes and other cultures, retiring a stripmined, ransacked iconography wherein the very aurora borealis might now seem as tawdry and insincere as a neon come-on. Christopher Tolkien’s presentation of The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise is not only a fascinating foreshadowing of The History of Middle-earth but a reminder that no matter how many meretricious and mercenary versions of the Ancient North’s mythology have been in our face, for many of us those gods and heroes and dooms, to the extent that the original texts preserve them, are also in our blood.